For regular readers of this blog, recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder needs no introduction. In fact, aside from the musicians themselves, he is probably more known by jazz record collectors than any other figure in the music’s history. For collectors then, any question of Van Gelder’s importance will surely seem puzzling if not flat-out blasphemous.

But not everyone knows how essential Rudy Van Gelder is to the history of jazz. Not everyone knows he was granted a Grammy Trustees Award, one of the highest honors for a non-performing individual working in the music industry. Not everyone knows that he is also a National Endowment of the Arts Jazz Master, a title he shares with other jazz greats like Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gillespie, Artie Shaw, and Quincy Jones. This article was therefore written to provide evidence of just what a colossal force of nature Rudy Van Gelder was as a jazz recording engineer.

National Landmark Status

Around the time of Rudy Van Gelder’s passing in 2016, a small cast of characters began organizing an effort to obtain National Landmark status for Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. For the past year, through my research for a presentation to the Audio Engineering Society, I have been on the periphery of the Landmark application process and privy to witnessing everything unfold.

After receiving feedback from the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office recently (gatekeepers of the National Register for properties in New Jersey), it became clear to Jennifer Rothschild, member of the Closter Historic Preservation Commission and figurehead of the application process, that the case needed to be made for Rudy’s “historical significance”. If your first response to that as a jazz fan is simply, “A Love Supreme” (as was mine), the committee that will eventually hear the studio’s argument for Landmark status needs more than qualitative claims that ultimately amount to opinion; they need factual evidence.

I started to think of possible ways to make a concrete case for Rudy’s historical significance. Jennifer mentioned the likes of Rolling Stone as a publication with enough clout to say something meaningful about the importance of an album like A Love Supreme. That set off a light bulb. Assuming there wouldn’t be time for an in-depth study of multiple publications, what single publication has widespread authority on the history of recorded jazz and thus could somehow demonstrate just how integral Rudy Van Gelder is to the development of the the art form?

The Penguin Guide

I asked for advice from a couple friends with experience in the jazz industry and settled on The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings. Like many jazz fans, I have owned the Penguin guide since I first became interested in the music, and its list of Core Collection albums has long been a guiding light for me in a continual attempt to locate “essential” albums. From this, the idea then became to conduct an analysis not only of how often Rudy’s recordings show up in the Core Collection but also how he fares in comparison to other jazz recording engineers.

|

| The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings |

In the ninth edition of the guide, the definition of “Core Collection” is laid out by authors Richard Cook and Brian Morton:

While one may technically need to read between the lines to extract a notion of “historical significance” here, I think it’s pretty clear that the first albums any music fan might wish to own in an unfamiliar genre are going to be those that are widely considered the most important i.e. historically significant.

Since there is no place in the guide where the Core Collection albums are presented collectively, the world is lucky that a jazz fan named Tom Hull has assembled a list of those albums on his website, assumedly by scouring the entire 1,646-page guide. Using this list of 199 albums, I then proceeded to create a spreadsheet that included engineering credits. (Click here for more information on how the study was conducted and for the complete viewable database.)

The Results

Of the 199 Core Collection albums, 25 were recorded by Rudy Van Gelder in their entirety, with an additional 2 albums containing a portion of material recorded by him, for a total of 27 albums recorded by Van Gelder either entirely or in part. As you will see in the table below of the top engineers represented by the Core Collection, no other recording engineer even came close to Rudy’s tally:

| ENGINEER | YEARS | CREDITS (FULL) | CREDITS (PART) | CREDITS (TOTAL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rudy Van Gelder Van Gelder Studios (New Jersey, U.S.) Blue Note, Impulse, Prestige, Verve, Limelight | 1954-1968 | 25 | 2 | 27 |

