It appears that along with a recent change in my philosophy of collecting has also come a change in my luck. I recently decided to go all in on creating the most authentic vintage mono jazz LP listening experience I could. This meant a new turntable (a gorgeous Garrard 301 which I have already secured), a separate component tonearm fitted to a plinth, and the Ortofon CG 25 mono cartridge. But before I could gather all the components for this new rig, an opportunity presented itself to me that I would have been a fool to ignore.

As a result of my change in philosophy, I have worked to put myself in a position where original pressings of my favorite jazz albums are more within my reach financially. Not too long after making this decision, this copy of Lee Morgan’s Candy popped up in a friend’s Instagram feed. “That seems like a very fair price for that Morgan,” was my first text to my friend, sent without any serious intent to buy. But 24 hours later the record was still on my mind, so I worked on my financials and decided I could make it work — if the record checked out — and two days later I made the 90-minute trip upstate on the Metro North railroad to look at the record first-hand and give it a listen.

Once I had it in my hands, the jacket was indeed a strong VG+ with no splits, and the labels were clean with the assumed deep grooves, “47 West 63rd NYC” address, and lack of registered trademark “R”. I listened to the record in its entirety before making a decision. Overall I would have play graded it VG+ with light surface noise that could be heard more during some of the quieter passages, but no loud or repetitive clicks and no distortion from wear. The record came from the original owner, an Upper West Side native who, according to my friend, remembered it as the first record he ever bought.

After making payment, I got on the train home with reserved excitement. I was honestly banking on the noise quieting down after running it through my Spin Clean (one of the greatest dollar-to-value purchases a collector can make, in my humble opinion). After one cleaning the surface noise settled down and I was quite pleased. But after a few plays I wondered if the simple act of playing the LP may have loosened some of the dirt, so why not run it through the machine one more time and see what happens? And I was happy to find that the surface noise had virtually disappeared in many places.

As for holy grails, I’d say Quiet Kenny, Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims, and Overseas are near the top of my wish list, but Candy is really my number one, mainly because I find the entire program to be so great. When I first got into jazz, the atypical arrangement of trumpet quartet stood out to me. I love how playful sounding the music is, and the ballads are some of my favorites of all time.

I think Candy is marginalized by jazz critics for its lack of original compositions, but I could care less when the songs are played with such beauty and brilliant execution. It turns out that most of the songs have their origins in the mid-1940s when Morgan was between the ripe ages of seven and eight. The title track was first recorded by Johnny Mercer and Jo Stafford for Capitol Records and reached number 2 on Billboard’s Best Seller chart in 1945. That same year, “Since I Fell for You” was written and recorded by Buddy Johnson for Decca Records. “Who Do You Love I Hope” is a lesser known song written by Irving Berlin for Annie Get Your Gun in 1946, and “Personality”, penned by Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke for the play Road to Utopia, also premiered in 1946 with a film starring Dorothy Lamour to follow in 1950.

The remaining two songs completing the tracklist would have been more readily recognized by their respective audiences in 1958. “C.T.A”, the only cut on the album with modern jazz origins, was written by saxophonist Jimmy Heath and first recorded by Miles Davis with Heath on sax for Blue Note in 1953 (according to Miles, “C.T.A.” were the initials of Heath’s then-girlfriend Connie Theresa Ann). “All the Way”, the 1957 Academy Award winner for Best Original Song, was written by Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn for The Joker Is Wild, a film about the life of comedian/singer Joe E. Lewis starring Frank Sinatra. Scroll down to hear a Spotify playlist featuring the original recordings of all of these great songs.

|

Top: Johnny Mercer, Jo Stafford, Buddy Johnson, Irving Berlin, Jimmy Van Heusen, Johnny Burke

