- Original 1954 pressing

- “767 Lexington Ave NYC” on both labels

- Deep groove both sides

- Plastylite “P” and “RVG” etched in dead wax

Personnel:

- Dave Burns, trumpet

- James Cleveland, trombone

- Frank Foster, tenor saxophone

- Danny Bank, baritone saxophone

- George Wallington, piano

- Oscar Pettiford, bass

- Kenny Clarke, drums

Recorded May 12, 1954 at Audio-Video Studios, New York City

Originally released November 1954

Selections:

“Baby Grand”

“Summertime”

“Festival”

For Collectors and Engineering Nerds

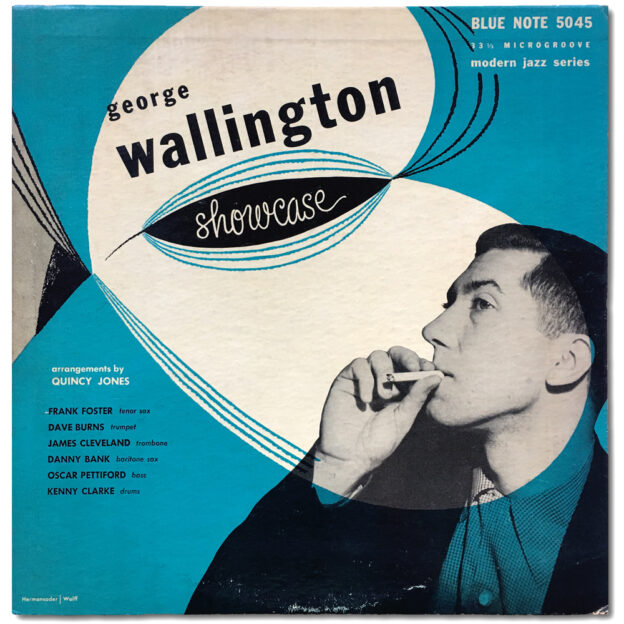

I am fascinated by the extent to which even a mere encounter with an original pressing of a jazz record can heighten my interest in the music. My first experience with classic Blue Note LPs came by way of the Blue Note album cover book and later the website Vintage Vanguard, hosted by what is assumed to be a Japanese collector who has long owned every Blue Note LP in the 5000, 1500, and 4000 series. It was then that I first came across the super-hep cover art for this album. Its typography, artwork, and bold teal background — clearly a byproduct of the early modern art movement of the early 1950s — was a style unlike the minimalist design and sans-serif fonts of Reid Miles’ later work for the label. Although I have grown to adore the ways in which the former style contrasts with the latter, it was an aesthetic that took some time to warm up to. Through all this, I couldn’t begin to imagine a cooler looking cat than Wallington as he appears on this cover. Cigarette in hand, the septet leader was 29 at the time of recording but somehow manages to not look a day over 19, his crew cut and small-check shirt a proclamation of his “in-ness”.

A rare album in any format, I kept it on my radar for many years simply on the strength of the cover art without having ever actually heard it. That changed when I saw an original pressing on the wall of a local shop last summer. It looked clean and the price seemed fair but it still made me proceed with caution. When I got home later I scoured the web for sound clips. Nothing on Spotify, but a few songs appeared sporadically on YouTube. Though I’m not usually a fan of bigger bands, I gave this album a chance and it grew on me after several listens. But when I went back to the store the next day to audition the record, I found a series of loud ticks in one spot so I decided it wasn’t worth the (EX) asking price.

Days later I had a twelve-inch Japanese reissue in my hands by way of another local store, and I have fond memories of playing that copy on many late mornings last summer (“Summertime” being the obvious mood-setter). But I never liked the way Michael Cuscuna arranged the track listings on these reissues, the outtakes of which aren’t included at the end of the original program but placed back-to-back with their respective counterparts. Needless to say, this made for repetitive listening away from the turntable so I eventually got my hands on the ten-inch Japanese reissue, which only included the original program.

The story of how I acquired this particular copy is unfortunately not as fun as others I’ve told of late and can be reduced to a single four-letter word: eBay (womp womp). The seller graded both jacket and record VG+. Normally being skeptical of this grade, I noticed that the auction ended on a weekday afternoon and the seller accepted returns so I decided to take a chance. Later that week I emerged victorious for about 60% of my high bid.

