For Collectors

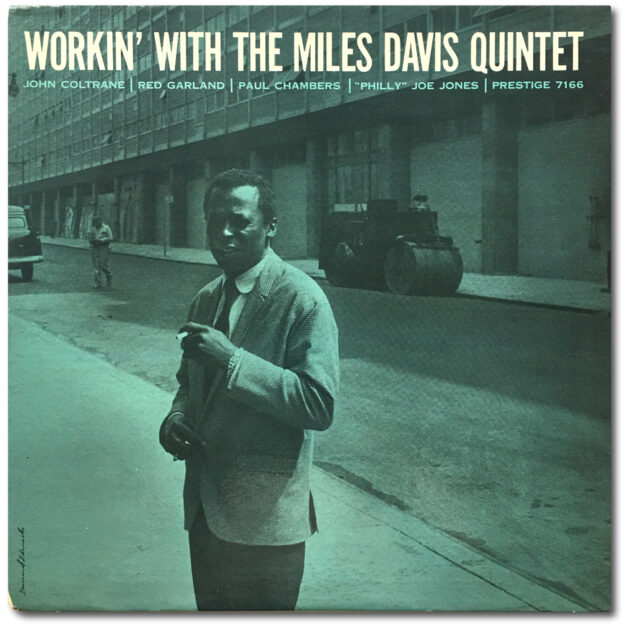

When I first began collecting vintage jazz records, I quickly noticed that Sonny Clark’s Cool Struttin’ is a very in-demand album and considered by many to be a classic. Additionally, I noticed that original pressings fetched in the upwards of two thousand dollars. At some point I became aware that this third/fourth Liberty pressing with original mono Rudy Van Gelder mastering existed, but it still fetched substantial sums of money despite being at least eight years removed from the initial release. Since this isn’t one of my favorite jazz albums, I didn’t foresee myself owning a copy with the Van Gelder stamp any time soon.

Then this copy popped up in a friend’s list of records for sale. Graded highly and priced very fairly, I replied to my friend’s email the instant I saw it, beating out any other potential buyers who also received my friend’s list that evening. Despite this not being a personal favorite, I still fancy the music, the price was right, and it is a great recording that, after finally hearing an authentic mono copy, revealed itself to be even more outstanding than I had already known it to be in stereo.

The stereo version of Cool Struttin’ has been vastly favored over the mono in reissue programs down through the decades, and I have owned the stereo RVG Edition CD for quite some time. Coincidentally, just before I acquired this copy, I was considering either a 2004 Classic Records mono reissue or the 2011 Japanese Disk Union “DBLP” mono reissue. Blue Note albums like this recorded between May 1957 and October 1958 are especially intriguing in mono because they were recorded to both full-track and two-track tape, so mono versions aren’t (shouldn’t be) a “50/50” summation of the two-track tape, as all Blue Note mono LPs following this period are. So while in theory you may not hear a huge difference between an authentic mono version and a stereo version with the channels summed, at least in principle the two versions came from two different master tapes.