| Tom Dowd Atlantic, Audio-Video, Coastal Studios (New York) Atlantic, Bethlehem | 1954-1959 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Doug Hawkins WOR Studios (New York) Blue Note, Dial | 1947-1953 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Jan Erik Kongshaug Rainbow, Talent Studios (Oslo); CTS Studios (London) ECM | 1976-1996 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Val Valentin Capitol Studios (Los Angeles), RCA Studios (New York) Verve, Pablo | 1956-1977 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Bob Fine Fine Sound (New York) Mercury, Verve | 1954-1960 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Martin Wieland Bauer Studios (Ludwigsburg, Germany) ECM | 1974-1978 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Rune Andreasson Radio Sweden (Stockholm) Blue Note, Dragon | 1965-1999 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| David Baker Avatar Studios (New York) ArtistShare, Blue Note, Tiptoe | 1985-2004 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Studio and label affiliations are for Core Collection albums only. For more information on how to interpret this table, please visit the complete viewable database used in this study.

Conclusion

Rudy Van Gelder is an entirely unique figure in the broader history of audio engineering. Perhaps this study provides some evidence of this more universal claim, but for the moment, the Penguin guide suggests that Van Gelder recorded all or part of 27 historically significant jazz albums, which is close to four times as many as any other engineer represented by the guide’s Core Collection. Despite the fact that Rudy Van Gelder’s superhuman output of classic jazz recordings is common knowledge to most jazz fans and nearly all jazz collectors, my hope is that this study puts forth some tangible evidence of this.

Please enjoy the following list of Rudy’s Core Collection albums as well as a Spotify playlist featuring them!

Ed. Note: Of course, the results of this study are solely based on the opinions of the authors of the Penguin guide, and one could easily imagine a more expansive study being done, either entirely within jazz or for all genres, that takes into account the opinions expressed by multiple experts. It should also be noted that the results here are focused on the contributions of recording engineers to the genre of jazz specifically. Were an alternate study done considering all genres of music, the tallies for several engineers (Tom Dowd, Val Valentin, Bob Fine, etc.) would surely more closely approach Van Gelder’s.

Spotify Playlist: RVG Penguin Core Collection (clicking this link opens Spotify in your web browser)

Note: If you are not logged in to Spotify on your web browser, clicking the “play” icon above will only play 30-second clips of the songs. Click “Play on Spotify” or the Spotify logo to launch the app on your computer.

Albums Recorded by Rudy Van Gelder in The Penguin Guide’s Core Collection:

