Tag Archives: Jazz

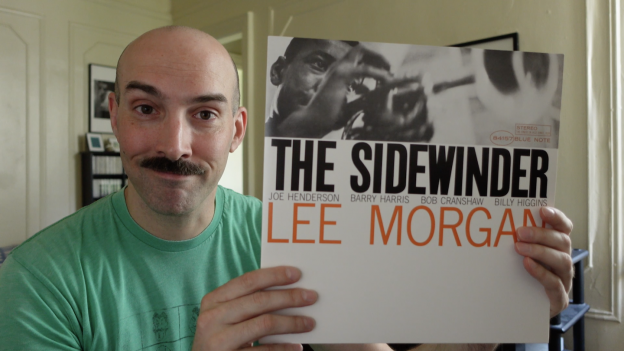

Introducing “Video Vinyl Spotlight”, A New DGM YouTube Series

I’m back, once again. Vinyl Spotlight posts began back in January 2014 and have been a cornerstone of this blog for the past eight years. Well, I recently acquired a new camera and decided it was time to bring Deep Groove Mono into the 2020s with a new series, Video Vinyl Spotlight. The first video covers Blue Note’s 80th Anniversary reissue of Larry Young’s Into Somethin’. Feel free to head over to YouTube and subscribe to my channel if you haven’t already, and stay tuned!

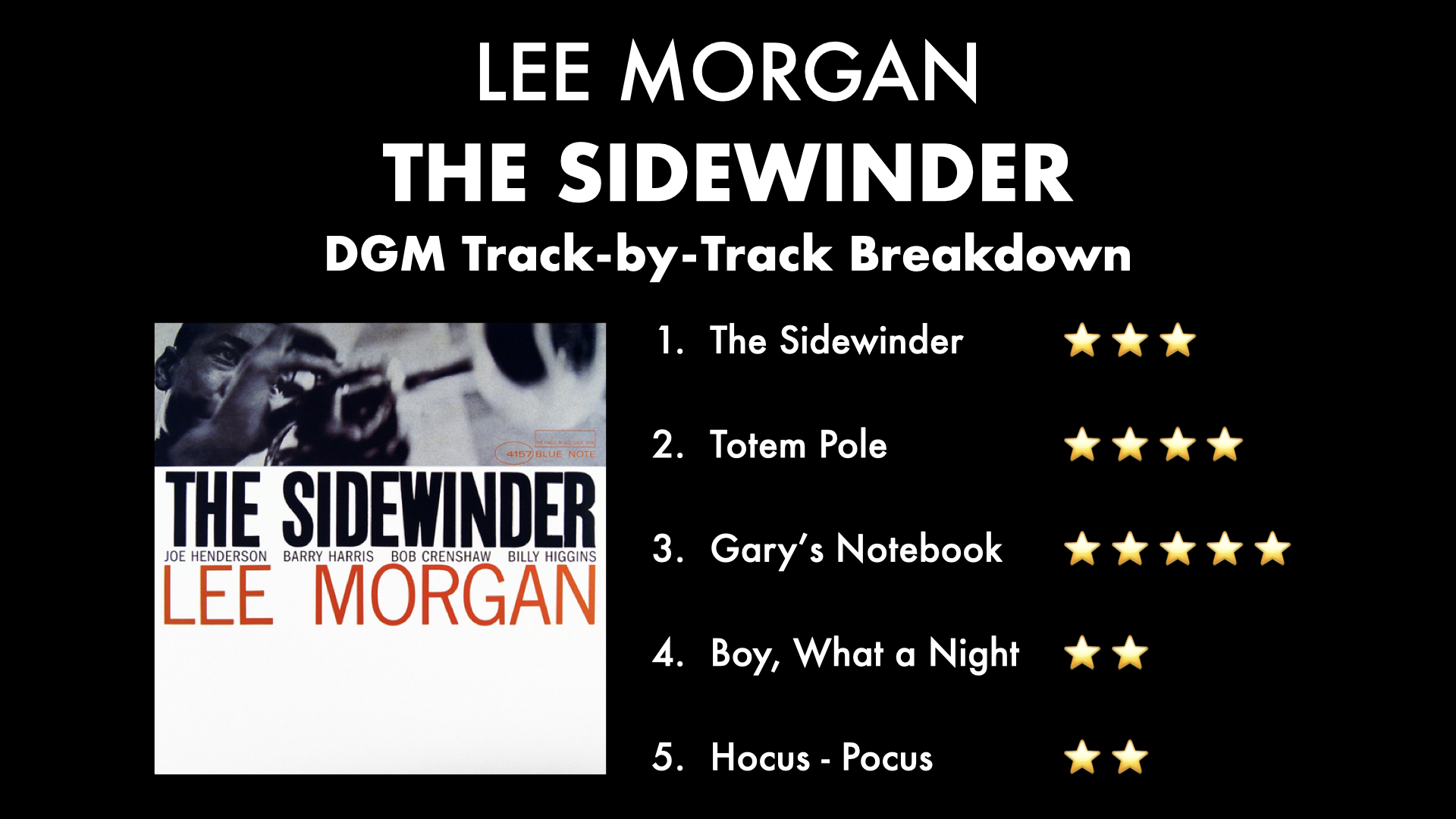

The Deep Groove Mono Classic Jazz Album Art Extravaganza

Ladies and gentlemen, after several unexpected weeks immersing myself in images and history, I present to you the Deep Groove Mono Classic Jazz Album Art Extravaganza! This design love fest has been broken into two parts with links below. The first is an essay on Modern American design and its origins, and the second is an extensive gallery that includes commentary on each cover from yours truly. This project started small and turned into something much bigger, I am exhausted, and I hope you don’t mind if I let the content do the rest of the talking!

