|

(Ed. Note: I originally intended to do a formal interview with Joe and Kevin, but as the day progressed and the friendly vibe between us grew, I became less and less interested in the idea of shifting gears into being “on the record”. So I kept it casual. As a result, this article is a narrative and not in a traditional interview format.)

Back in 2012, when I first caught the jazz record collecting bug, I quickly took a strong interest in recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who recorded for numerous classic jazz labels including Blue Note Records. I had a background as an amateur audio engineer so I was also interested in his methods. On one occasion, I reached out to mastering engineer Kevin Gray, who had been working with Rudy’s original master tapes for several years in conjunction with various jazz reissue labels including Music Matters.

Kevin was very polite and helpful, so a few years later when I published an article on groove wear, I thought it would be a good idea to ask Kevin to proofread it before it was published. After he read it, he wanted to talk to me over the phone, so that was the first time we spoke.

On a few occasions I would ask him questions about my research so we stayed in touch. Then last November when I launched RVG Legacy, a website dedicated to preserving the legacy of Rudy Van Gelder, I let him know about it. It must have flown under his radar until this summer when he emailed me excited about what I had put together. A couple weeks later he emailed me again, saying he had been talking to Blue Note reissue producer Joe Harley about my Rudy site, and they decided to invite me to a Blue Note remastering session at Kevin’s mastering studio, Cohearent Audio in Los Angeles.

I was beaming with excitement. For the first time I would get to hear Rudy Van Gelder’s original master tapes in person, someone whose methods and sound I had been carefully studying for the past ten years. So I booked a flight and waited patiently for the day to come where I packed my bags and headed for the West Coast.

|

| Rudy Van Gelder in his Englewood Cliffs studio in 1962 (Photo credit: Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images LLC) |

An Unexpected Listening Exercise (and Outcome)

The first morning I was in SoCal, my co-pilot, Tarik, and myself began the 90-minute drive west from San Bernardino at 8 A.M., headed for Cohearent. Upon pulling up to the address, Tarik and I were met with the unassuming façade of a small, single-floor, seafoam green house. We had been instructed to go through the gate to the building on the back of the property.

|

| World-class mastering incognito: View of the Cohearent Audio property from the street |

Once inside, it wasn’t long before Kevin hit “play” on one of his Studer reel-to-reel tape recorders. While we waited for Joe to arrive, the sound of music began flowing from Kevin’s massive custom-built speakers at the front of the room, each of which consists of two subwoofers with sealed enclosures, two woofers, one midrange driver and one tweeter.

Before I tell you what happened next, I think it’s only fair that I preface it with a comment about what kind of listener I am. I am a very honest listener. I don’t pull any punches. For example, if it costs ten times as much and sounds the same to me, I’m going to be honest about that.

When Kevin played that first tape, it literally made me tear up. (I wish I could tell you what it was. All I can say is that it was a recording made by a well-known yet underrated West Coast jazz recording engineer in 1958.) I had a strong emotional response that was completely unexpected. If I had to describe what it was that made it sound so special, I’d guess that it was a combination of lifelike dynamics and a very natural stereo soundstage. I know this may sound cliché, but in a word, it was haunting.

Keep in mind that my experience cannot be attributed to the tape alone. Of course, Kevin’s playback system and room also played an important role. After talking to Kevin a little about his background, it became clear that he is a master of electrical engineering and acoustics, and the evidence is in the spectacular playback achieved in his studio, which he designed and built himself, bass traps, electrical wiring and all.

The second thing Kevin played for us was a tape of a Rudy Van Gelder recording dating back to 1961. Time for another preface…

I adore Rudy Van Gelder. His story of creative and entrepreneurial independence has inspired the way I work and live for many years now, going all the way back to 2004 when I first read the book Temples of Sound. Being someone who has always firmly believed that audio recording is an artistic medium that should not necessarily be used in a way that attempts to imitate life as closely and objectively as possible, I have always appreciated the unique character of his recordings. I have stuck up for Rudy in internet chat rooms when he was getting trashed by audiophiles claiming to be “in the know” about other great jazz engineers like Roy DuNann and Fred Plaut.

That said, when the Rudy tape came on, I did not feel as “wowed”. And I think the most important factor here was my feelings — how the sound and the music made me feel. In comparison, Rudy’s tape sounded a little “hyped up”. The top end was much more present, and the sound was less relaxed. What this ultimately amounted to, I feel, is that where the first recording sounded chillingly like the musicians were in the room with us (I have listened to expensive home audio systems before and never got this feeling), the Rudy recording sounded like a recording — an outstanding, gorgeous recording, but nonetheless a recording. And maybe that makes sense since Rudy never claimed to try to make his records sound “as realistic as possible”.

It’s also possible that I came to the studio that day with my own prejudice, that I subconsciously was setting a bar in my mind for “realism in playback”. Most jazz collectors and audiophiles will agree that the greatest classic jazz recordings are the ones that sound the most realistic. I also feel it’s important to keep in mind that Joe Harley has on more than one occasion explained that his goal as a remastering engineer is to make his reissues sound as close as possible to the experience of being in the room with the musicians themselves. In light of this, perhaps it wasn’t unreasonable for me to have those expectations.

Now of course, this was not an apples-to-apples comparison, far from it. In fact, there are too many uncontrolled variables to list. My reaction might have also been different if the Rudy tape was played first. The Rudy tape was of a classic, breathtaking recording of his that I have long admired. It’s just that hearing that tape didn’t necessarily feel a whole lot different than my experiences listening to the same album at home (Kevin’s amazing playback system aside). I should also mention that I had never heard the first recording by “Engineer X”, so it’s possible that this element of surprise also played a part in that recording’s “wow” factor.

While the Rudy recording was playing, Joe came busting through the door, reference vinyl LPs in hand. He gave me a COVID era-appropriate fist bump. Kevin then pulled a large blue plastic bin from a closet and shoved it across the floor in Joe’s direction. Joe then opened it up to reveal some of the most precious treasures in all the world of music: about a dozen original master tapes dating back to the 1950s and 1960s, all jazz recordings and almost all made with loving care by Rudy Van Gelder.

|

| Joe Harley reaching into the magic blue bin for the day’s tapes |

The Morning Session

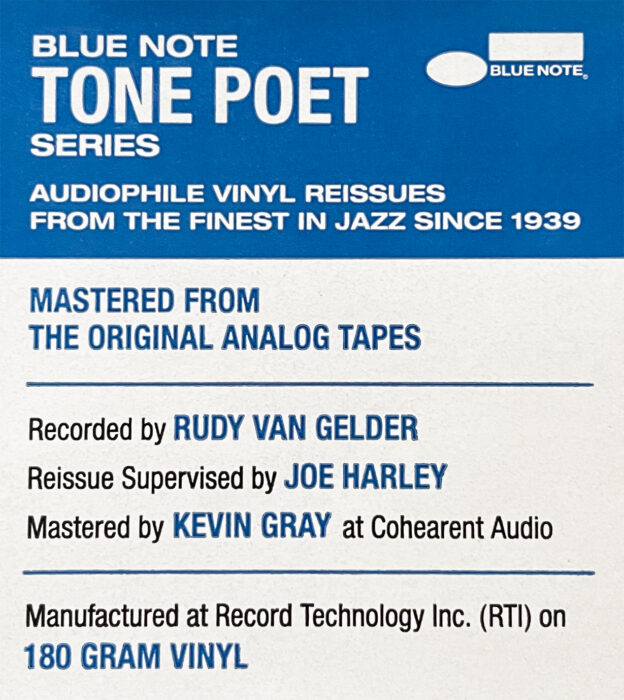

Joe then handed a tape box to Kevin and Kevin started loading it on to a different Studer deck that he uses for most of his mastering work. The tape was of a Blue Note album originally recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack home studio in 1957 (I was asked to not name specific recordings). Before I went to L.A., Joe told me were going to work on this album in the morning and another in the afternoon. Knowing the morning album’s history, I was privately hoping I would get to hear both the original mono and stereo tapes in person, and was pleased that both tapes were in the blue bin.