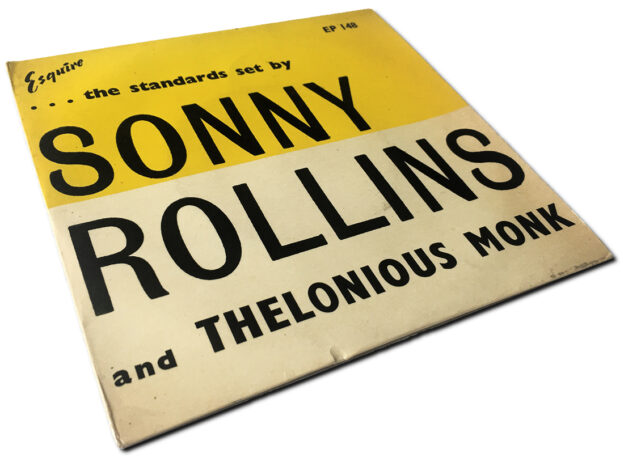

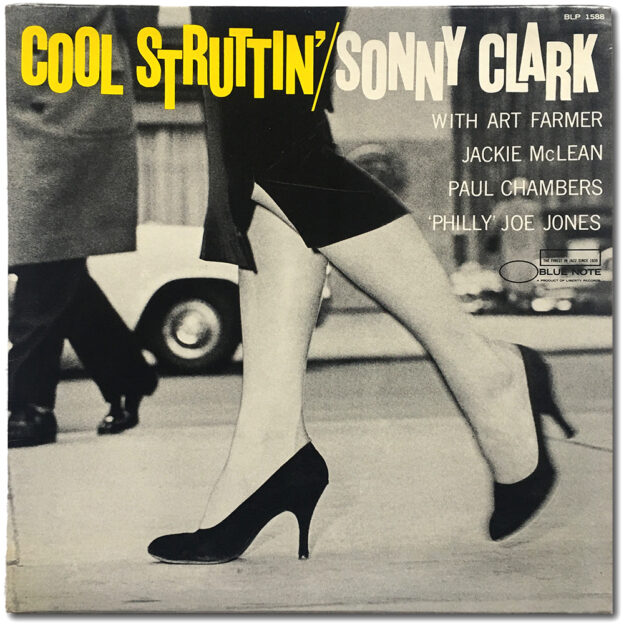

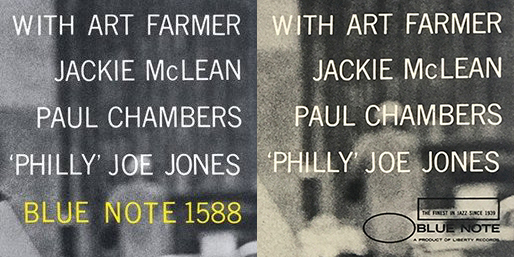

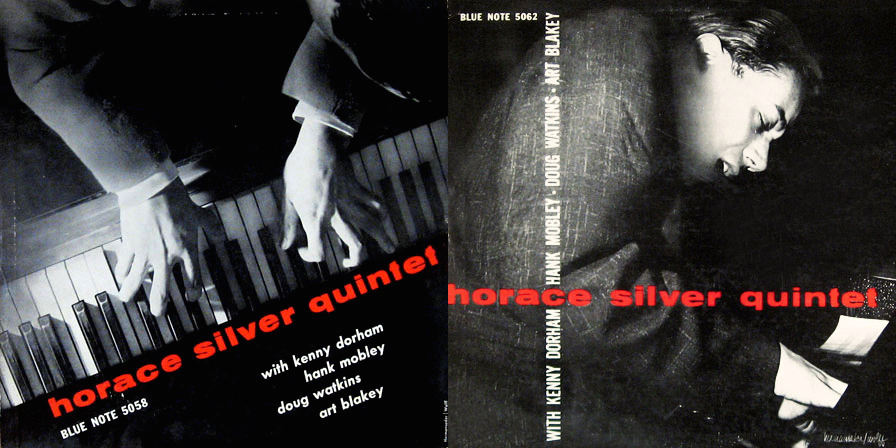

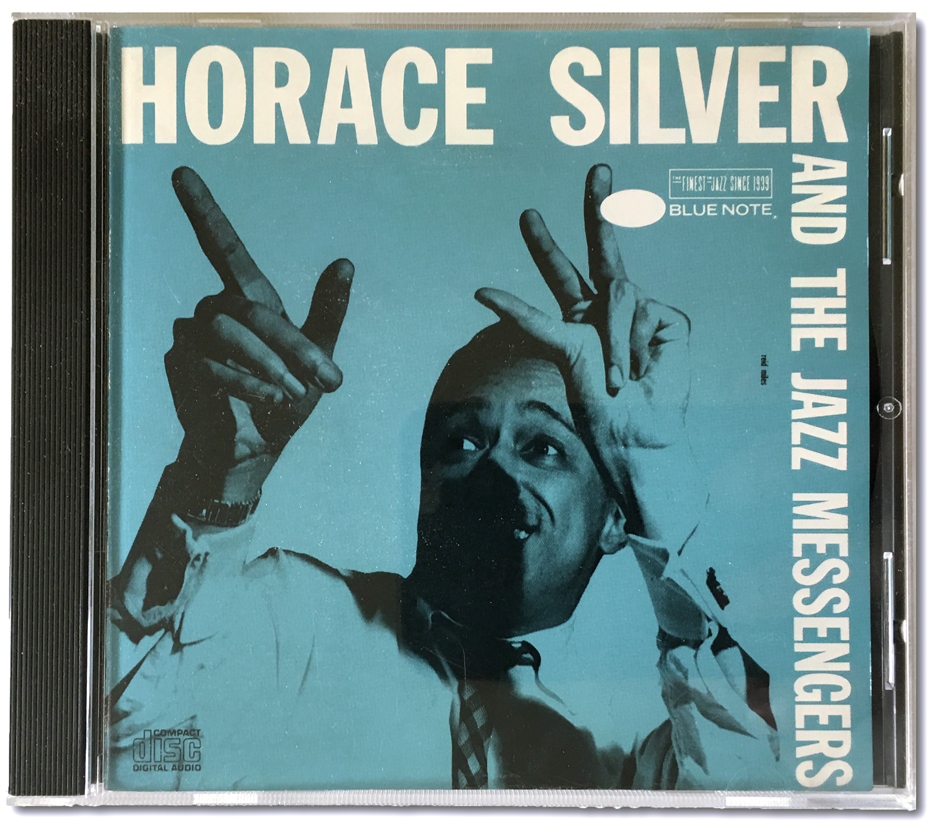

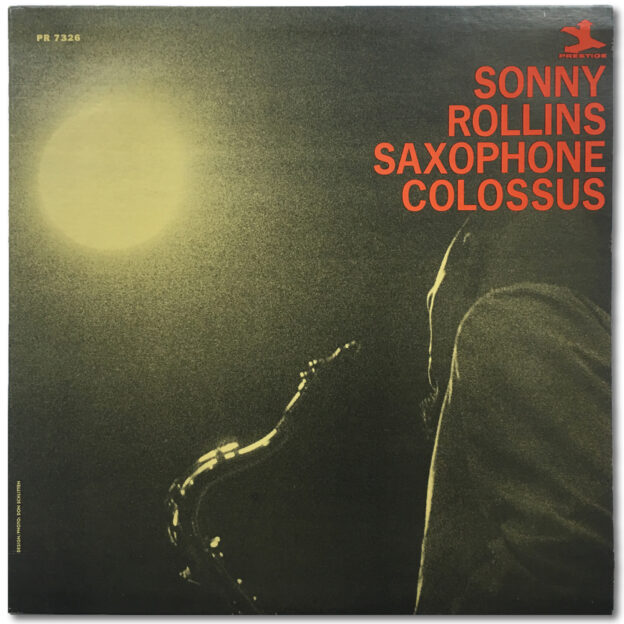

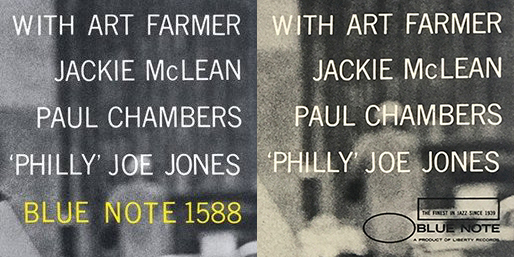

Another factor enticing me to bite on this copy was the album’s iconic cover, which is perhaps the most famous jazz album cover of all time. The presentation of both the graphic and typography remain sharp with this issue, though after Liberty Records acquired Blue Note in 1966 they felt obligated to brandish their name on the front and in the process tarnish Reid Miles’ original artistic vision. The typography he chose for the words “Blue Note 1588” have been replaced with a less attractive outlined version of the label’s note logo complete with the phrase “A Product of Liberty Records” in fine print. While this is the type of thing a detail-oriented collector like myself often takes notice of, it ultimately only amounts to a subtle disappointment that is easy to overlook upon hearing the vinyl’s playback.