LINK: Jazz Album Art and the Origins of Modern American Graphic Design

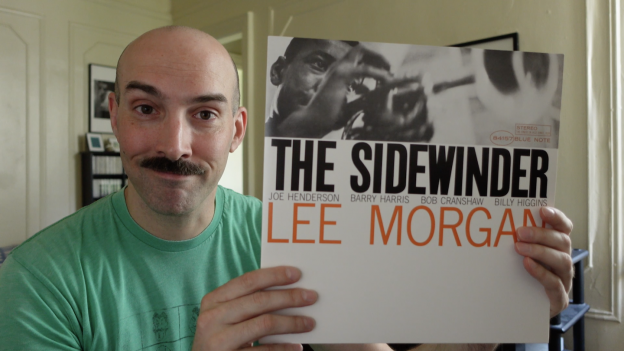

Shellac Spotlight: Lester Young, “These Foolish Things” / “Jumpin’ at Mesner’s” (Aladdin 124)

Original 1946 pressing

Recorded December 1945 in Los Angeles

| A | These Foolish Things | |

| B | Jumpin’ at Mesners’ |

Selection:

“These Foolish Things” (Strachey)

God knows why these Aladdin 78s are so cheap because they are a goldmine of fantastic performances by Young and his various company. For the 1945 session that produced this particular disk, Young’s quintet included pianist Dodo Marmarosa and trombonist Vic Dickenson, the latter of which sits out the A-side, “These Foolish Things”. This is a standard ballad that Lester Young owns like a Cadillac paid for up front with cash. Before I had a chance to study Young in even the most rudimentary of ways, I had heard more experienced jazz fans talk about his breathy style of playing. Once I started listening for myself, that breathiness quickly proved an undeniable hallmark of Prez’s sound. He has one of the most original tones in the history of jazz, and it’s something that makes him instantly recognizable.

Of course, listening to classic material like this just sounds right on 78. The soft, consistent surface noise complements the mood. I also own the CD box set of these Aladdin recordings, and though my regular readers will know all too well how much I love the dead-accuracy of digital — especially for older lower-fidelity recordings like this — I find myself listening to my needledrop of the 78 far more than my CD rip. Make no mistake about it, though: the box set, produced by Michael Cuscuna, delivers with startling clarity and low noise. Yet I still seem to prefer listening with all the extra “stuff” baked in to the 78 experience.

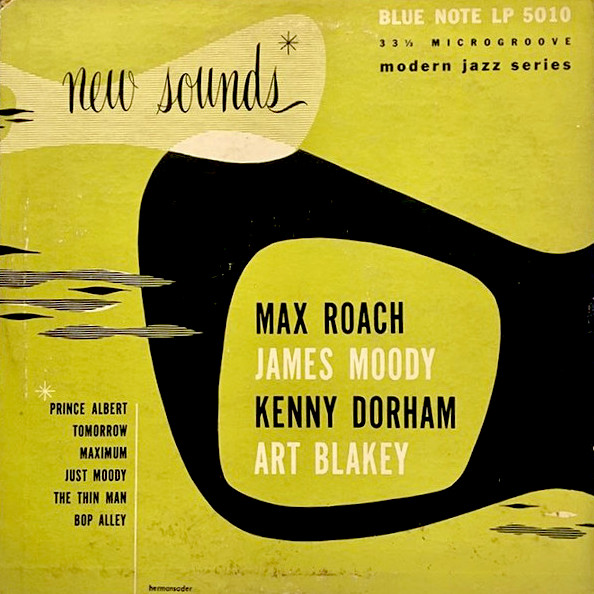

Shellac Spotlight: Max Roach Quintet, “Maximum” / James Moody Quartet, “Just Moody” (Blue Note 1570)

Original 1949 pressing

“Maximum” recorded May 15, 1949 at Studio Technisonor, Paris

“Just Moody” recorded April 30, 1949 in Lausanne, Switzerland

| A | Max Roach Quintet, “Maximum” | |

| B | James Moody Quartet, “Just Moody” |

Selection:

“Maximum” (Dorham-Roach)

The A-side, “Maximum”, steals the show by a longshot. It was written by Max Roach and Kenny Dorham, and the title is surely a tribute to the former. I would be hard-pressed to find a more exhilarating musical performance in any era and in any genre of music. Indeed, Max Roach played a central role in making fast tempos fashionable during the bebop era. I have always been fascinated by how quickly bop is played at times, and several years ago I actually set out to determine which drummers in jazz could play the fastest. At the end of my survey, Max Roach and Tony Williams were at the top of the heap, unmatched in their ability to keep a steady, swift beat.

This track is of incredibly-low fidelity standards. But just like the other 78s covered here recently, that lack of sheen gives the recording oodles of character. In fact, I’m glad this wasn’t recorded in higher fidelity — can you imagine how different the overall feel would be if this was recorded at 30th Street in the 1960s? Bassist Tommy Potter gets lost in the lo-fi melee but everyone else cuts through with ease. Perhaps as a consequence of being the session leader, and despite the trend to subdue the drummer in 1940s recordings, leader Roach has a surprisingly up-front presence. This rightfully gives the sonic spotlight to Roach’s pedal-to-the-floor tour de force.