Joe gave Kevin the mono tape first, and before I knew it we had launched into a comparison of the mono and stereo tapes to decide which would be used for the Tone Poet reissue (slated for next year). Tarik and I sat in the back of the room and quietly watched Joe and Kevin work their magic. The tape was wound “tails out”, a common reel-to-reel tape storage practice intended to avoid audible “print-through”. As such, Kevin rewound past the album’s ending solo piano ballad to a piece featuring the entire band. (Interestingly, the mono master was on a single reel but the stereo was on two reels.)

Joe shifted his chair center to better judge what he was hearing. He and Kevin partook in some inaudible chatter, then Joe got up to put the Japanese stereo reissue he had brought with him on Kevin’s lathe, which doubles as a turntable complete with V-15 playback cartridge and tonearm to the side. The intention was to quickly switch between the mono and stereo presentation, something that couldn’t be done with just one tape machine. Once the record was spinning, there was more inaudible chatter between them, but I did manage to make out that Joe seemed to be favoring the stereo presentation.

|

| Critical listening time with Kevin Gray (left), Joe Harley (center), and my copilot, Tarik Townsend (right) |

Kevin began quickly switching reels from mono to stereo when the song was over. Once he had the stereo reel cued up to the beginning of the first side and playing, it wasn’t long before Joe began singing its praises. He was clearly moving toward using the stereo tape for the reissue, and seemed to have been from the very start.

From where I was sitting, the mono tape sounded pretty darn good. A little bright, but the balance between the musicians was solid. I didn’t know what to make of the comparison between the mono tape and the stereo LP, but once they put the stereo tape on, my first thoughts were, ‘That’s pretty bright,’ and, ‘It sounds like nothing is on the right.’ In all fairness, I was sitting back further than them and I wasn’t close to the sweet spot. Still, the stereo presentation clearly offered a greater sense of width in space.

Prior to this, I noticed that Joe had been reading a 6-by-6 cardboard card that was inside the mono tape box, and a few minutes after the stereo tape had begun playing, Joe explained that someone had left a note about tape damage on the mono tape in a spot we hadn’t heard. That was all it took for him to confirm with Kevin that they were going to use the stereo tape for the Tone Poet reissue. Several minutes later, by the end of the first side, EQ moves and other adjustments contributed to what I felt was a smoother top end and a more even stereo spread (at one point Joe explained that the vinyl manufacturing process would naturally relax the top end a little more as well).