Bottom: Dorothy Lamour, Jimmy Heath, Miles Davis, Sammy Cahn, Frank Sinatra |

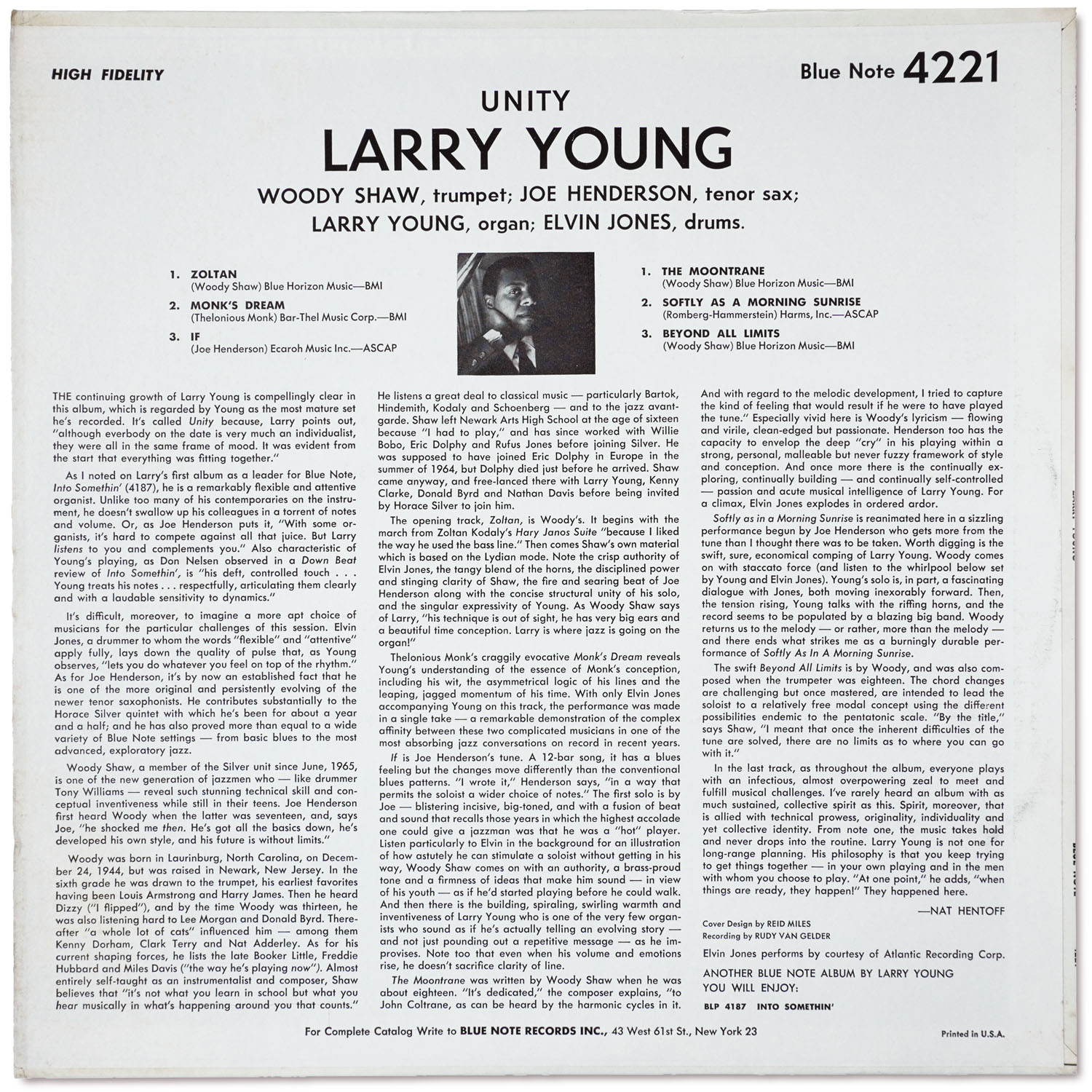

Candy immortalizes the legend of Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack home studio, with the album’s sparse arrangement leaving plenty of room for the sound of the engineer’s living room to make its mark on the recording. Sonny Clark’s piano playing takes center stage here and can be heard with startling clarity, and Art Taylor’s drum kit embodies the gorgeous drum sound Van Gelder would regularly get at Hackensack in the 1950s: a slightly roomy, unified sound with soft cymbals and lifelike accuracy in the bass, snare, and tom toms (for this session, perhaps a little too accurate at times: most collectors are aware of Taylor’s infamous squeaky hi-hat pedal during Clark’s leading solo on the title track).