When the LP arrived days later, I was pleased to find that it was conservatively graded. There were some marks but it played through most without a sound, and I was floored by the fidelity. The sound was magnetic, and I’ve played it countless times since. The instrument balance is exceptional (Leonard Feather, responsible for the album’s liner notes, was not known to comment on recording quality but here even he agrees). It is also a very dynamic recording, each soloists loudest notes really jumping out of the speaker, and the space it creates sounds very natural with no artificial reverb added.

Though it is one of the earliest Blue Note titles to bear Rudy Van Gelder’s initials in the dead wax (an indication that the LP was mastered by him), it was not laid to tape by the mastermind engineer. Though the label had recorded with Van Gelder as early as March 1952 (BLP 5020, Gil Melle Quintet/Sextet), Blue Note regularly rotated between a few recording studios through 1953. The New York City locations included radio station WOR and a studio run by the obscure Audio and Video Products Corporation, also known as “Audio-Video Studios”. The last time Blue Note recorded at WOR was in November 1953 (BLP 5034, Horace Silver Trio Volume 2), and from that point on the label almost exclusively used Van Gelder with a few exceptions. Aside from this Wallington date, recorded at Audio-Video in May 1954, Blue Note recorded there again in March 1956 (BLP 1513, Thad Jones’ Detroit-New York Junction, and BLP 1543, Kenny Burrell Volume 2). Perhaps there was a leak in the Hackensack roof in March ’56, though I’m willing to bet that the size of the Wallington band forced them out of Van Gelder’s Hackensack living room and into a larger space back in ’54.

Not much is known about Audio-Video Studios. It appears to have been located on the corner of East 57th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, and Oliver Summerlin, co-founder of Pulse Techniques, Inc. (makers of the legendary Pultec EQP-1 equalizer), was an employee or perhaps even owner of the studio as early as 1949 (sources: Horning’s Chasing the Sound and reevesaudio.com). Other than that, I’ve come to realize that the following famous photo of Clifford Brown was taken by Francis Wolff at the studio on August 28, 1953 during the recording of BLP 5032, Clifford Brown: New Star on the Horizon.

|

| Clifford Brown at Audio-Video Studios in 1953 |

For Music Lovers

I became familiar with George Wallington first by acquiring an original pressing of Jazz for the Carriage Trade (Prestige 7032). From there I acquired the Original Jazz Classics CD reissue of George Wallington Quintet at the Bohemia, extremely rare in its original form and originally released by the short-lived Progressive label in 1955. Preceding the others, Showcase was arranged by a 21 year-old Quincy Jones, who met Wallington when they both were playing in Lionel Hampton’s band during a European tour the year before. Jones contributed the swinging “Bumpkins” to this set, with Wallington penning the rest, save the traditional “Frankie and Johnnie” and “Summertime”, a Gershwin standard that gets a reading in the lineage of the “cool” here. “Baby Grand” and “Festival”, the album’s most upbeat tunes, feature standout solos by tenor saxophonist Frank Foster, who cuts through the mix with pinpoint accuracy. Slowing things way down at the end of side 1, “Christina” is a quiet, sweet ballad named after the three year-old daughter of jazz publicist Virginia Wicks.

|

| Quincy Jones |

The album has proved a delightful listen start to finish and has resonated with me on many levels. It tastefully tows the line between swing and bop throughout, making it a refreshing break from the hard bop sets that comprise most of my collection. There’s not a weak track on either side — I had a very difficult time narrowing my selections down to three. The band sounds incredibly tight and must have been well rehearsed before they stepped into the studio that day. I also appreciate the limitations of the ten-inch format as reflected in how succinct all the takes are. Surely a carryover from the 78 era and that format’s very short runtime of three-and-a-half minutes tops, in 1954 bands must have still been in the mentality of making every musical statement count with efficiency and precision, something that wouldn’t change until the twelve-inch LP format became the standard the following year. The shorter program length here works to the group’s advantage and it makes each listen that much more special.