|

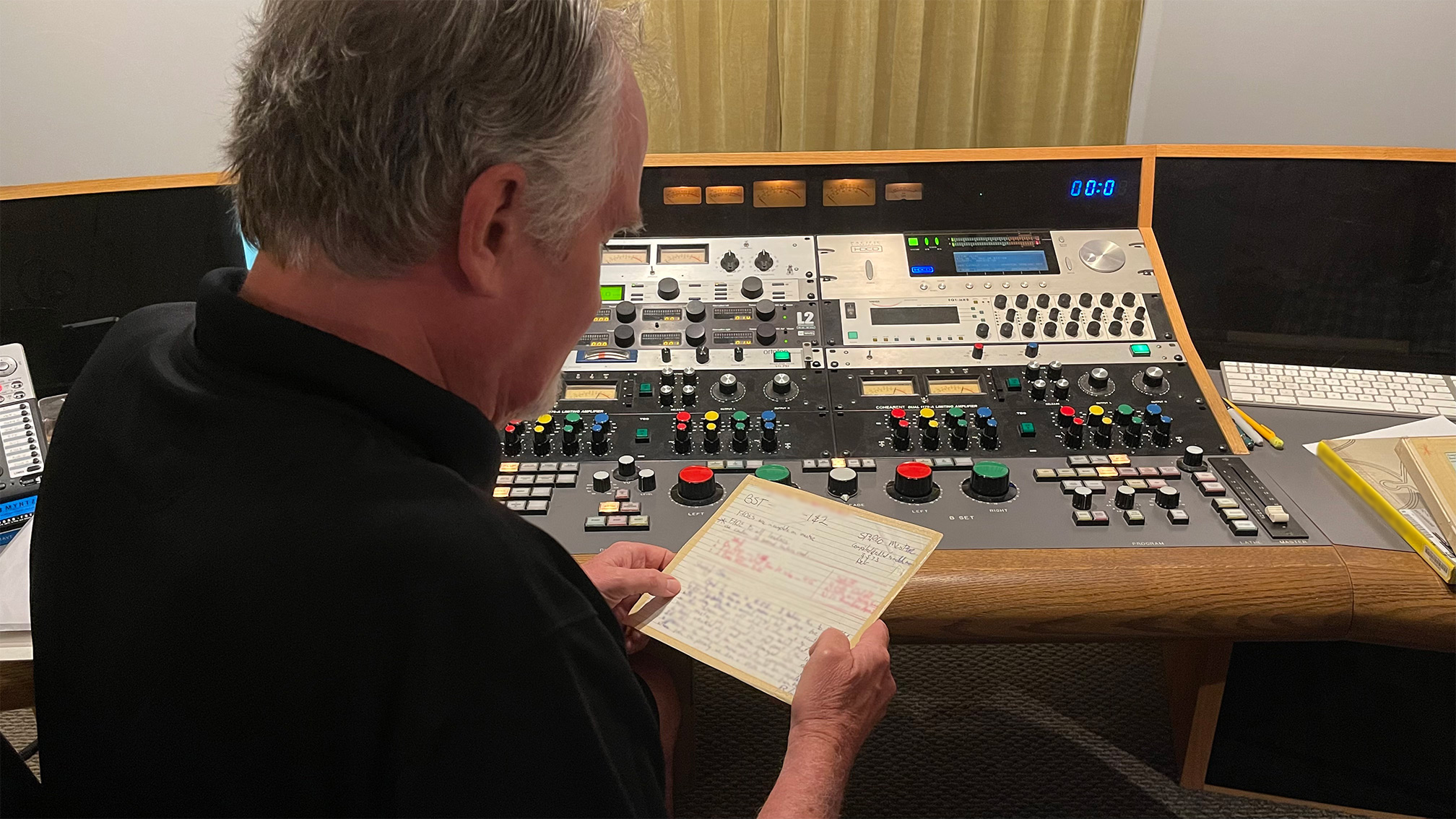

| Joe peering at notes left by a previous mastering engineer |

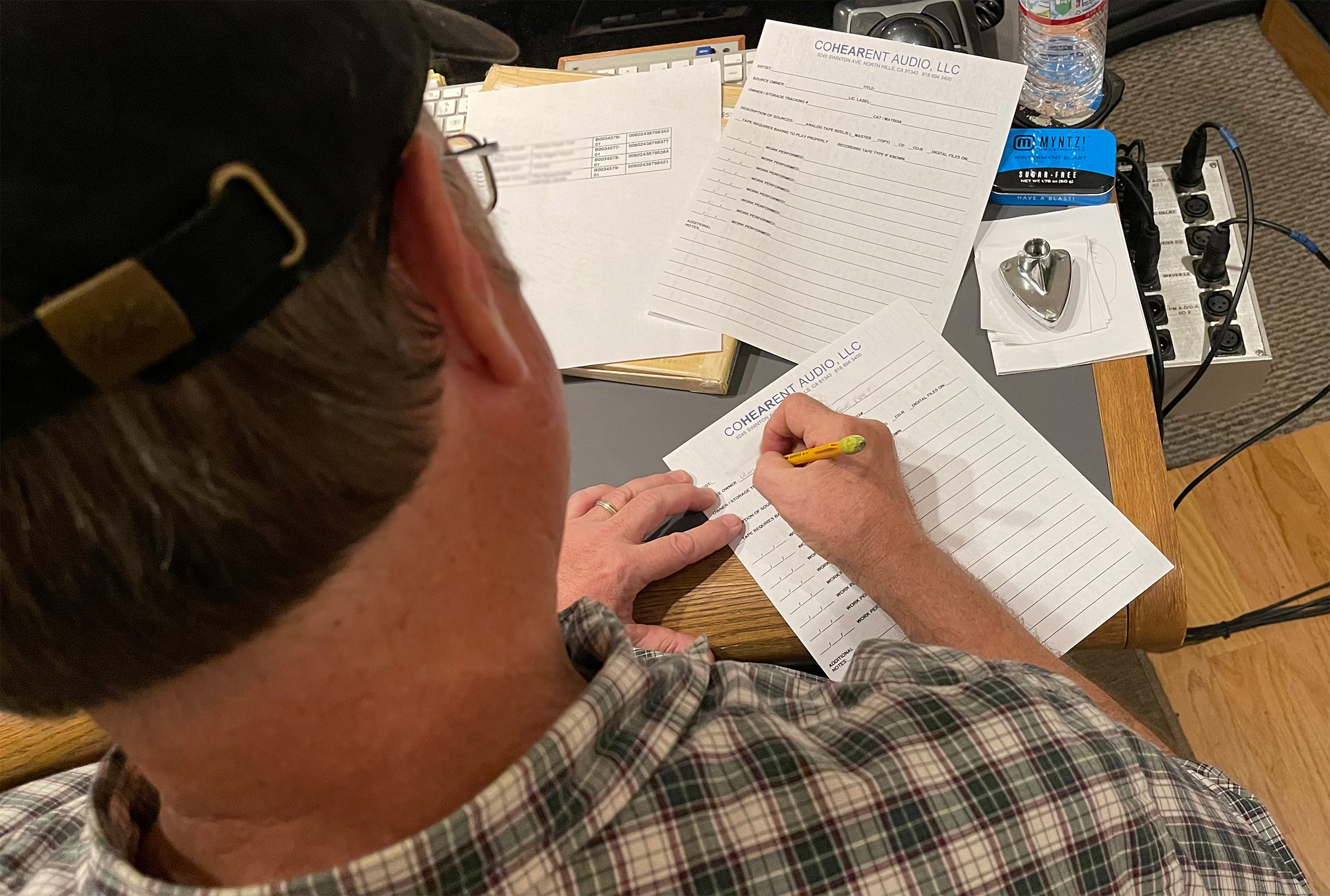

As we listened through the entire album on the stereo reels, we all chatted while Joe and Kevin multitasked. Joe would occasionally make a quick comment to Kevin about the volume levels between tracks, and Kevin kept busy taking his official session notes, which he explained serve the primary purpose of making it easier to go back and redo the mastering should any problems pop up between the lathe and the presses.

|

| Kevin taking session notes |

It was also at this time that I boldly asked Joe and Kevin if I might be able to move my chair up to the center of the console so I could sit at the sweet spot. They happily obliged, and when I did — again, I don’t like to overdramatize these things — it felt like I had stepped in to the Hackensack living room after standing outside the doorway. All the musicians quickly snapped into position, creating a lush stereo image with swirls of airy reverberation bouncing around (sitting between big speakers like Kevin’s, you can’t help but feel wrapped in sound). I had a stronger sense of the soundstage, and the music’s dynamics also became more apparent. Still a little bright to my taste but nonetheless a significant difference compared to when I was sitting further back.

|

| Listening in the sweet spot (Kevin’s monitors are between the curtains, the white strips are the grills) |

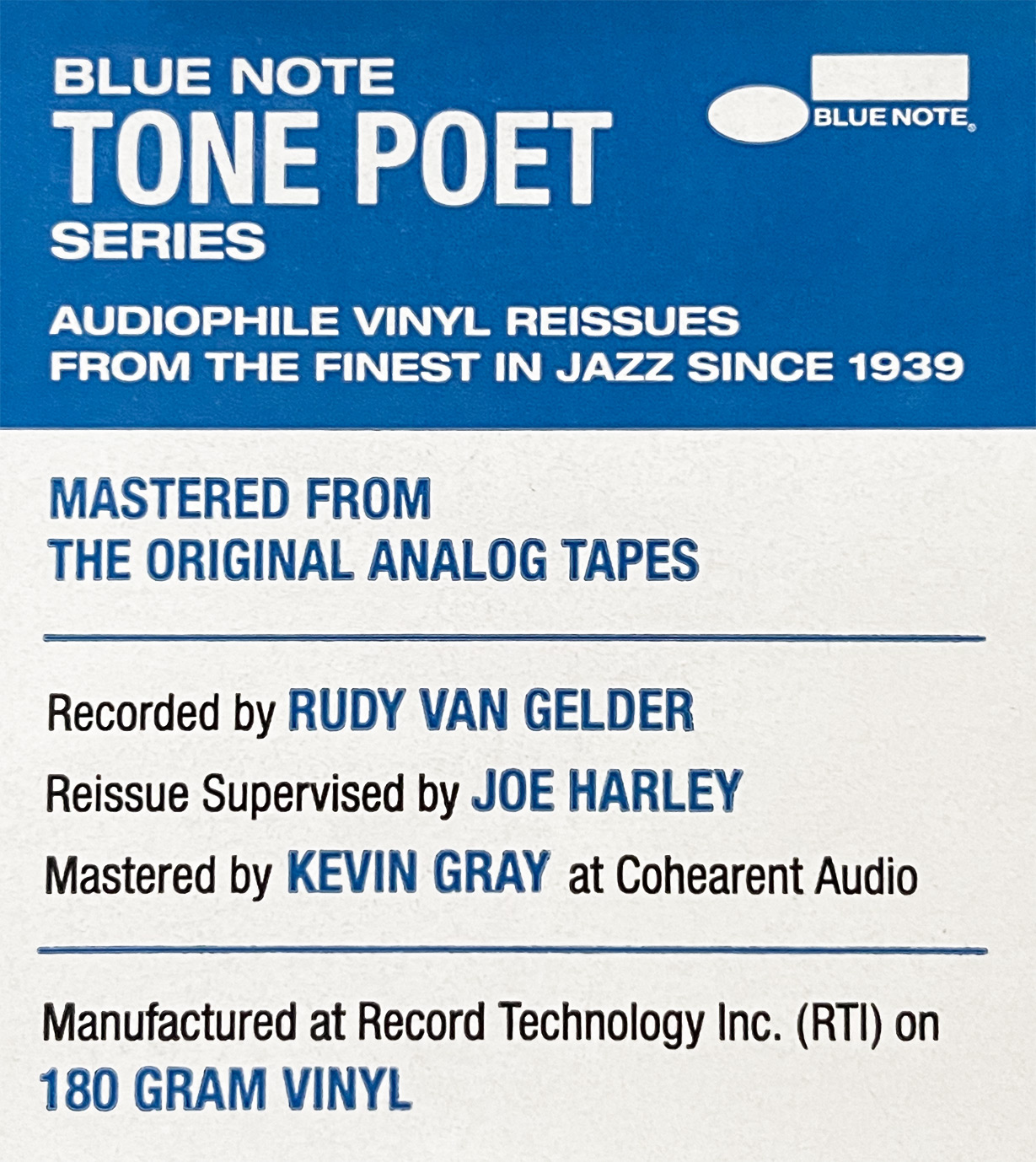

From there, Kevin readied his Neumann lathe to create the lacquer disk masters that would be sent to Record Technology Incorporated, or RTI, for plating and pressing immediately after the session (Kevin hurried off to Fed Ex as soon as we were through with the afternoon session). Joe gave Kevin a gentle reminder: “Did you say you were gonna swap out the cutting stylus?” Before pressing play, Kevin also readied his digital recorder in order to make a high-resolution digital transfer for Blue Note as well. Once the tape was rolling and the lathe was cutting, Kevin was free to talk, but between takes he excused himself so he could implement small fadeouts at the end of each song (there was a note inside the tape box to do so).

|

| Kevin getting ready to do a manual fadeout |

The Afternoon Session

After we went to lunch, we came back for the afternoon session. The album we would be working with was recorded in 1965 at Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. It featured a bigger band and presented a marked difference in sonics. The routine was more or less similar to the morning session, though there was only a stereo tape to be used this time, so no fussing over mono and stereo. After Gray and Harley got a good sonic balance, I once again asked to pull my chair up. Though I had never heard this album before, I was familiar with other work the trumpeter and drummer did for Blue Note from that time period. Here, I heard a more significant difference compared to what I was used to hearing. The sweet spot revealed a very nice balance between all the instruments, and the drummer sounded especially dynamic and realistic compared to other records I had heard him on.

Kevin’s system also seemed to help make the musicians sound less separate than what I was used to. One of my pet peeves about Rudy Van Gelder’s standard stereo spread in the 1960s is that the left channel often feels empty when the saxophonist is soloing on the right alongside the drummer. On Kevin’s system though, the microphone bleed and overall ambience of Van Gelder Studio was more consistently apparent, even in the trumpeter’s absence, which led to both greater cohesiveness within Rudy Van Gelder’s “primitive” stereo mix as well as a stronger sense of spatial balance throughout the performance.