|

| Morgan dressed to impress while recording Candy in February 1958 at Hackensack |

The mono presentation of the music, while not exclusively found on the original LP, is less than common. In stereo the music sounds as full as primitive stereo can with Lee’s regular presence on the far left of the spread, but the sparse arrangement here never leaves me feeling that the mono presentation of the band is “crammed into the center image”, as critics of the format often object. What’s more, there does appear to be some tape degradation on my stereo 1987 Capitol/Manhattan CD during “Who Do You Love I Hope”, though this is a nonstarter on all mono issues of the album. Apparently Music Matters did find some sort of a two-track “safety tape” of Candy that was in better condition than the old master, and as a result decided to release the album in stereo for their 33 1/3 R.P.M. series after releasing it in mono for their original 45 R.P.M. campaign.

Other interesting variations in the mono and stereo releases of this album include different piano lines played by Sonny Clark for the intro of “All the Way”. The intro of a different take must have been preferred by the team and thus spliced into the full-track master reel by Rudy Van Gelder. Why the two-track reel did not receive similar treatment is testament to the fact that Candy was only released in mono originally, with stereo being a mere afterthought for Blue Note producer Alfred Lion in early 1958. Additionally, the 1987 stereo CD boasts a reading of “All at Once You Love Her” that is noticeably absent from the original tracklist, which I have to believe was a decision made solely as a consequence of the temporal limitations of the LP format.