I have never heard such thunderous drumming in my life. Roach’s in-your-face snare packs a punch, and when he winds up for one of his machine-gun fills, watch out. (Depending on how you count a measure, and as a result of how fast the song is, Roach is technically only playing eighth notes during these rolls!) Solos by James Moody, Dorham, and Al Haig are all executed with astounding precision, all the more impressive when considering the quintet’s race-car velocity. But my god, Roach is superhuman on this. He is incredibly inventive, even while comping, and his accuracy is awe-inspiring.

Max and company recorded four other tunes on that Paris spring day in 1949. All five were released in the 78 format by Vogue Records in France originally. “Prince Albert”, “Maximum”, and “Yesterdays” (titled “Tomorrow” for this issuing) would all be licensed to Blue Note for 78 release before they appeared on Blue Note ten-inch 5010 three years later. “Baby Sis” (dubbed “Maxology”) would be licensed to Prestige Records for a 78 release here in the states, and “Hot House” (titled “Ham and Haig” — someone dodging publishing royalties???) would remain unissued in the U.S.

|

Nothing beats feeling the sheer weight of a shellac 78 in your hands. I have a special adoration for the original Blue Note 78 label as well. This precursor to the classic Blue Note LP label is perfect in every way. I love the thicker block font of the company name and how everything fits neatly within in the 78 label’s smaller surface area. I also like how the deep groove lines up with the edge of the label as originally intended. The hazy yellow — preceded and succeeded by the more familiar off-white — has an edginess, though I wonder if this was an intentional aesthetic choice despite the fact that many Blue Note 78s look like this.

|

| Getting ready to (gently) drop this record on my turntable |

Disks like this make record collecting worth it, and I’m glad to have stumbled upon this record when I did. Episode 2 of Origins of Bop is slated for next week so stay tuned.

Origins of Bop: Charlie Parker / Miles Davis, “Ah-Leu-Cha”

Charlie Parker, “Ah-Leu-Cha” (Original 78)

Savoy Records Cat. No. 939 (Side B) | 1948

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- Charlie Parker, alto saxophone

- John Lewis, piano

- Curley Russell, bass

- Max Roach, drums

Miles Davis, “Ah-Leu-Cha” (Original LP)

Columbia Records Cat. No. 949 | 1955

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Red Garland, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