I often listen to music on headphones (while I’m doing other things), where stereo separation is typically exaggerated. But regardless of whether the master tape, Kevin’s rig, or both played a significant role in creating that beautiful spatial balance I heard, I walked away from Cohearent Audio that day having learned a valuable lesson: I have done very little focused listening on good speakers in the sweet spot over the years, and above all I think my experience served as a welcome reminder of how rewarding that type of listening can be.

Once our work had been done, we all began saying our goodbyes. Moments later, just as Joe was opening the door to leave the studio, he paused as if he had forgotten something. Quickly turning to me, in a quiet voice he asked, “So are you going to change the name of your site to Deep Groove Stereo now?”

|

| (L to R) Joe, me, and Kevin |

RVG Legacy: Preserving the Legacy of Rudy Van Gelder

|

| (Photo credit: Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images LLC) |

It is with great pleasure that I announce the launch of RVG Legacy, a new website dedicated to preserving the legacy of Rudy Van Gelder. Since the pandemic has taken away all opportunities for me to give my presentation on Rudy in person, I decided to build a website that would essentially deliver all the content of my talk virtually. In the spring I wrote the narrative, then over the summer I put everything together and developed the site.

Produced in association with Van Gelder Studio and Estate, RVG Legacy features dozens of never-before-seen photos from Rudy’s personal collection, and it is sure to become the definitive one-stop destination for all things Van Gelder. Check out the promotional video below and have fun exploring the world of Rudy Van Gelder!

Making a Case for Rudy Van Gelder’s Importance to the History of Jazz

For regular readers of this blog, recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder needs no introduction. In fact, aside from the musicians themselves, he is probably more known by jazz record collectors than any other figure in the music’s history. For collectors then, any question of Van Gelder’s importance will surely seem puzzling if not flat-out blasphemous.

But not everyone knows how essential Rudy Van Gelder is to the history of jazz. Not everyone knows he was granted a Grammy Trustees Award, one of the highest honors for a non-performing individual working in the music industry. Not everyone knows that he is also a National Endowment of the Arts Jazz Master, a title he shares with other jazz greats like Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gillespie, Artie Shaw, and Quincy Jones. This article was therefore written to provide evidence of just what a colossal force of nature Rudy Van Gelder was as a jazz recording engineer.

National Landmark Status

Around the time of Rudy Van Gelder’s passing in 2016, a small cast of characters began organizing an effort to obtain National Landmark status for Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. For the past year, through my research for a presentation to the Audio Engineering Society, I have been on the periphery of the Landmark application process and privy to witnessing everything unfold.

After receiving feedback from the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office recently (gatekeepers of the National Register for properties in New Jersey), it became clear to Jennifer Rothschild, member of the Closter Historic Preservation Commission and figurehead of the application process, that the case needed to be made for Rudy’s “historical significance”. If your first response to that as a jazz fan is simply, “A Love Supreme” (as was mine), the committee that will eventually hear the studio’s argument for Landmark status needs more than qualitative claims that ultimately amount to opinion; they need factual evidence.

I started to think of possible ways to make a concrete case for Rudy’s historical significance. Jennifer mentioned the likes of Rolling Stone as a publication with enough clout to say something meaningful about the importance of an album like A Love Supreme. That set off a light bulb. Assuming there wouldn’t be time for an in-depth study of multiple publications, what single publication has widespread authority on the history of recorded jazz and thus could somehow demonstrate just how integral Rudy Van Gelder is to the development of the the art form?

The Penguin Guide

I asked for advice from a couple friends with experience in the jazz industry and settled on The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings. Like many jazz fans, I have owned the Penguin guide since I first became interested in the music, and its list of Core Collection albums has long been a guiding light for me in a continual attempt to locate “essential” albums. From this, the idea then became to conduct an analysis not only of how often Rudy’s recordings show up in the Core Collection but also how he fares in comparison to other jazz recording engineers.

|

| The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings |

In the ninth edition of the guide, the definition of “Core Collection” is laid out by authors Richard Cook and Brian Morton:

While one may technically need to read between the lines to extract a notion of “historical significance” here, I think it’s pretty clear that the first albums any music fan might wish to own in an unfamiliar genre are going to be those that are widely considered the most important i.e. historically significant.

Since there is no place in the guide where the Core Collection albums are presented collectively, the world is lucky that a jazz fan named Tom Hull has assembled a list of those albums on his website, assumedly by scouring the entire 1,646-page guide. Using this list of 199 albums, I then proceeded to create a spreadsheet that included engineering credits. (Click here for more information on how the study was conducted and for the complete viewable database.)

The Results

Of the 199 Core Collection albums, 25 were recorded by Rudy Van Gelder in their entirety, with an additional 2 albums containing a portion of material recorded by him, for a total of 27 albums recorded by Van Gelder either entirely or in part. As you will see in the table below of the top engineers represented by the Core Collection, no other recording engineer even came close to Rudy’s tally:

| ENGINEER | YEARS | CREDITS (FULL) | CREDITS (PART) | CREDITS (TOTAL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rudy Van Gelder Van Gelder Studios (New Jersey, U.S.) Blue Note, Impulse, Prestige, Verve, Limelight | 1954-1968 | 25 | 2 | 27 |

| Tom Dowd Atlantic, Audio-Video, Coastal Studios (New York) Atlantic, Bethlehem | 1954-1959 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Doug Hawkins WOR Studios (New York) Blue Note, Dial | 1947-1953 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Jan Erik Kongshaug Rainbow, Talent Studios (Oslo); CTS Studios (London) ECM | 1976-1996 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Val Valentin Capitol Studios (Los Angeles), RCA Studios (New York) Verve, Pablo | 1956-1977 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Bob Fine Fine Sound (New York) Mercury, Verve | 1954-1960 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Martin Wieland Bauer Studios (Ludwigsburg, Germany) ECM | 1974-1978 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Rune Andreasson Radio Sweden (Stockholm) Blue Note, Dragon | 1965-1999 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| David Baker Avatar Studios (New York) ArtistShare, Blue Note, Tiptoe | 1985-2004 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Studio and label affiliations are for Core Collection albums only. For more information on how to interpret this table, please visit the complete viewable database used in this study.

Conclusion

Rudy Van Gelder is an entirely unique figure in the broader history of audio engineering. Perhaps this study provides some evidence of this more universal claim, but for the moment, the Penguin guide suggests that Van Gelder recorded all or part of 27 historically significant jazz albums, which is close to four times as many as any other engineer represented by the guide’s Core Collection. Despite the fact that Rudy Van Gelder’s superhuman output of classic jazz recordings is common knowledge to most jazz fans and nearly all jazz collectors, my hope is that this study puts forth some tangible evidence of this.

Please enjoy the following list of Rudy’s Core Collection albums as well as a Spotify playlist featuring them!

Ed. Note: Of course, the results of this study are solely based on the opinions of the authors of the Penguin guide, and one could easily imagine a more expansive study being done, either entirely within jazz or for all genres, that takes into account the opinions expressed by multiple experts. It should also be noted that the results here are focused on the contributions of recording engineers to the genre of jazz specifically. Were an alternate study done considering all genres of music, the tallies for several engineers (Tom Dowd, Val Valentin, Bob Fine, etc.) would surely more closely approach Van Gelder’s.

Spotify Playlist: RVG Penguin Core Collection (clicking this link opens Spotify in your web browser)

Note: If you are not logged in to Spotify on your web browser, clicking the “play” icon above will only play 30-second clips of the songs. Click any of the embedded links to sign in, open Spotify in your browser, or launch the app on your computer.

