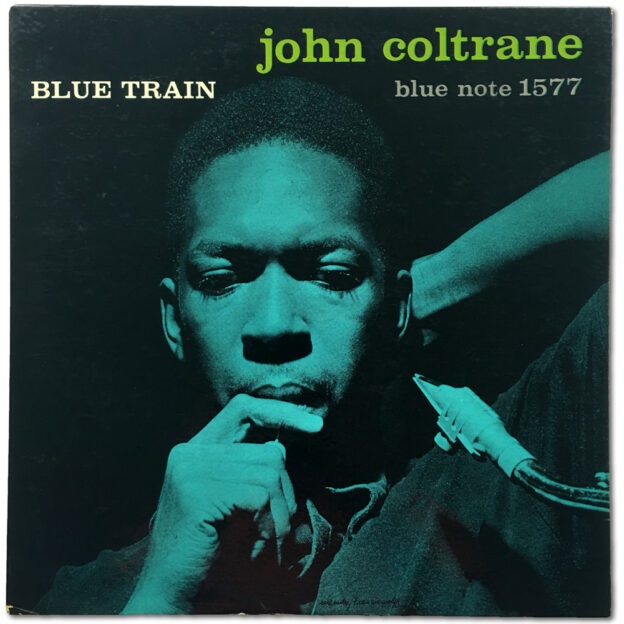

- “Second” mono pressing circa 1959

- “BLUE NOTE RECORDS INC / 47 WEST 63RD / NYC” on both labels with registered trademark “R”

- Deep groove both sides

- Plastylite “P” etched and “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel

- Lee Morgan, trumpet

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Curtis Fuller, trombone

- Kenny Drew, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

Recorded September 15, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released November 1957

Selections:

“Blue Train”

“Moment’s Notice”

For Music Lovers

I’m surprised by how many people recommend this album to jazz novices because I don’t necessarily find it to be an “accessible” listen. Slowly it has become one of my favorite jazz albums but I didn’t like it initially and ignored it for quite some time. I find Coltrane’s solos here challenging, and this next comment may not be something most people can identify with, but I initially found many of the melodies to sound “major” in terms of scale and thus maybe a little old-fashioned (no pun intended) at a time when I was looking for something more edgy and “minor”.

Growing out of my fashionable pessimism phase, I’ve come to appreciate older-sounding jazz numbers. But there’s a sort of hidden darkness looming in between the heads of the songs here. “Moment’s Notice”, an album favorite of mine, is the prime example of this: its happy, soulful theme seems to deceitfully change from major to minor key at the renewal of each chorus.

One by one, I grew to adore each and every song on this album. “I’m Old Fashioned”, a standard written by songwriting juggernauts Jerome Kern and Johnny Mercer, initially sounded like a cookie-cutter ballad but ultimately won me over. On “Lazy Bird”, trumpeter Lee Morgan’s quiet introductory proclamation of the theme is a welcome break from the sheer power of this all-star sextet. But what hasn’t already been said about the album’s mega-classic title track? The simple 24-bar theme is one of the most famous intros in all of jazz, and Coltrane’s solo has been exhaustively picked apart by scholars. No more than forty seconds after the album’s first notes sound, the leader launches this mazeltov cocktail at the listener. It was too intense for me as a jazz newcomer, but over the years I feel I have grown to better understand Coltrane’s music, and today I marvel at the flurry of notes played here. In my view of jazz history this marks the beginning of Coltrane’s revolution: uninspired by what he was hearing at the time, it is the moment when the saxophonist took his instrument and proclaimed to the jazz world, “Enough is enough, it’s time to push this music forward.”

|

| John Coltrane approaching Rudy Van Gelder’s Telefunken U47 microphone |

On a side note, two weeks prior to the recording of this album in mid-September 1957, Coltrane was in the studio as a sideman for the recording of Sonny’s Crib (Blue Note 1576). That album’s title track bears a striking resemblance to the minimal, bluesy progression in “Blue Train”. Was Coltrane inspired by Sonny Clark? Had he taken Clark’s idea and ran with it? We may never know if there was a conscious connection between the two songs in Coltrane’s mind (“Sonny’s Crib” was not necessarily written first just because it was recorded first) but I found it worth mentioning.

|

| BLP 1576, Sonny’s Crib |

The choice of lineup on Blue Train is interesting. Coltrane was not known to have a regular working relationship with either Kenny Drew or Lee Morgan (he had recorded with each of them once on separate occasions prior to this date), which leaves open the possibility that Drew and Morgan were suggested by Blue Note producer Alfred Lion. This seems more plausible in the case of Morgan, a regular leader with the label. Though the album proved a grand slam for Blue Note in terms of sales, it was ultimately a one-off recording Trane did for them.

|

| Coltrane, Morgan, and Curtis Fuller (off camera) rehearsing before a take |

Critics seem split as to the brilliance of Blue Train. Beyond the title track, I have read reviews suggesting that the album amounts to little more than a run-of-the-mill bop date. The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, while awarding it four stars, also manages to call it “an overvalued record”. I personally find the music jubilant and adventurous. The pairing of Trane with Morgan doesn’t create a seamless fusion to me, but it’s interesting to hear how Morgan responds to being thrown into such a foreign situation.