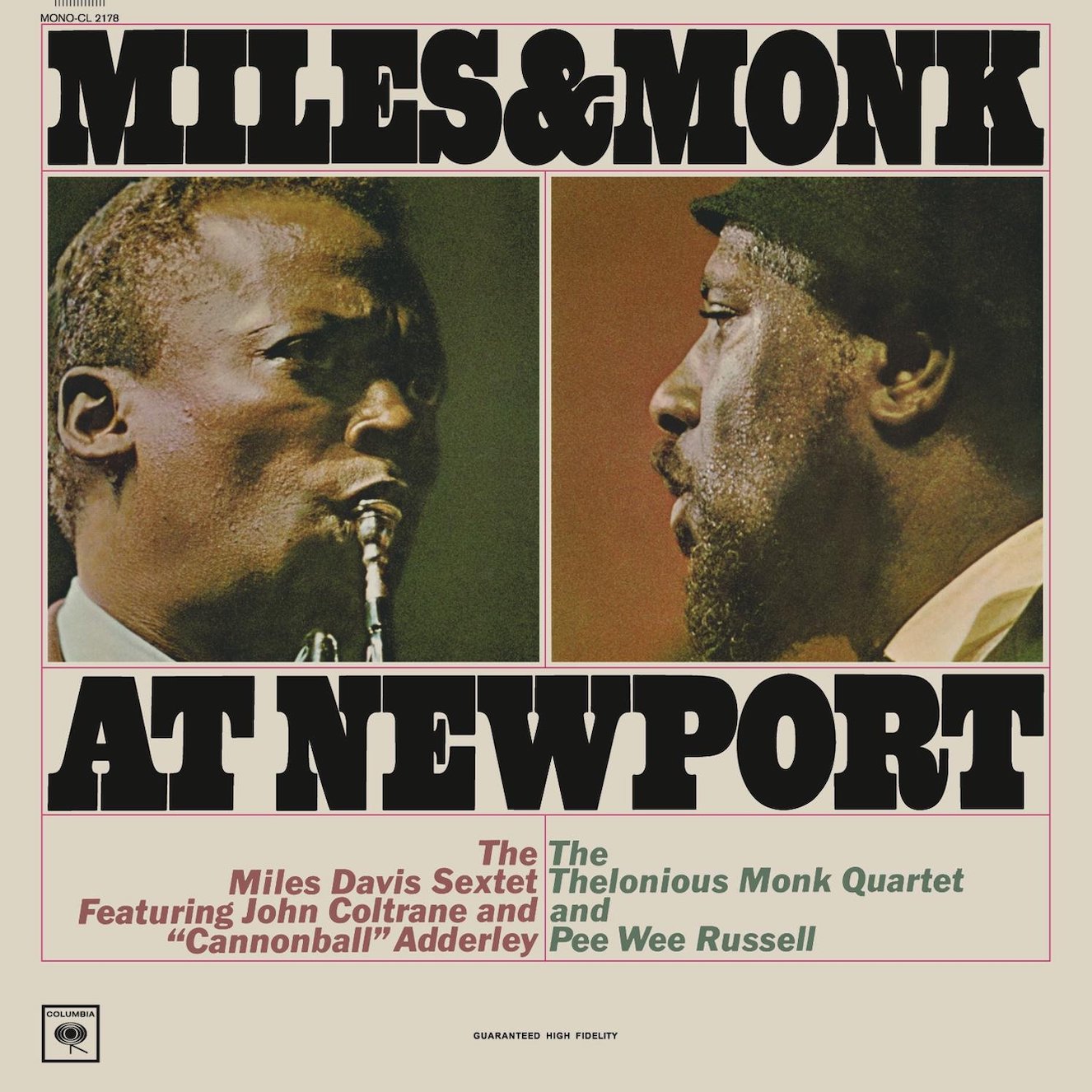

This first installment features a tune composed by one of the founding fathers of bebop. I was introduced to Charlie Parker’s “Ah-Leu-Cha” back in 2001 through the first jazz LP I ever bought: Miles & Monk at Newport. One rainy afternoon in Albany, New York I had a break between my college classes, so I decided to hop in my car and venture downtown to Last Vestige, a local record shop. With a musical background largely focused on hip hop and rock at the time, my experience with jazz was limited. All I had was a cassette tape from a friend with Kind of Blue on one side and My Favorite Things on the other. But as a DJ, I had been seeing lots of cool covers for jazz albums popping up on the Turntable Lab website, and I had recently gotten interested in Madlib’s new electronic jazz project, Yesterday’s New Quintet. I was also DJing with an R&B cover band, and I befriended the group’s saxophonist, who was a locally-renowned jazz musician and composer.

|

| My first-ever jazz vinyl purchase |

This all had an influence on me when I decided to check out the jazz section of that shop for the first time. The copy of Miles & Monk I found was a stereo ‘70s reissue, it costed six dollars, and I pretty much bought it solely on the strength that I had heard of both leaders before. Side 1 was the Miles side. “Ah-Leu-Cha” was the first track, and it wasted no time ripping my face off. Miles liked to play fast live, and this Newport Festival reading was taken at a blistering pace, nearly twice as fast as Parker’s original 1948 recording, which by no coincidence also featured Davis. If I’m being honest, I remember wondering if I would even like jazz if this was what most jazz sounded like! Today I love that recording for its tenacity, high fidelity, and airtight performances. But back then, knowing nothing about jazz and being quite unfamiliar with such high levels of musicianship, I felt utterly confused.

Many years later when I discovered Davis’ classic ‘Round About Midnight, I was pleasantly surprised to find a slower, more accessible version of “Ah-Leu-Cha”. It was recorded three years before the Newport date in 1955 and features Miles’ First Great Quintet. Philly Joe Jones sounds snappy, his patented loose-wrist cymbal work creating an inimitable groove for each soloist to work with. The exceptional fidelity of this recording needs to be noted as well.

|

| Side 1 label for CL 949 |

Prior to reviewing ‘Round About Midnight for my blog several years ago, I had never noticed Parker as the composer of “Ah-Leu-Cha”, and when I listened to Bird’s version for the first time I was caught off-guard by its syrupy tempo. Recorded for Savoy Records at Apex Studios in New York City (mentioned last week in a blog post here), engineer Harry Smith set the rhythm section back a ways behind a very present front line. This was a standard mixing aesthetic in the 1940s, and it makes jazz recordings from that period unmistakably of-the-era. Max Roach could tear it up like no one else in 1948, but he’s much tamer here. Peppering the backbeat with gentle fills throughout, the drummer manages to quickly trade two half-bar solos with bassist Curley Russell before the track’s closing. As a composition, the counterpoint of Bird and Miles creates exciting harmonic motion that makes my ears smile every time I hear it.

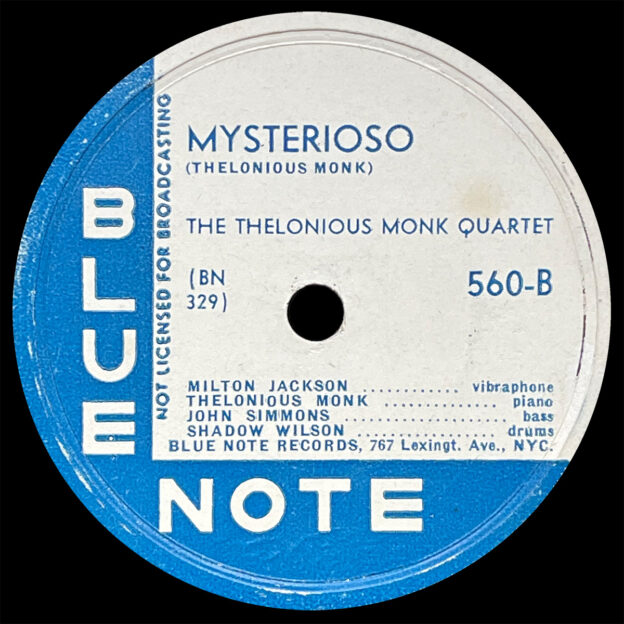

Shellac Spotlight: Thelonious Monk, “Humph” / “Misterioso” (Blue Note 560)

- Original 1949 pressing

Personnel:

- Idrees Sulieman, trumpet (side A only)