Albums Recorded by Rudy Van Gelder in The Penguin Guide’s Core Collection:

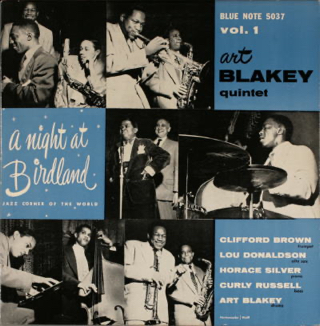

|

Art Blakey A Night at Birdland, Vol. 1 & 2 Blue Note (1954) |

|

J.J. Johnson The Eminent J.J. Johnson, Vol. 1 & 2* Blue Note (1954-55) |

|

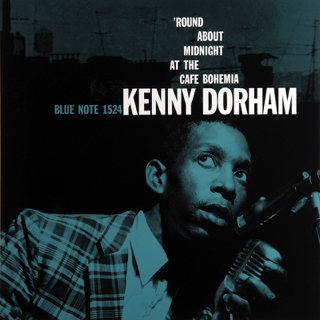

Kenny Dorham ‘Round About Midnight at the Cafe Bohemia Blue Note (1956) |

|

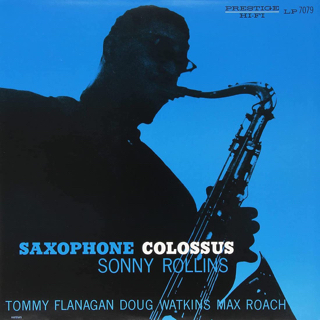

Sonny Rollins Saxophone Colossus Prestige (1956) |

|

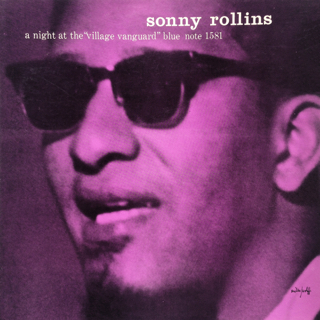

Sonny Rollins A Night at The Village Vanguard Blue Note (1957) |

|

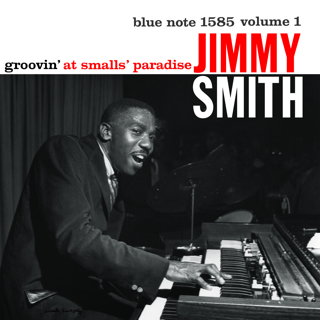

Jimmy Smith Groovin’ at Smalls’ Paradise, Vol. 1 & 2 Blue Note (1957) |

|

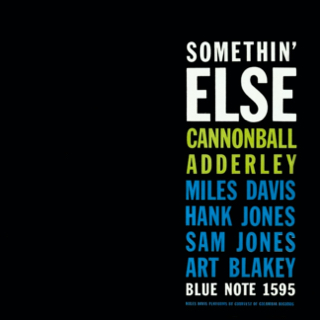

Cannonball Adderley Somethin’ Else Blue Note (1958) |

|

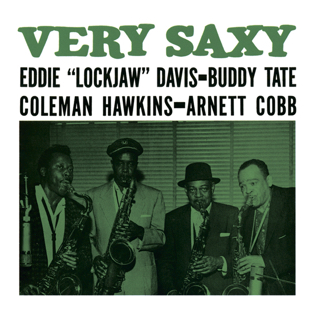

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Very Saxy Prestige (1959) |

|

Horace Silver Blowin’ the Blues Away Blue Note (1959) |

|

Freddie Hubbard Open Sesame Blue Note (1960) |

|

Gil Evans Out of the Cool Impulse (1960) |

|

Grant Green The Complete Quartets with Sonny Clark Blue Note (1961-62) |

|

Jackie McLean Let Freedom Ring Blue Note (1962) |

|

Sheila Jordan Portrait of Sheila Blue Note (1962) |

|

Lee Morgan The Sidewinder Blue Note (1963) |

|

Eric Dolphy Out to Lunch Blue Note (1964) |

|

Andrew Hill Point of Departure Blue Note (1964) |

|

Archie Shepp Four for Trane Impulse (1964) |

|

Anthony Williams Life Time Blue Note (1964) |

|

John Coltrane A Love Supreme Impulse (1964) |

|

Wayne Shorter Speak No Evil Blue Note (1964) |

|

Roland Kirk Rip, Rig and Panic Limelight (1965) |

|

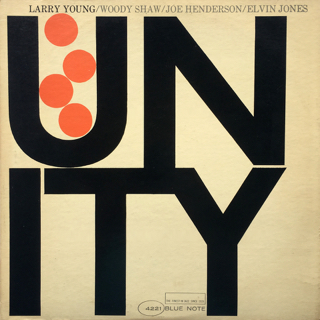

Larry Young Unity Blue Note (1965) |

|

McCoy Tyner The Real McCoy Blue Note (1967) |

|

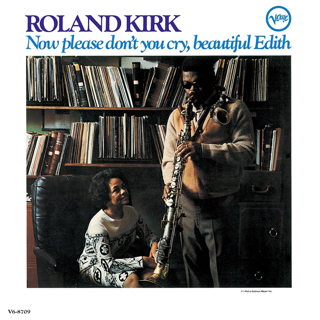

Roland Kirk Now Please Don’t You Cry, Beautiful Edith Verve (1967) |

|

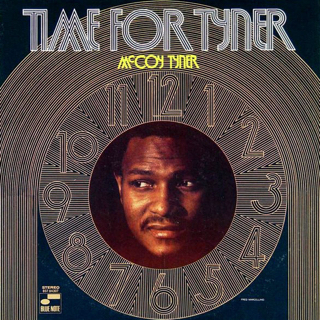

McCoy Tyner Time for Tyner Blue Note (1968) |

* = Albums partially recorded by Rudy Van Gelder

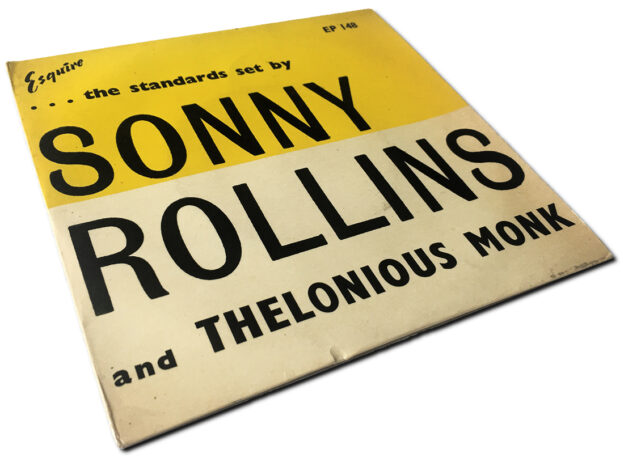

Vinyl Spotlight: Sonny Rollins Quartet (Esquire EP-148) Original 45 RPM 7″ EP

Original 45 RPM 7″ UK pressing circa 1955

Recorded October 25, 1954 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Selection: “I Want to Be Happy” (Caesar-Youmans)

|

| The Columbia GP-3 portable record player |

All the 45s I was buying at that point were doo-wop, rhythm & blues, and rock & roll. Most of the records I proudly consider part of my personal collection, but I was also simultaneously investing in a set of records I could use to get back into DJing. Jazz didn’t necessarily fit into the latter category so I was passing it over when I saw it in the bins. But then I realized how fun it would be to take my GP-3 to the park or bring it along when I travel. To this end, I became more alert to the presence of jazz 45s while shopping both in person and online.

Remember that Esquire Monk ten-inch I posted about a few months ago? While conducting general research on Esquire titles around the time I acquired that record, I decided it might be fun to have some Monk on 45. Then I stumbled upon this title and its glorious cover.

The two songs on this British extended play or “E.P.” first appeared in the U.S. most likely in late 1954 or early 1955 on Prestige catalog number 190, a ten-inch long-play featuring Sonny Rollins and Thelonious Monk. A couple years later the songs would resurface on Prestige 7075, this time a twelve-inch LP that compiled takes from three sessions Rollins and Monk collaborated on in 1953 and ’54. Unfortunately, Rudy Van Gelder is noticeably absent from the mastering process for this E.P., evidenced by the lower signal-to-noise ratio between the music and surface noise.

|

| Prestige catalog numbers 190 and 7075 (photo of 190 courtesy of @jrock1675) |

While I’m a big fan of the music and performances here, I’m not the biggest fan of the actual recording. Van Gelder did record this session, though it was recorded during a period in which he seems to have been fascinated with a shiny new toy, a spring reverberation unit. The result is a Rollins unfavorably drenched in artificial-sounding reflections. The truth is it takes away from my enjoyment of the recording a little, but the performances surely make up for it. I enjoy Monk’s especially heavy-handed comping on “I Want to Be Happy”, and I’ve always liked the melody of Jerome Kern’s “The Way You Look Tonight”, where we find Monk a bit tamer behind Rollins.