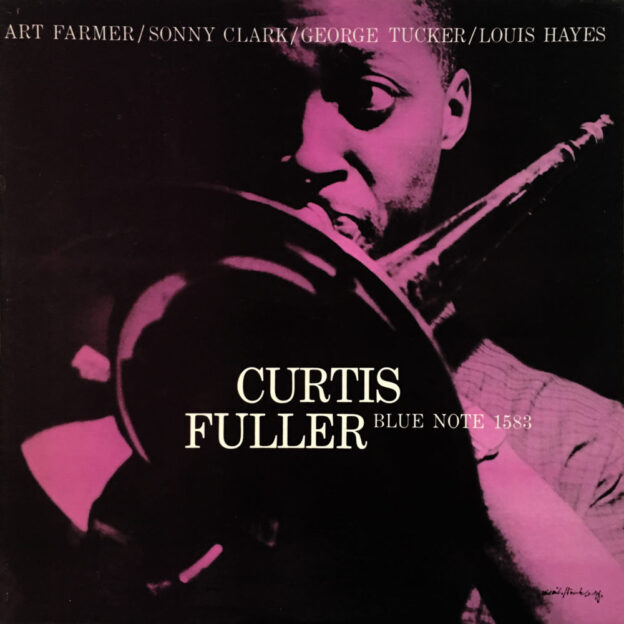

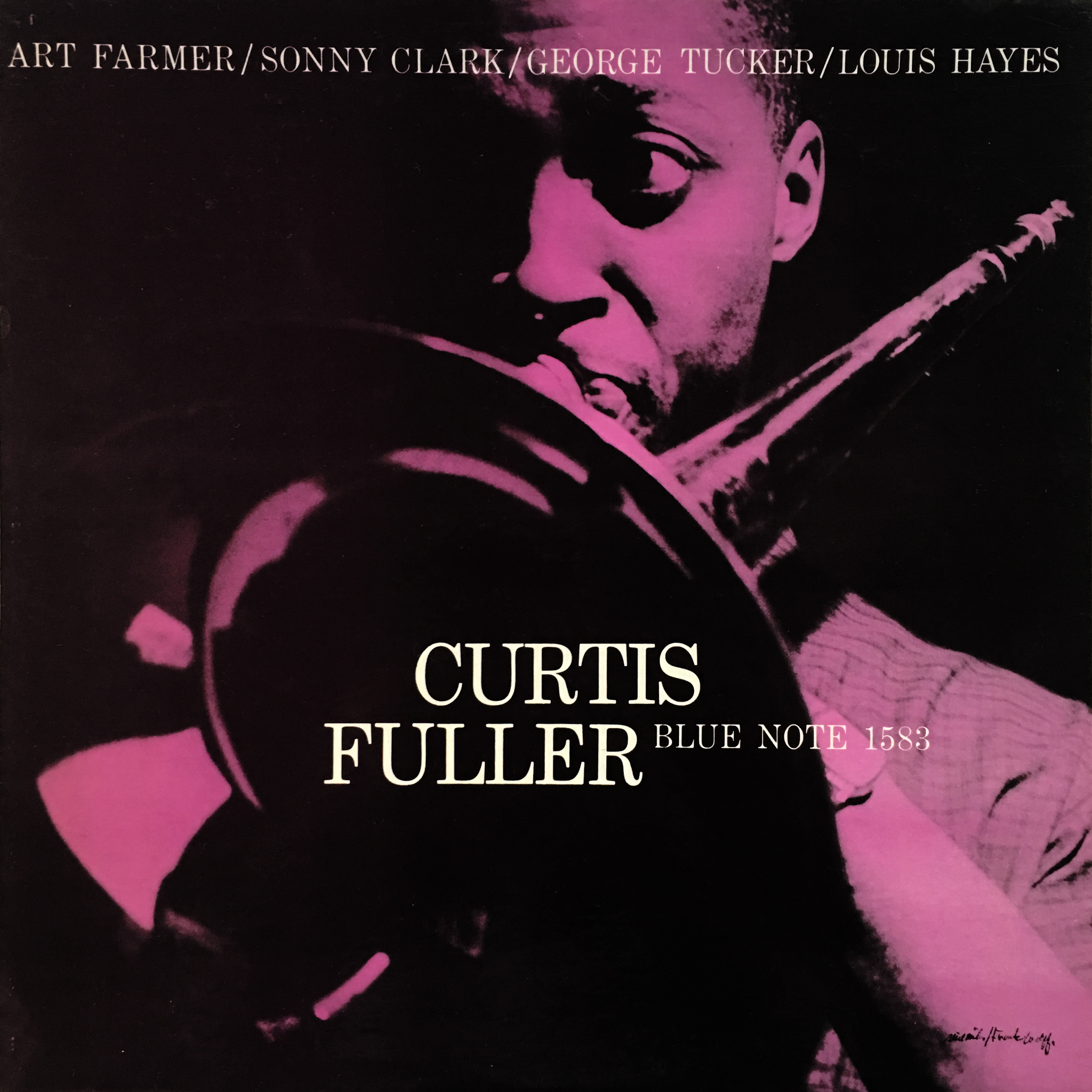

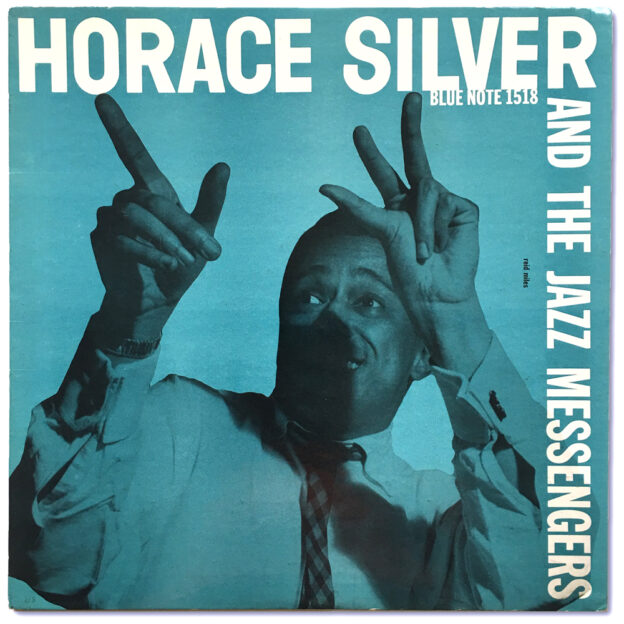

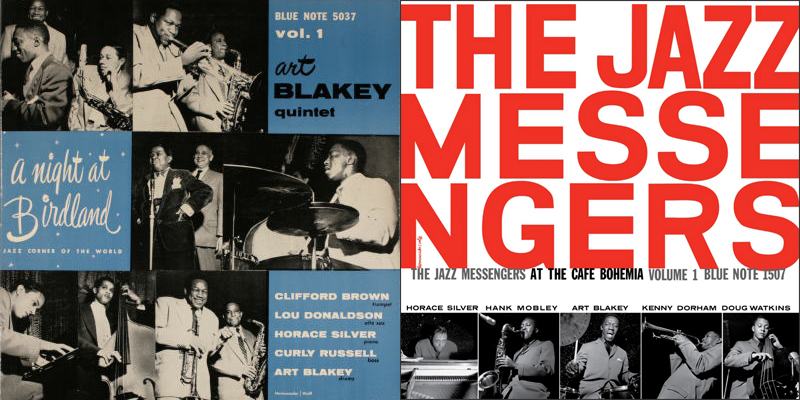

|

| Differences in the original and Liberty reissue album covers |

For Audio Engineering Nerds

The several stereo versions of this album I have heard no doubt have accurate representations of each instrument (save Rudy Van Gelder’s less-than-ideal piano sound, of course), yet the overall presentation has typically been a little on the bright side in stereo, and, as per usual with pre-seventies stereo, sounds disjoint. Surely some jazz lovers prefer the added detail of these stereo mixes; personally I prefer the cohesion of the mono.