- Danny Quebec West, alto saxophone (side A only)

- Billy Smith, tenor saxophone (side A only)

- Milt Jackson, vibraphone (side B only)

- Thelonious Monk, piano

- Gene Ramey, bass (side A only)

- John Simmons, bass (side B only)

- Art Blakey, drums (side A only)

- Shadow Wilson, drums (side B only)

“Humph” recorded October 15, 1947 at WOR Studios, New York City

“Misterioso” recorded July 2, 1948 at Apex Studios, New York City

| A | Humph | |

| B | Mysterioso |

Selections:

“Misterioso” (Monk)

“Humph” (Monk)

The recording I am speaking of, a recording that makes my heart melt every time I hear it, is Monk’s original 1948 recording of “Misterioso”, the pseudoword title taking on the more predictable spelling “Mysterioso” for this inaugural release. Eight months prior to cutting this side for Alfred Lion and Blue Note Records, Monk recorded a flurry of tunes in his studio debut as a leader in the fall of 1947, also for Blue Note. But while all three of those sessions took place at a studio operated by WOR radio station in Manhattan, Blue Note pivoted to acclaimed engineer Harry Smith (not to be confused with the legendary 78 collector of the same name) and his nearby Apex Studios for this July 2, 1948 session.

In the late ’40s, Harry Smith was making a name for himself as a major industry player. Yet the fidelity of Monk’s sole session at Apex stands in stark contrast to the earlier WOR dates. The latter, recorded by engineer Doug Hawkins, exhibit lower noise and greater clarity in definition of the instruments. But Smith’s take on this quartet, distorted peaks and all, is dirtier, it’s grittier, and it excels at complementing Monk’s obtuseness both as composer and improviser.

Monk can’t help but demand our attention from start to finish on “Misterioso”. Vibraphonist Milt Jackson, another one of the jazz world’s rising stars at the time, accompanied Monk on the date. While Jackson navigates the changes, Monk manages to steal the spotlight out from under Bags’ busy hands with a jarring, minimalist comping technique that probably struck many contemporary listeners as…odd. For this author listening over 70 years later, it evokes an image of Monk leaning back on his stool between key strikes in a way that might seem casual or just flat-out lazy. But even and especially in the summer of 1948, Monk is hungry. He is a predator on his way to the top of the musical food chain, and in those silent moments he is surely scanning the keyboard with intense focus, deciding which keys will be his next tonal prey. He is a complete and utter alien to the music world, and we have Blue Note producer Alfred Lion to thank for blessing us with this glimpse of just what a musical revolutionary Monk was early on in his career.

When Jackson’s solo is over, the less-is-more trend continues, and the space Monk leaves between notes gives us a chance to catch a glimpse of John Simmons’ bassline lurking mischievously in the background. Long descending runs are often found in Monk’s solos at this time, and his patented half-step dissonance is also on full display. To most of the era’s critics, this flat-fingered striking of adjacent keys was presumedly the work of a hack pianist with poor technique that lacked the necessary precision. Yet time has revealed to us that every last one of these notes was deliberately chosen by a highly skilled pianist with an entirely unique musical conception.

The A-side, “Humph”, is no slouch either. Recorded during the first of the three previous sessions, it stands far apart from “Misterioso” not only in sonics but also in arrangement and songwriting. In fact, one might even guess that producer Alfred Lion was desperate to pair Monk’s strange “B” with a brighter, more upbeat “A” — anything vaguely resembling something more accessible to the customer — and to think that “Humph” was as close as Lion would get is a hilarious predicament only Monk could create.

Like many of the quintet and sextet sides he recorded as a leader at this time, Monk respectfully falls in line with his sidemen on “Humph” by taking a shorter solo that gives everyone a chance to shine under the limitations of the format. A lesser-known original of which Monk only recorded once, “Humph” is a complex undertaking densely packed with descending chords and fast-paced notes that sound like a tornado ripping through a cartoon town. And the peculiarity of that metaphor speaks perfectly to the character of the song’s tumultuous, colorful creator.

RVG Legacy: Preserving the Legacy of Rudy Van Gelder

|

| (Photo credit: Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images LLC) |

It is with great pleasure that I announce the launch of RVG Legacy, a new website dedicated to preserving the legacy of Rudy Van Gelder. Since the pandemic has taken away all opportunities for me to give my presentation on Rudy in person, I decided to build a website that would essentially deliver all the content of my talk virtually. In the spring I wrote the narrative, then over the summer I put everything together and developed the site.

Produced in association with Van Gelder Studio and Estate, RVG Legacy features dozens of never-before-seen photos from Rudy’s personal collection, and it is sure to become the definitive one-stop destination for all things Van Gelder. Check out the promotional video below and have fun exploring the world of Rudy Van Gelder!