|

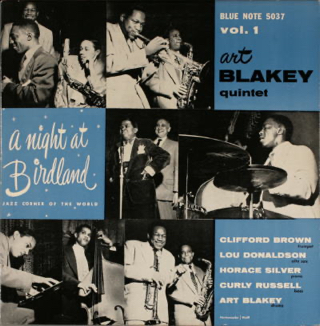

Art Blakey A Night at Birdland, Vol. 1 & 2 Blue Note (1954) |

|

J.J. Johnson The Eminent J.J. Johnson, Vol. 1 & 2* Blue Note (1954-55) |

|

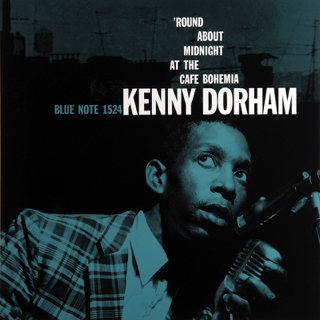

Kenny Dorham ‘Round About Midnight at the Cafe Bohemia Blue Note (1956) |

|

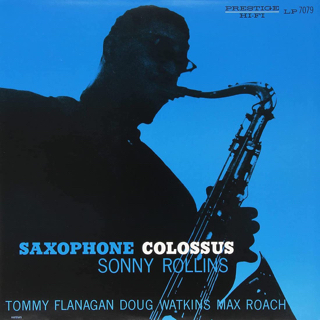

Sonny Rollins Saxophone Colossus Prestige (1956) |

|

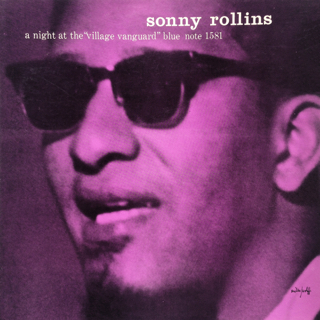

Sonny Rollins A Night at The Village Vanguard Blue Note (1957) |

|

Jimmy Smith Groovin’ at Smalls’ Paradise, Vol. 1 & 2 Blue Note (1957) |

|

Cannonball Adderley Somethin’ Else Blue Note (1958) |

|

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Very Saxy Prestige (1959) |

|

Horace Silver Blowin’ the Blues Away Blue Note (1959) |

|

Freddie Hubbard Open Sesame Blue Note (1960) |

|

Gil Evans Out of the Cool Impulse (1960) |

|

Grant Green The Complete Quartets with Sonny Clark Blue Note (1961-62) |

|

Jackie McLean Let Freedom Ring Blue Note (1962) |

|

Sheila Jordan Portrait of Sheila Blue Note (1962) |

|

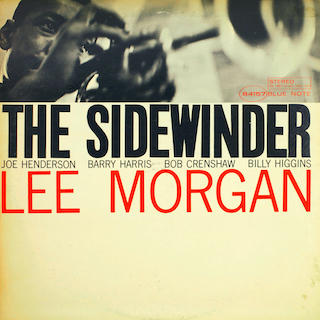

Lee Morgan The Sidewinder Blue Note (1963) |

|

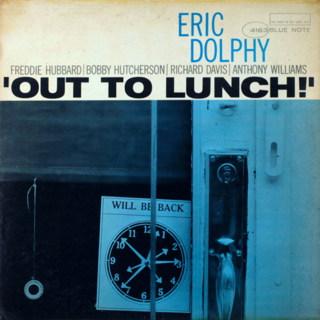

Eric Dolphy Out to Lunch Blue Note (1964) |

|

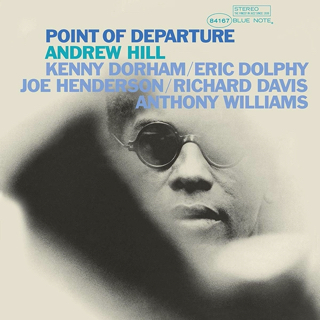

Andrew Hill Point of Departure Blue Note (1964) |

|

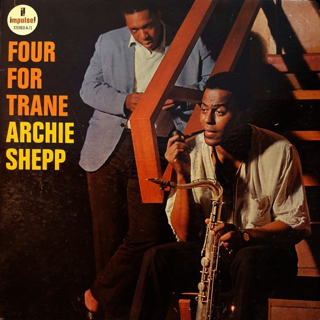

Archie Shepp Four for Trane Impulse (1964) |

|

Anthony Williams Life Time Blue Note (1964) |

|

John Coltrane A Love Supreme Impulse (1964) |

|

Wayne Shorter Speak No Evil Blue Note (1964) |

|

Roland Kirk Rip, Rig and Panic Limelight (1965) |

|

Larry Young Unity Blue Note (1965) |

|

McCoy Tyner The Real McCoy Blue Note (1967) |

|

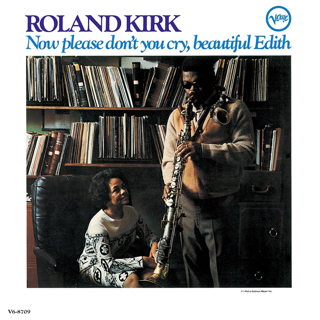

Roland Kirk Now Please Don’t You Cry, Beautiful Edith Verve (1967) |

|

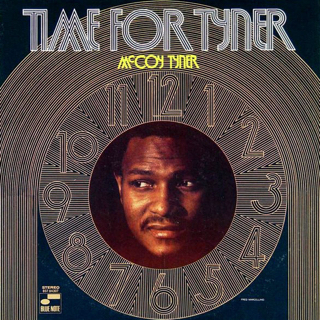

McCoy Tyner Time for Tyner Blue Note (1968) |

* = Albums partially recorded by Rudy Van Gelder