I don’t know if my mind is playing tricks on me as a result of this being such a high-profile album, but the mono presentation of Cool Struttin’ seems especially balanced in relation to other mono-stereo comparisons from the same time period. This original Van Gelder mono mastering is on the darker side — especially good here since it sounds like the cymbals were recorded with a lot of high-frequency energy — but everything really locks into place in mono here.

For example, where stereo issues arguably give an added sense of depth by placing the reverb for Art Farmer’s trumpet in the center of the stereo spread with Farmer flanked to the left, on the mono version the same plate reverb melds with Farmer’s tone in a unique and satisfying way. What’s more, the mono seems to emphasize producer Alfred Lion’s artistic sensibilities and engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s ability to give each musician their own sound. As pointed out by my honorable collecting friend Clifford (Instagram’s @tallswami), in contrast to Farmer, Jackie McLean is presented front and center with drier immediacy. These choices emphasize each soloist’s unique character and helps each find their own voice on the recording.

For Music Lovers

Many jazz fans adore Cool Struttin’. While collectors stereotypically have a special fetish for the album that is perhaps in some way informed by its killer album art, a drummer friend who is deeply rooted in the jazz tradition and entirely unfamiliar with the world of collecting has identified this as his favorite jazz album of all time. Paraphrasing him, “It just swings so hard”.

I don’t deny that, but hard bop is my thing and I hear a lot of hard swinging in my day-to-day listening. As a result then, I can’t say that I hold Cool Struttin’ in such high regard. I would never deny that it embodies quality performances by world-class musicians but it’s a bit off-base from my typical taste. I’ve never been a big fan of bluesy walking tunes like the title track; they have always seemed kind of “jammy” to me and hence a bit lacking in purpose. The song’s artistic statements could have probably been made in about two minutes’ less time as well. Not that there’s anything inherently wrong with two solos from a great pianist, but Clark solos twice, and the band seems to be in miscommunication when Chambers comes out of his solo, which leads to an additional chorus of meandering.

I dig the intro of “Blue Minor”, and though the bridge has a cheesy, swanky quality to it, perhaps it creates interesting contrast with the song’s hipper A-section. McLean’s solo here is in the Monkian tradition of sticking close to the melody, but at the same time it sounds out of character for the saxophonist, who is typically quite adventurous harmonically. Ironically, this paints McLean as being somewhat unfamiliar with the tune at the time of recording.

“Sippin’ at Bells” is a Miles Davis composition dating back to 1947, the melody of which has firm roots in the bebop tradition. Regular readers of Deep Groove Mono may be aware that compositions with more complex melodies like this generally aren’t my favorite. True, many Monk compositions I adore have challenging structures (“Four in One”, for example), though there’s something about Monk’s melodies that make them fun to hum regardless (which I believe is a very important aspect of his genius). A lot of bebop melodies make me think of tangled string and thus I have a hard time finding something to latch on to. That said, I don’t feel that “Sippin’ at Bells” squarely falls into this category, and I enjoy both Clark’s take and Miles’ original version with Charlie Parker.

Concluding the album is “Deep Night”, a song originally recorded by Rudy Vallee in 1929 and my favorite track on Cool Struttin’. I love the opening two-minute trio vamp. Philly’s brush work and Clark’s delicate, lyrical style complement each other so well, and Philly’s solo at the end is airtight percussive perfection. I probably would have preferred that the trio finish out the song unaccompanied, but when Farmer and McLean eventually enter they deliver quality solos nonetheless.