Vinyl Spotlight: Toshiko Akiyoshi, Toshiko Meets Her Old Pals (King Records)

- Second Japanese pressing ca. 1974 with “SKK” catalog number

- Originally released in Japan 1961

Personnel:

- Toshiko Akiyoshi, piano

- Sadao Watanabe, alto saxophone

- Akira Miyazawa, tenor saxophone

- Masanaga Harada, bass (all but “Donna Lee” and “Quebec”)

- Hachiro Kurita, bass (“Donna Lee” and “Quebec”)

- Masahiko Togashi, drums (“So What” and “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”)

- Hideo Shiraki, drums (“Donna Lee” and “Quebec”)

- Takeshi Inomata, drums (“Old Pals” and “Watasu No Biethovin”)

Recorded March 7-8, 1961 at Suginami Koukaido (Suginami Public Hall), Tokyo and March 27, 1961 at Bunkyo Koukaido (Bunkyo Public Hall), Tokyo

| 1 | So What | |

| 2 | The Night Has a Thousand Eyes | |

| 3 | Donna Lee | |

| 4 | Quebec | |

| 5 | Old Pals | |

| 6 | Watasu No Biethovin |

Selections:

“So What” (Davis)

“Quebec” (Mariano)

Seems like a fairly shortsighted opinion rooted in some sort of stereotype, but I think there’s ample evidence on Toshiko Meets Her Old Pals that the Japanese can play, and yes, some of them can clearly swing too. I was introduced to this album through Instagram’s @tallswami. He brought it to a jazz collector meetup at my apartment one night. Being that Swami a.k.a. Clifford is in the habit of bringing rare avant-garde to my place, my ears perked up when I heard hard bop coming through the speakers.

For Audio Engineering Nerds

Above all, I was immediately and utterly floored by the fidelity of this recording. The realism and detail is incredible, especially for 1961. The piano breathes and the tightly-tuned drums snap. Recorded in Japan, the wider spread of the instruments reminds me a little of several legendary American recording engineers including my favorite, Mr. Rudolph Van Gelder, and while I normally prefer the more ‘colorful’ sound coming out of Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio at this time, it’s hard to deny the jaw-dropping brilliance of more ‘accurate’ recordings like this.

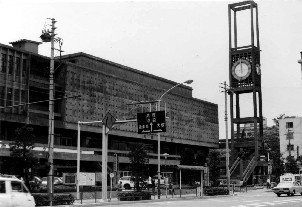

Toshiko Meets Her Old Pals was recorded in two public halls in Tokyo, one of which was renovated and reopened in 2006 (Suginami), the other, according to Discogs, was demolished in 1977 before a new Civic Hall was built on the same site with the same name (Bunkyo) in 1994. The favorably dry sound of this recording leads me to speculate that either significant acoustic treatment was used in a more cavernous space or the album was recorded in smaller, less reverberant rooms…perhaps a combination of both.

|

| The original Bunkyo Public Hall, Tokyo (via Discogs) |

For Collectors

I was debating between seeking out this 1974 stereo pressing on King, the original label, and a compact disc reissue, both products of Japan. Copies of this album in any format are less than easy to come by, especially the LP presented here and especially here in the states. As far as original pressings go, one might prematurely conclude that this album went unissued for over a decade after being recorded (I couldn’t find any evidence of original labels on the web). But careful investigation of Popsike reveals two deep groove copies, one mono and one stereo, sold on eBay several years ago.

Once again the Japanese have provided ample evidence of their vinyl-making mastery: the dead-black background of this pressing’s sonic palette was another thing that won me over the first time I heard it. As a result, I had it on my radar for several months with nothing in sight. Finally one popped up in the U.S. of all places, and I was fortunate to find a copy just as lovely as Clifford’s.

|

| What’s not to love about the midcentury design of this building lobby, the bright red, extra-wide OBI, and our leader’s beaming cuteness? |

For Music Lovers

I gather that Toshiko is well-known in the jazz collector community. Perhaps she has an allure that is the result of being different, sort of like the new kid in school. Beyond that, I can’t say I know any collectors who are deeply steeped in her catalog. A ten-inch LP of hers was released on Norgran in 1954, with two releases by Boston label Storyville following in 1956 while she was a student at Berklee (catalog numbers 912 and 918). Then in 1957 her live Newport festival performance was paired (rather oddly) on a Verve split-LP with accordionist Leon Sash. After laying to tape a trio LP for Verve later that year, Toshiko led another studio date in ’58, this time for the Metro Jazz label. Still based in New York two years later, Toshiko was no longer Akiyoshi, having married fellow musician Charlie Mariano, and in late 1960 she recorded Toshiko Mariano Quartet with her new hubby for Candid at Nola Studios.

Then we arrive back here. Rather, she arrived back in Japan after spending a good amount of time in America, and she quickly got to work recording. Toshiko’s first move here is bold, covering “So What”, a new classic all but two years young back in 1961. The band has a tendency to imitate their American counterparts, dodging in and out of moments of gratitude toward the original Kind of Blue session musicians. This tribute-style of playing caught me a little off-guard at first and I wasn’t sure whether to make heads or tails of it, especially with a negative stereotype of Japanese jazz musicians looming overhead. So I tapped Swami for his take. Always a man of few words with understated, deep musical knowledge, Clifford agreed about the band’s referential style but also found it “interesting”. ‘Nuff said.

At the end of side one the band smokes through Charlie Parker’s “Donna Lee”, then upon turning the record over we find the album’s crown jewel, “Quebec”. Composed by the leader’s then-husband Mariano, the tune helps the band find a mellow, slow-burning groove where Toshiko and her pals are at their best. The follow-up is “Old Pals”, an adorable blues penned by Toshiko herself. The rhythm section gets a makeover here as they do throughout but the small-room sound and intimate vibe remain.

Since the recording of this unsung classic, Toshiko has released dozens of albums and remained active as a recording artist up to the present day. And at 90 years old, one can be sure that she looks back on recording experiences like this with smiling eyes.