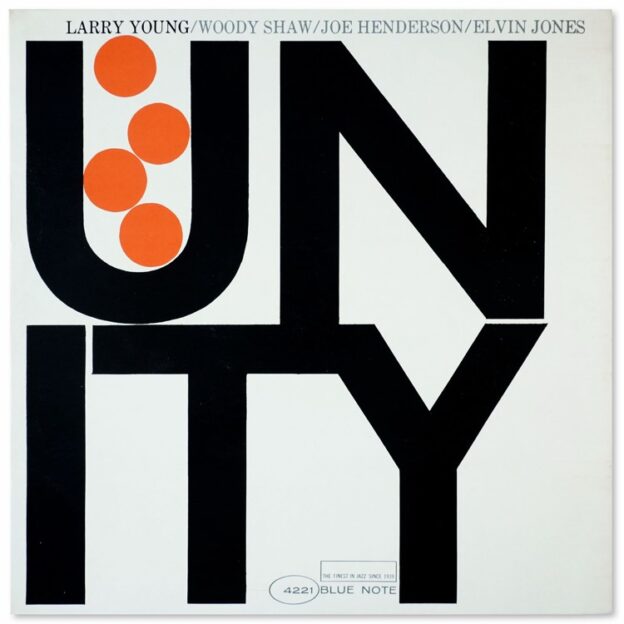

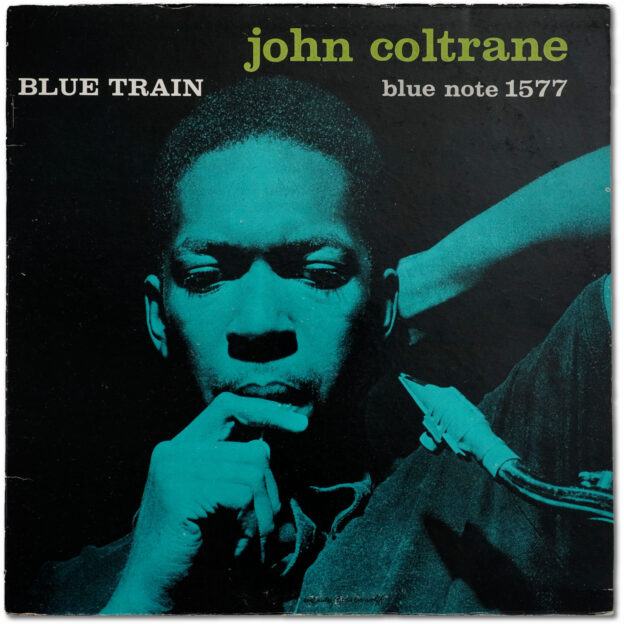

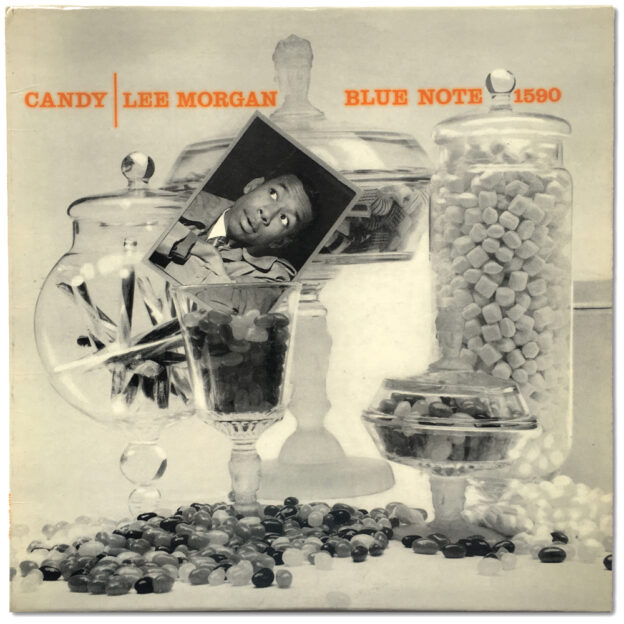

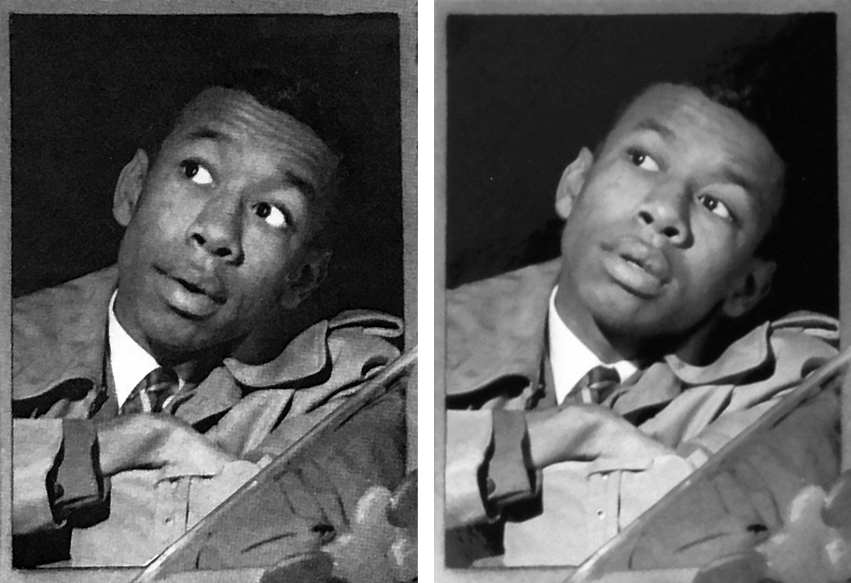

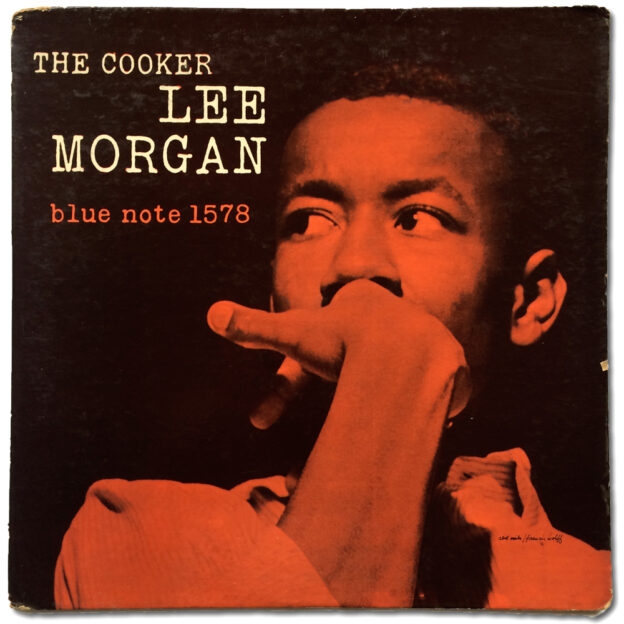

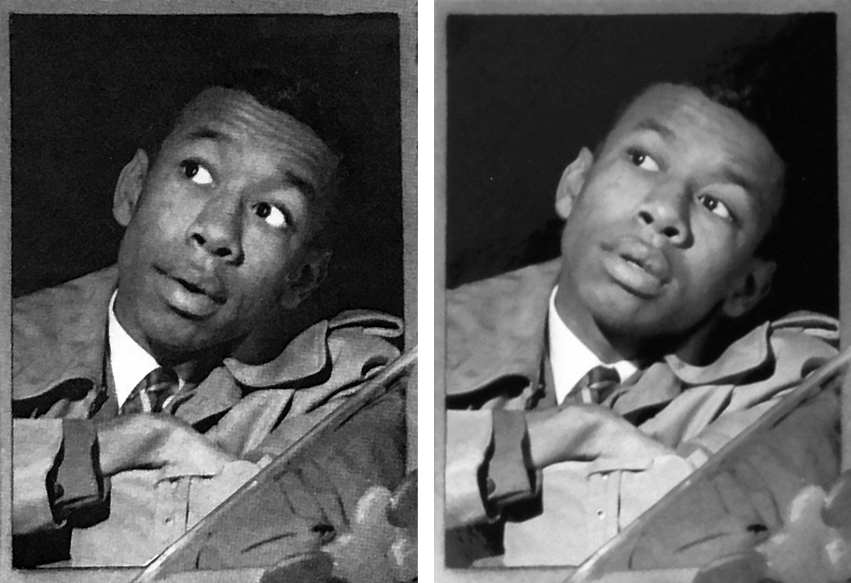

Finally, I admit that I understand when collectors express their distaste for this album cover, but I can’t help but love it. As Lee mischievously glances upward at his name hovering above, the young trumpeter’s boyish innocence conveys a sense of awe toward his newfound fame (side note: though it appears to be a shot from the same sequence of photos as the original, Music Matters used a slightly different photo of Morgan for their reissues). Not being sure why Reid Miles opted to neutralize the potentially explosive rainbow of colored candy pieces depicted here with a black-and-white overlay — perhaps he felt it would be too much of a departure from Blue Note’s two-tone theme — it is a juxtaposition that nonetheless succeeds, with the help of Morgan’s presence, at communicating the playful nature of the musical themes within.

|

| Photos used for the original release (left) and Music Matters reissue (right) of Candy |

When I first started collecting, I gawked at the prices original pressings of this album would fetch, and I would have never guessed I’d be in possession of a copy so early on in my collecting years. So the collector saying goes, music comes first. I have always cherished the gorgeous music presented here, but I can’t deny that listening to an original mono pressing has caused my ears to perk up and listen more intently, specifically to the charming solos of all the instrumentalists. I couldn’t be more satisfied with this acquisition, and this copy of Candy is now, obviously and without question, the crown jewel of my collection.

Spotify Playlist: Songs That Inspired Candy

Note: If you are not logged in to Spotify on your web browser, clicking the “play” icon above will only play 30-second clips of the songs. Click “Play on Spotify” or the Spotify logo to launch the app on your computer. Click here to open this playlist in your web browser.