For Collectors

My experiences with vinyl versions of this album began many years ago with the 2005 Classic Records mono reissue. Though visually near mint, that copy had significant surface noise (a problem I’ve sadly run into again and again with Classic reissues — not all, but most). After ditching that copy, I spent several years getting more familiar with the material by listening to the 2003 stereo RVG Edition CD before I acquired the 2014 Music Matters mono reissue. I’m not nearly as fanatical about Music Matters as most jazz fans, but the fact that they released this as a single 33 R.P.M. disc in mono got my attention. Mastered by Kevin Gray, it is sonically astonishing. Through all this, I’ve always kept my eye on auctions for the rarer “NEW YORK USA” mono reissues of this with the RVG stamp and ear. These pressings sell for much less than copies brandishing some form of the “West 63rd NYC” address on the labels, but I was always outbid.

Fast forward to 2018. About a month ago I was in an esteemed NYC record store and there on the counter sat a stack of clean looking vintage jazz records. “Excuse me, are these for sale?”, I asked. “Those aren’t for sale,” the owner quipped, though he did add that the records would be available in the coming days. As I was leaving, I did see the owner pull this copy of Blue Train out of the stack for inspection, though I didn’t really think much of it at the time. Later that week, that record showed up in the store’s Instagram feed along with a couple other choice jazz albums. This was definitely a case of seeing a collection of clean records that were undoubtedly cared for by a single owner, such a rare occurrence that it makes you feel like you need to go home with at least one of them. So I acted fast. I hopped in the shower, threw some clothes on, and headed for the train hoping to beat the rush.

On the way there I was texting with a friend and we were predicting the price tag on Blue Train, so when I walked in the door and peered at the sticker from the other side of the counter I was amazed to find that the number was close to half of my higher estimate. The labels were gorgeous, the vinyl was incredibly flat and weighty, and the original plain paper sleeve was included — a sign that it was an earlier West 63rd “INC/R” pressing. But most importantly, the vinyl was out-of-sight beautiful, with only two light unfeelable marks. Normally I want to listen to the record before a bigger purchase like this, but this was unquestionably a top copy so there was no hesitation on my behalf to throw my money down. When I got home, the playback did not disappoint in any way, and the LP really looks and plays as if I bought it new…no need to ever “upgrade” to an earlier pressing down the road with this one.

Speaking of pressings, there is a hotly-contested debate over what constitutes a “first pressing” of this album. While fundamentalists will insist that only copies brandishing the “NEW YORK 23” address on one side should be considered first pressings, these copies are so rare that many collectors are left to conclude that “WEST 63RD” copes without the “INC” or registered trademark “R” must have also been part of that initial run. I side with the latter camp, considering all of these copies firsts, which would make this copy a second pressing (notice my quotes around the word “second” in the description above). Some collectors, including the venerable Larry Cohn, even go as far as suspecting that the New York 23 copies are second pressings. Semantics aside, this is an absolutely stunning copy of this classic and one of the cleanest vintage jazz records in my collection.

|

| The elusive “NEW YORK 23” label |

I’m not usually one to sweat the details when it comes to various runs of album jackets, but through a bit of recent research I have come to realize that there is a small difference between the first and second pressings of this jacket despite the “West 63rd Street” address appearing on both: while second jackets have black printing artifacts on the photo of Curtis Fuller, first jackets do not.

|

| Original (left) and second edition (right) jackets |

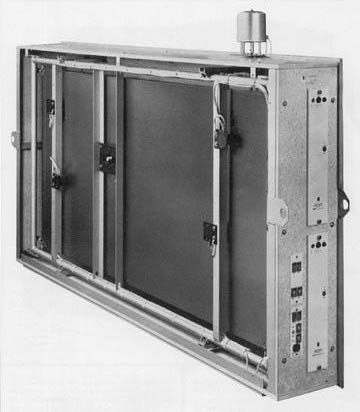

Though engineer Rudy Van Gelder is famous for his high level of sonic consistency, careful inspection will expose a multitude of different approaches both he and producer Alfred Lion took to the recording and mixing processes. Blue Train is an ideal example of this. The dead-black background depicted on the cover compliments the “nighttime” vibe of this recording exceedingly well. This is partly due to the fact that the album was laid to tape not long after Van Gelder acquired his new EMT plate reverb unit. This replaced his old (and frankly, cheap-sounding) “spring” reverb unit, which to the dismay of many jazz fans plagues numerous earlier Hackensack recordings by saturating the soundstage with choppy echoes of horns and drums. And while stereo versions of Blue Train present a rather disjointed soundstage (instruments on the far left and right with the reverb alone in the center), the unified mono presentation of the music here coupled with the roomy decay of the mono EMT plate succeeds at creating a spacious, dark soundstage that’s as far as one might imagine from the natural characteristics of a makeshift living room studio. And while the true-to-life sonic character of that room has appeared on countless jazz recordings and been celebrated for decades, this is a shining example of a time when Van Gelder and Lion decided that the music and temperaments of the artists required a fresh approach.

|

| EMT reverb plate |

It really doesn’t get any better than this when it comes to a vintage jazz listening experience: a clean copy of a classic album with a star-studded, exceptionally recorded cast being presented in monophonic fidelity as originally intended. It’s a time machine back to that cool autumn day in 1957 when jazz giants roamed Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey living room, expressing themselves the best way they knew how. This is an album I will cherish when I’m old and grey, and it is sure to get lots and lots of plays from now until then.