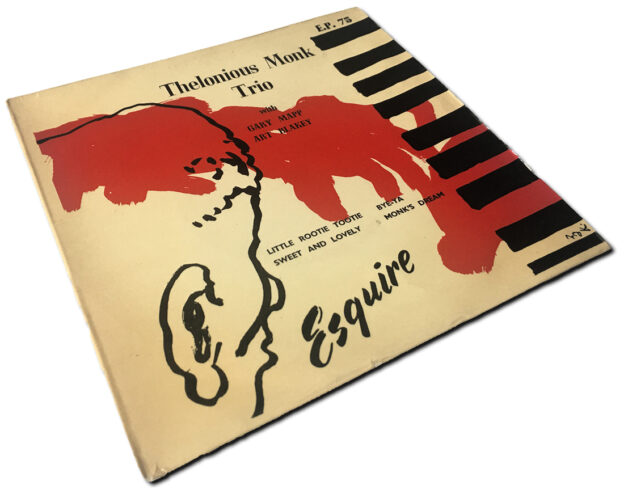

Vinyl Spotlight: Thelonious Monk Trio (Esquire EP-75) Original 45 RPM 7″ EP

Original 45 RPM 7″ UK pressing circa 1954

Personnel:

- Thelonious Monk, piano

- Gary Mapp, bass

- Art Blakey, drums

Recorded October 15, 1952 at WOR Studios, New York, NY

Selection: “Monk’s Dream” (Monk)

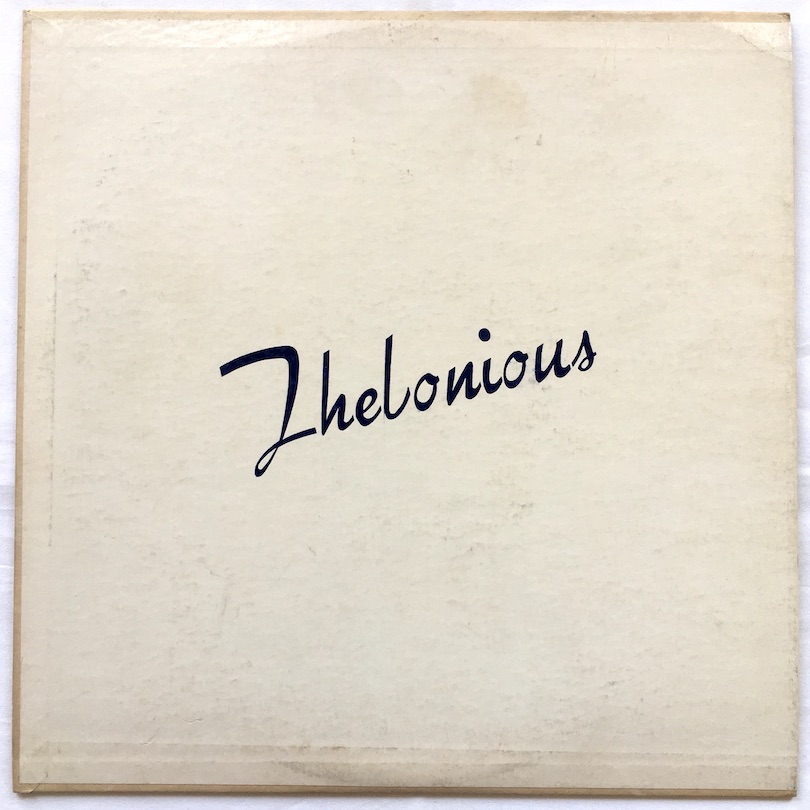

Recorded in 1952, the four sides on this Monk EP were originally issued as two 78 RPM shellac disks and also compiled on a Prestige ten-inch LP, catalog number 142, with the original cover simply reading Thelonious. I owned a copy of the latter at one point: what a gorgeous cover, and at the same time what hissy, wimpy-sounding mastering. Last year when I attended the Jazz Record Collectors’ Bash in New Jersey for the first time, I managed to meet producer and author Bob Porter, who confirmed that the first round of Prestige ten-inchers were generally shoddy. Bob told me a story of a radio jock in Manhattan dialing up Prestige to demand they continue sending 78s to the station in place of the ten-inch LPs.

|

| The original ten-inch pressing of PRLP-142 |

Though the cymbals don’t cut through quite as much as they do on my 2000 Monk Prestige CD box, this Esquire EP is of a much higher fidelity than the original ten-inch. Do I feel that the faster speed of 45 revolutions per minute creates a significant bump in fidelity? Maybe…it would be hard to prove in this case I think. I also find it fairly neat that this EP perfectly compiles all four tracks from Monk’s inaugural recording session with Prestige.

Monk biographer Robin D.G. Kelley has noted that Monk had no choice but to use an old, out-of-tune piano for this session. I can hear the results of that now but I’m not enough of a musician to have heard it before I read Kelley’s book. Perhaps ironically, I think the faulty piano complements Monk’s creaky style of playing perfectly here.

Of all Monk’s work, his Prestige catalog hits a particular sweet spot: hungry performances recorded with fidelity that for the most part improves on the pianist’s previous studio sessions for Blue Note. In 1952 most modern jazz fans would have been unable to hear Monk’s newest compositions played live by their composer in the jazz clubs of New York City. As a result, they got to hear three Monk originals for the very first time with the release of these sides. On “Little Rootie Tootie”, the discordant stomping of keys comprising the chorus screams for the spotlight and is exemplary of a generally raucous session. Though this type of device may sound a little contrived to me today — far from the intricacy of “Monk’s Dream”, for example — it surely had the shock value to entice me back when I was first getting into Monk.