Lastly, if it makes sense to call any album covers “sexy”, surely this is one of them. The eye-popping contrast of bold yellow with cream and the cover’s deep black typography demands your attention. Esquire, you have done it again with absolutely killer cover design…hats off.

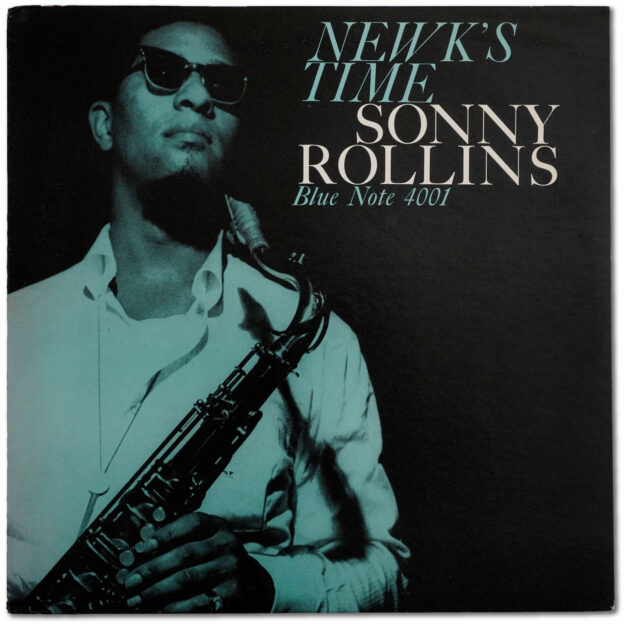

Vinyl Spotlight: Sonny Rollins, Newk’s Time (Blue Note 4001)

- Liberty mono pressing ca. 1966-70

- RVG stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Sonny Rollins, tenor saxophone

- Wynton Kelly, piano

- Doug Watkins, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

Recorded September 22, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released January 1959

| 1 | Tune Up | |

| 2 | Asiatic Raes | |

| 3 | Wonderful! Wonderful! | |

| 4 | Surrey with the Fringe on Top | |

| 5 | Blues for Philly Joe | |

| 6 | Namely You |

Selection:

“Blues for Philly Joe” (Rollins)

This is not the first time that seeing a good deal on a clean original pressing of an album encouraged me to listen to the music more carefully. On this occasion, I was surprised to unearth an album I really enjoy. First and foremost, “Tune Up” and “Asiatic Raes” are two of my favorite modern jazz standards, and this quartet knocks them out of the park. Prematurely, I never thought anyone could best Kenny Dorham’s version of “Asiatic Raes” on Quiet Kenny (titled “Lotus Blossom” there), but Rollins gives him a run for the money.

There are several comical moments from the leader here, and on “Tune Up” we find Rollins at his funniest. His descending staccato riff beginning on the seventh chorus of his solo literally sounds like laughing, and its refrain is a welcome break from the saxophonist’s inventive genius. For someone who is among the most imaginative soloists ever, this less-than-cerebral moment demonstrates Rollins’ sharp wit and special talent for expressing his sense of humor through his music. The lighthearted theme persists throughout the album, but what makes Newk’s Time special is how laid back it feels all while the musicians execute with consistent precision.

Philly Joe Jones shows up for this date and crushes it. His duet with Rollins on “Surrey with the Fringe on Top” is a must-listen. As if the album’s quartet arrangement wasn’t good enough for a minimalist like myself, this pairing of drummer and saxophonist takes it a step further. Although “Surrey” makes it most obvious that engineer Rudy Van Gelder was perhaps a little too heavy-handed with the reverb on Rollins that day, Philly still sounds dry and snappy.

“Blues for Philly” is probably my favorite cut on the album (and for all we know invented on the spot at the session). When the entire band comes back in after “Surrey”, it sounds like an explosion. The low end of Doug Watkins’ bass drops and Wyton Kelly fills the rest of the space with chords. Kelly is especially aggressive and percussive on this album, perhaps rising to match Rollins’ intensity. Everyone is in a good mood and you can hear it.

This sure is one in-your-face album. The entire band is in full attack mode and it makes for an exciting listen.

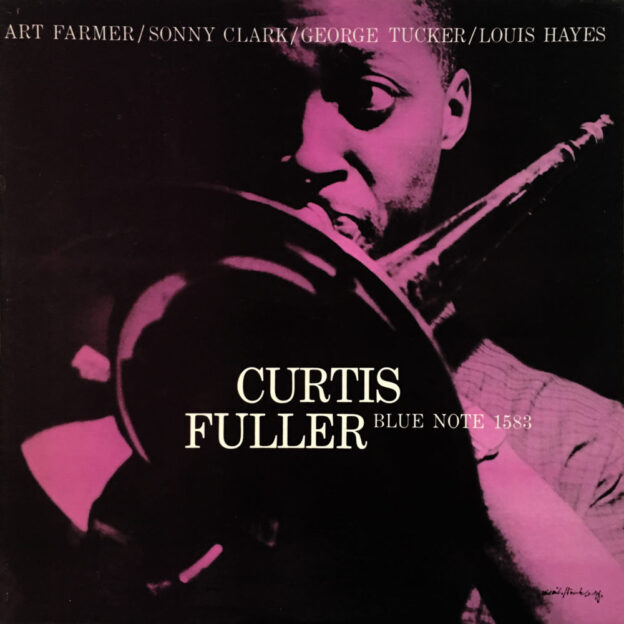

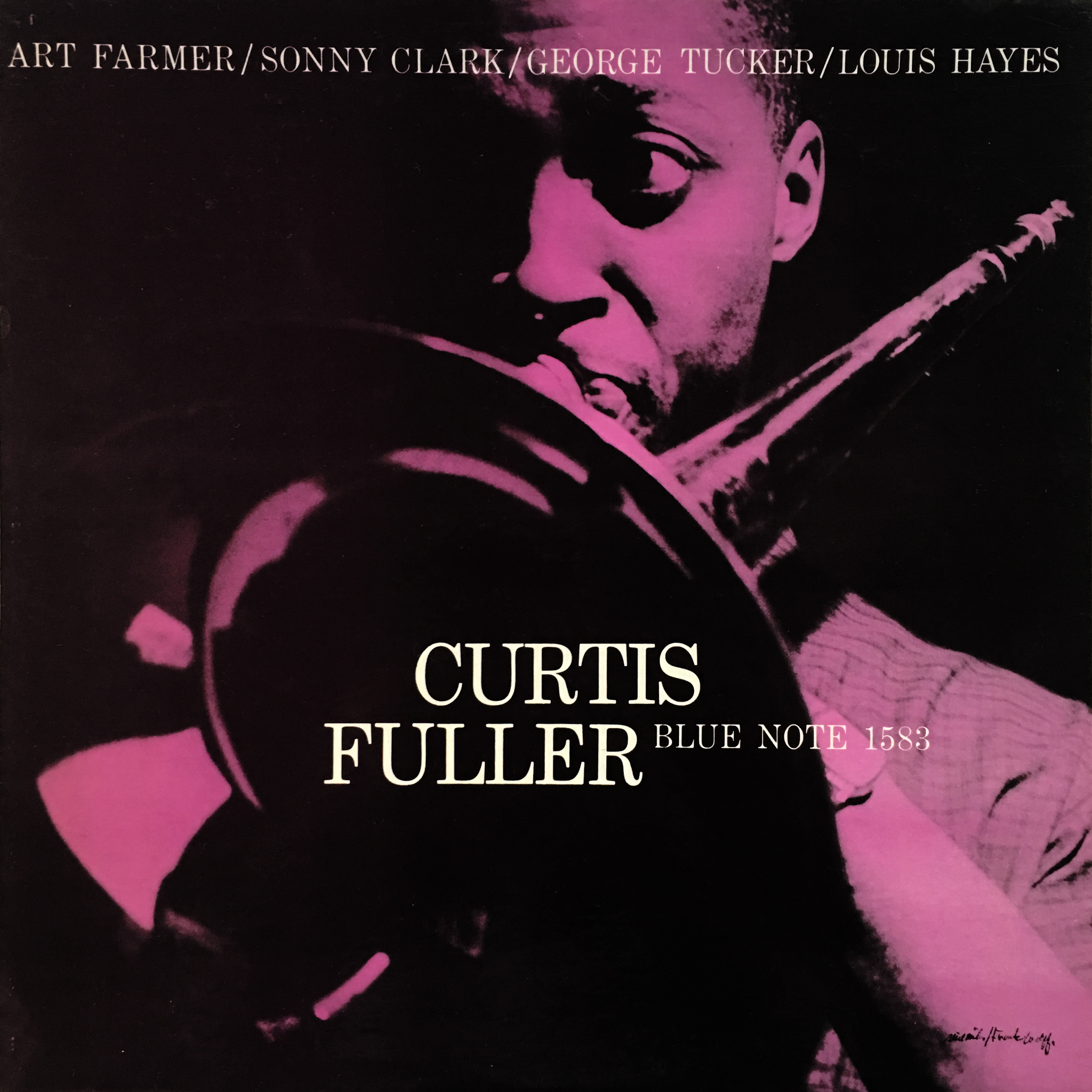

Vinyl Spotlight: Curtis Fuller Volume 3 (Blue Note 1583)

- Earless mono pressing circa 1966

- West 63rd INC/R labels on both sides; no deep groove

- RVG stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Art Farmer, trumpet

- Curtis Fuller, trombone

- Sonny Clark, piano

- George Tucker, bass

- Louis Hayes, drums

Recorded December 1, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released December 1960

Selection:

“Two Quarters of a Mile” (Fuller)

At the time of its recording, Fuller had just hit the New York scene, and his talents as a writer were apparent immediately. Not only did he demonstrate that by contributing four of this album’s six compositions, the dark, brassy harmonies created by Fuller’s trombone and Art Farmer’s trumpet are a testament to his imagination and pursuit of fresh tonalities as an arranger.

Album titles had a tendency to be a little ambiguous in the dawn of the long-play. While the front and back of this jacket simply read, “Curtis Fuller”, the record’s labels suggest Volume 3 as a title (Fuller had led two Blue Note sessions prior to this: The Opener and Bone & Bari). The responsibility of naming an album probably fell squarely in the label’s lap back then, but in all fairness this was par for the course, as many jazz albums of the day had names that either simply echoed a song title or spelled out some cliché play-on-words involving the artist’s name.

Semantics aside, this album is a diamond in the rough. Perhaps because it was released three years after it was recorded, perhaps because it has not been reissued all that much, but also maybe because it does not come across as one of Blue Note’s more sincere branding moments. The cover’s rather basic presentation has a bit of a manufactured feel, and the aforementioned lack of a catchy title may also contribute something to the album’s deceptive front.

Volume 3 begins with a bang. The band explodes out of the gate with a rush of cymbals and a powerful blast from the frontline’s horns on “Little Messenger”. Fuller then proves he can write with latin flavor on “Quantrale”, and drummer Louis Hayes knows how to pepper the rhythm accordingly. Rounding out side one is “Jeanie”, one of several uplifting moments in this moody set. (I’ll always have a soft spot in my heart for songs named after women.)

Side two opens with “Carvon”, a somber ballad that eventually gives way to a more optimistic and uptempo mid-section. Bassist George Tucker’s bow work complements the composition’s downtrodden mood quite well and is reminiscent of Paul Chambers’ reading of “Yesterdays”, recorded earlier that year. But my favorite track is the happy-go-lucky “Two Quarters of a Mile”, which showcases yet another one of Fuller’s catchy melodies. Volume 3 closes with “It’s Too Late Now”, a ballad that opens with glorious unison between the leader and Farmer. Fuller then stretches into one of his patented sweet solos, the likes of which can also be heard on other ballads like “A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening” and “Come Rain or Come Shine”.

The main reason I adore this album is because the musicians, led by Fuller and his heartfelt writing, seem to communicate emotions ranging from happy to sad so genuinely at each and every turn here. Indeed, this was a magical day of synergy for this group of talented musicians, and I’m grateful that its beauty has been preserved all these years.

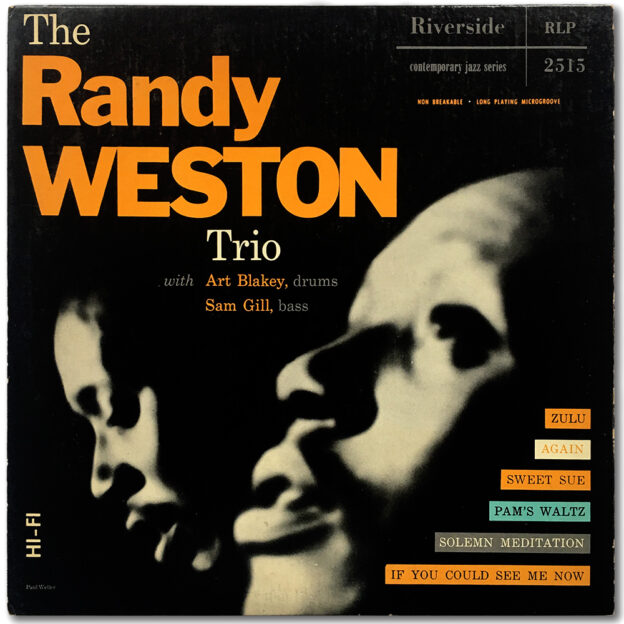

Vinyl Spotlight: The Randy Weston Trio (Riverside 2515) Original 10″ Pressing

Personnel:

- Randy Weston, piano

- Sam Gill, bass

- Art Blakey, drums

Recorded January 25, 1955 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

| 1 | Zulu | |

| 2 | Pam’s Waltz | |

| 3 | Solemn Meditation | |

| 4 | Again | |

| 5 | If You Could See Me Now | |

| 6 | Sweet Sue |

Selection:

“Zulu” (Weston)

Among those albums was this set by Brooklyn pianist Randy Weston, a giant of the keyboard and, standing six-foot-seven, a giant in real life too. In a way, this is “the poor man’s Herbie Nichols”. I don’t mean to discredit Weston in any way when I say that, nor to make any sort of pseudo-scholarly comparison of the two, but while this LP costed a fraction of what an original Nichols ten-inch on Blue Note would (catalog numbers 5068/9), it boasts the same smokey sound, which surely has much to do with the fact that the albums were only recorded four months apart in 1955 and both are Hackensack trio dates featuring Art Blakey on drums.

These early Riverside ten-inches weren’t mastered very hot, so I was lucky to find a clean and quiet copy. And while Van Gelder did not master this album, he manages to make himself heard as the date’s recording engineer nonetheless.

I recently finished Robin Kelley’s Thelonious Monk biography and was delighted to learn of Monk’s close relationship with Weston. I don’t necessarily hear an influence of one on the other, but I’m not a jazz scholar either. My favorite tracks here are the more upbeat ones where Blakey favors sticks over brushes (“Zulu”, “Sweet Sue”, “Solemn Meditation”). Hopefully as I continue to expand my modern jazz palette I will find more gems like this from the early to mid ’50s, an era in the music’s recorded history that has perhaps been somewhat overlooked due to the fact that the classic twelve-inch LP format hadn’t yet arrived as the industry standard.

DGM’s Richard Capeless to Give Talk on Rudy Van Gelder in October

As many of you may know by now, I have long been a big admirer of Van Gelder, which naturally led me to carefully study his life and his work over the past seven years. In 2016 I met Dan Mortensen, then the AES historical track chair, and last year while assisting Dan it was decided that I would give a talk on Van Gelder this year.

I am honored to be presenting Rudy Van Gelder’s story from my perspective, and I have taken steps to make sure my point of view is as comprehensive and unbiased as possible. If you are interested in attending the talk, please click here to visit the AES website and learn more about their All Access passes. If you cannot attend the talk in October, my hope is to give the talk again at a suitable public location for little to no cost at the end of the year.

Here is a summary of the talk as taken from the AES website (click here if you’re interested in seeing my bio over there):

Rudy Van Gelder, or “RVG” as most jazz fans know him, was responsible for laying to tape hundreds of classic jazz recordings spanning a period of over five decades, which were released on a variety of labels including Blue Note, Prestige, Savoy, Impulse, Verve, and CTI.

His rise from obscurity to engineering fame centered on a unique approach to his work, about which he was famously secretive. Beginning in a makeshift living room recording studio in his parents’ Hackensack, New Jersey home, Van Gelder would eventually build a one-of-a-kind cathedral-like studio in nearby Englewood Cliffs that is still in use today.