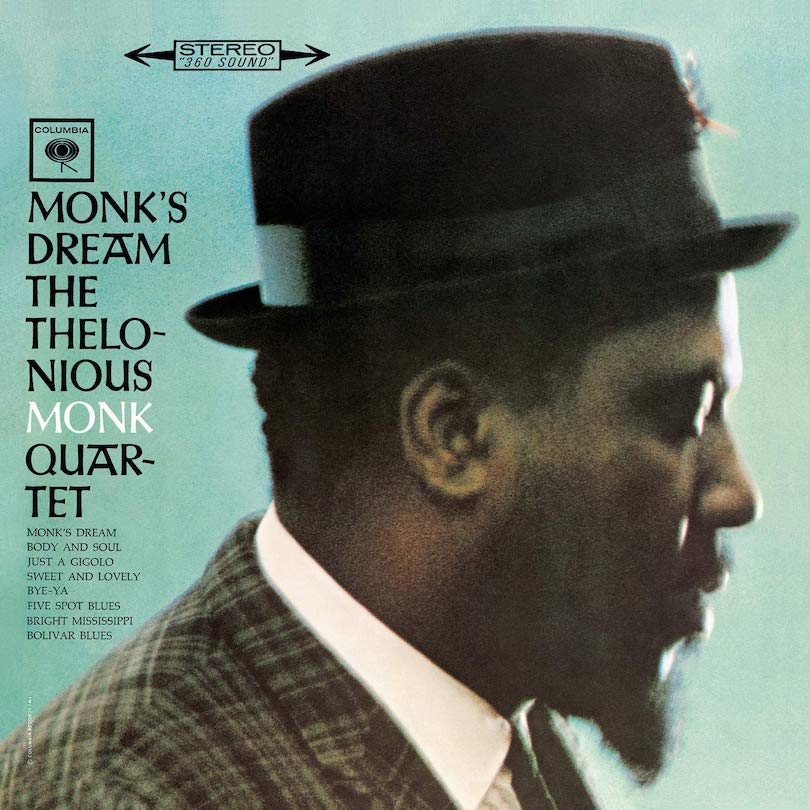

It’s worth noting that the three remaining songs from this session all resurfaced in 1963 on Monk’s first Columbia LP, Monk’s Dream. Like most jazz fans I’m sure, I was introduced to these songs (two originals and one standard) through the Columbia release. If one were to argue that the original Prestige recordings are a more authentic documenting of Monk’s work, it would then be a tragedy that so many jazz fans are introduced to these songs by way of the less aggressive Columbia LP. Aside from the fact that the Prestige session preceded the Columbia sessions by ten years, my personal feeling is that the band’s rawer delivery for Prestige does a better job of personifying Monk.

|

| Monk’s first release for Columbia Records |

That being said, when I heard the Prestige versions for the very first time, I think I probably still preferred the Columbia versions. Perhaps the former was a little too raw for me at first. For example, I definitely preferred the Columbia version of “Bye-Ya” and Frankie Dunlop’s straight-ahead swing over Art Blakey’s calypso beat on the Prestige version. But Blakey’s dirty, overly-compressed ride cymbal crashes and thunderous tom-tom hits have grown on me.

On the Columbia album Monk gives us a rather gentle reading of “Monk’s Dream”, and the dynamic, state-of-the-art quality of the Columbia recording further enhances this softer feel. This starkly contrasts with the Prestige version, where Monk plays more (dissonant) notes and is more unhinged. Again I was taken aback by this less harmonious sound initially, but over time I have come to adore it. Sandwiched between the two heads are two choruses of Monk soloing, and the way Monk flips the B-section at both passes demonstrates the pianist’s mastery of rhythm. In the first, Monk winds up with a repetitive trinkling of adjacent keys only to create an impactful sense of resolve when he brings the A-section back in smack on the “one”. The next time around Monk uses a similar motif, building us up with an ascending Chopin-esque run then landing with a swinging return to the “A”.

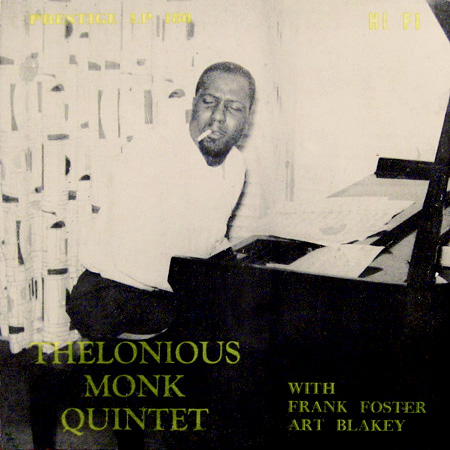

|

|

This is the Monk I think of when I hear these sides: In the zone, raw, and unfiltered |

Monk’s reading of “Sweet and Lovely”, a less obvious standard with publishing dating back to 1931, rounds things out. Though the Prestige version is again packed with harmonic dissonance, it’s the moment on the record where everything settles down a little and the listener gets a much-deserved rest.

Typical of Esquire, and as we have now seen more than once here on DG Mono, the album art for this EP is sublime. Enjoy the audio clip and don’t sleep on Monk’s Prestige years!