Always on the cutting edge of technology, Van Gelder used a plethora of state-of-the-art tools to create “the Van Gelder Sound”, a distinct and easily recognizable sonic fingerprint that helped define the sound of jazz on record during the classic analog era of the 1950s and 1960s.

Van Gelder’s legacy is that of an individual who realized his dream to work in a creative capacity, and his story stands to inspire people from all walks of life.

Vinyl Spotlight: Tal Farlow Quartet (Blue Note 5042) Original 10″ Pressing

Personnel:

- Tal Farlow, guitar

- Don Amone, guitar

- Clyde Lombardi, bass

- Joe Morello, drums

Recorded May 11, 1954 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released August 1954

| 1 | Lover | |

| 2 | Flamingo | |

| 3 | Splash | |

| 4 | Rock ‘n’ Rye | |

| 5 | All Through the Night | |

| 6 | Tina |

Selection:

“Rock ‘N’ Rye” (Farlow)

For Collectors

I don’t exactly remember what piqued my interest in this LP. I think it started when I came across a copy of Gil Melle Quintet, Volume 2. Tal Farlow is on that LP. I also think I was just getting into ten-inch LPs and Rudy Van Gelder’s earliest Hackensack recordings. This album is rare in any format. On Spotify there’s only one track buried in an obscure Farlow compilation, and only two tracks are readily available on YouTube. But the tracks I was able to preview sounded good so I sought the album out. White guys playing jazz guitar may have originally steered me clear of a record like this back when I was an ignorant novice collector, but I’m glad I got over my preconceptions and gave this album a chance.

I originally bid on a vinyl-only (no jacket) copy of this last summer on eBay. Though it was described EX, once I got it I only graded it strong VG. But I got such a good deal it didn’t matter (I did, however, politely share my opinion of the seller’s grading with them). Then last month, I caught the collecting bug (yet again), and in the midst of doing some virtual shopping I searched Discogs for a copy that might have a nice jacket. It turned out that the only copy for sale on there had VG vinyl and a VG+ jacket, and not only that, the seller’s store was a 20-minute bus ride away from me in Queens. So I headed out to Ridgewood that weekend and got the record at a discount. A couple weeks later I sold the vinyl from that copy to break even on what I originally paid for the first record, and universal balance had once again been restored.

I’d only grade this vinyl, the original vinyl, strong VG visually, and it has a few pops here and there but nothing repetitive so it is indeed a very strong VG; playback is VG+ for the most part — groove wear is rarer on records like these with quieter arrangements — and I’m very happy to have this record for the price I paid.

For Music Lovers

This is a gorgeous early Hackensack living room recording from April 1954, and additionally a unique quartet combo of two guitars, bass, and drums. It is also one of those rare records that I genuinely enjoy listening to from start to finish. The Farlow compositions (“Splash”, “Rock ‘N’ Rye”, “Tina”) are buoyant bits of songwriting. “Rock ‘N’ Rye” listens like a jazz song with a hook, and employs fun use of artificial reverb at the end to make it sound like Farlow and co-guitarist Don Amone are retreating to a cave to jam the night away whilst never abandoning their instruments. “Flamingo”, the record’s ballad, is a sweet tune where Farlow puts his virtuous playing down for a take, opting for some pretty, minimalist plucking. The album is cool and quiet but manages to remain generally upbeat and thus makes for good listening in a multitude of settings.

If you’re interested in owning a copy, a relatively rare United Artists ten-inch pressing from the ‘70s exists. Perhaps it will be a bit easier to acquire one of the Japanese Toshiba reissues from the ‘90s, either the twelve-inch or ten-inch version. Japan also reissued the album on CD. Unfortunately, my understanding is that all of these reissues embody some measure of master tape issues, but options are obviously limited to listen to this great music.

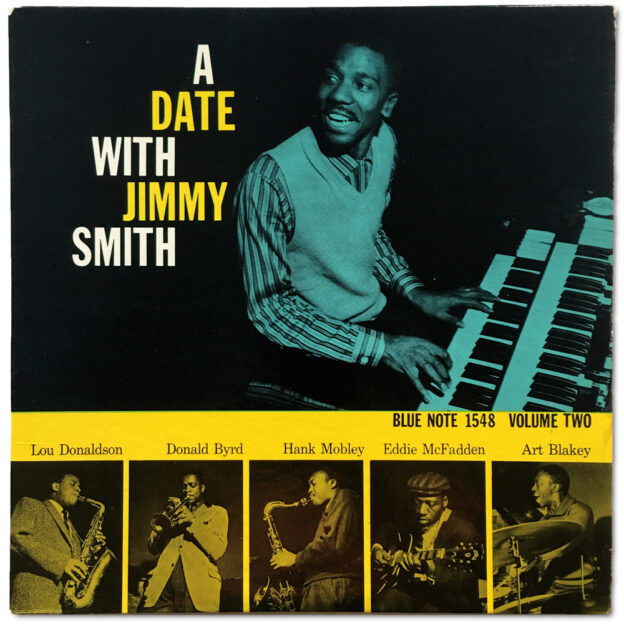

Vinyl Spotlight: A Date with Jimmy Smith, Vol. 2 (Blue Note 1548) “W63/NY” Mixed Labels Pressing

- Vintage pressing circa 1962-1966

- “West 63rd (no R) / New York USA” mixed labels

- “RVG” and Plastylite “P” (ear) etched in dead wax

Personnel:

- Donald Byrd, trumpet

- Lou Donaldson, alto saxophone

- Hank Mobley, tenor saxophone

- Jimmy Smith, organ

- Eddie McFadden, guitar

- Art Blakey, drums

Recorded February 11 & 12, 1957 at Manhattan Towers, New York City

Originally released September 1957

Selection:

“Groovy Date” (Mobley)

When I started collecting, I bought into the popular opinion that Jimmy Smith isn’t “collectible” and didn’t pay him any attention. But then I found a great 1965 German documentary on him serving as evidence of how “incredible” he really was. From the live performances where he plays with so much heart and frankly, tears it up, to the interview moments where he communicates his philosophy of jazz and music in general so well, I decided to start listening. So I made a Spotify playlist of all his Blue Note albums, put it on shuffle while I worked, and a couple weeks later I had a condensed playlist of favorites (you can hear that playlist on Spotify now). One of those songs, “Groovy Date”, is from this LP. The sheer power with which the song opens and closes was enough to make me hit the “heart” button, and the solos from all the members do not disappoint.

Despite this album being available only in mono regardless of format, many Smith Blue Notes are only available in stereo as reissues. So I decided it would be both worthwhile and cost-effective to pursue these albums in their original mono LP incarnations. Since Smith originals are so readily available, I quickly acquired six of them. This one was a little harder to get online, but then one day I was in a local shop and they had this copy for cheap. The cover looked great but the vinyl was pretty marked up. It doesn’t play with any skips, and aside from “Groovy Date”, it can be a little noisy. That’s fine with me because my favorite track sounds bold and clear, and I basically chalk this up as paying a fair price for a single song and a great cover (I love the photos of the musicians, the layout, and the color scheme).

As for one of my favorite topics, sonics, this is one of a handful of Blue Note albums recorded by Rudy Van Gelder that wasn’t recorded at one of his studios or a live venue. For years I noticed the recording location “Manhattan Towers” for various Blue Note recordings on jazzdisco.org but never knew what it meant. But then, one day I was lucky enough to speak with Blue Note producer and archivist Michael Cuscuna about it, and he explained that Blue Note had worked out a deal with Manhattan Towers, a hotel in New York City’s Upper West Side, so bigger bands could assemble in their ballroom (Art Blakey’s percussion ensembles, Sabu Martinez) and important artists like Smith who liked to record at night could jam after the normal Hackensack business hours (Van Gelder’s neighbors were known to complain about the noise late at night and his parents lived there).

In writing this article I did a little research and found this cool New York Times article from 1974 explaining that the hotel, located on Broadway between West 76th and 77th Streets, was crime-ridden! (One has to wonder if it was similar or becoming more that way in 1957!) You can hear the massive size of that ballroom on these cuts. The horns, organ, and guitar still sound quite immediate and up-close, but the reverberation of Art Blakey’s drums is true to the space’s larger size. Stay tuned as I review more of Jimmy Smith’s classic Blue Note recordings in the coming months.