- Original 1957 pressing

- “Six-eye” labels

- Deep groove on both sides

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Red Garland, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

All tracks recorded at Columbia 30th Street Studio, New York, NY

“Ah-Leu-Cha” recorded October 26, 1955

“Bye Bye Blackbird”, “Tadd’s Delight”, “Dear Old Stockholm” recorded June 5, 1956

“‘Round Midnight”, “All of You” recorded September 10, 1956

Originally released March 1957

| 1 | ‘Round Midnight | |

| 2 | Ah-Leu-Cha | |

| 3 | All Of You | |

| 4 | Bye Bye Blackbird | |

| 5 | Tadd’s Delight | |

| 6 | Dear Old Stockholm |

Selections:

“Ah-Leu-Cha” (Parker)

“Bye Bye Blackbird” (Dixon-Henderson)

For Collectors

Technically the third copy of this I’ve owned, my first copy was acquired on eBay, overpriced, and in rough shape. The second wasn’t much better, but this copy, acquired at the WFMU Record Fair in New York City a few years ago for a very reasonable price, is in fantastic condition, as you will hear!

Original pressing all around — I don’t personally get caught up in the matrix code game. For labels like Columbia, a matrix code can be used to identify the stamper and other metal parts used to press a particular copy of an album. The idea is that the quality of these parts deteriorates to some degree as each part is used in the manufacturing process, and thus that copies fashioning lower part numbers in the inner run-out section of each side have the potential to sound better (for more info on the vinyl manufacturing process, check out Deep Groove Mono’s links page).

From the information I’ve gathered, however, this difference will typically be so minuscule that it would be difficult to hear the difference between two records made from different parts (provided both copies were sourced from the same master lacquer disk). This is why I’ve chosen to stay away from the matrix code melee. In any event, for all you stamper geeks out there, this particular copy of Miles Davis’ classic ‘Round About Midnight was made from a “1C” stamper for side 1 and a “1A” stamper for side 2.

For Music Lovers

“The First Great Miles Davis Quintet” would have begun formulating around spring 1955 when pianist Red Garland and drummer Philly Joe Jones first joined the trumpeter for a recording session at Van Gelder Studio in Hackensack, New Jersey (The Musings of Miles, Prestige 7014). A few months later, bassist Paul Chambers and the harmonically curious yet ever-precise tenor saxophonist John Coltrane would complete the combo.

In addition to leading his new band, Miles was simultaneously eager to make the move from Prestige to Columbia Records. But the rising star still owed Prestige label head Bob Weinstock four more albums under contract. So before Columbia could release any material under the Davis moniker, Miles would need to fulfill his agreement with Weinstock. What then commenced in 1956 for the newborn quintet was a mash-up of Prestige and Columbia dates, all of which have since been heralded as classics.

‘Round About Midnight, Davis’ Columbia Records debut, was recorded in three sessions between October 1955 and September 1956 at Columbia’s historic 30th Street Studio in New York City. Many of you will already be familiar with the legendary sound of this studio. I find the sound on this particular album to be more immediate and up-front than the roomier sound heard on later Miles albums recorded here (Kind of Blue, for example). Nonetheless, the cathedral-turned-studio’s sonic blueprint is committed to tape here and the results are simply gorgeous.

|

| Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio |

Davis’ inaugural Columbia release is a highly consistent effort. On the album’s second tune, Miles takes Charlie Parker’s “Ah-Leu-Cha” at a faster tempo than the composer did on his own leisurely-paced 1948 recording (yet nowhere near as fast as Davis did at Newport in 1958), and though the leader opts for the bolder sound of an open horn here and on “Tadd’s Delight”, Davis’ signature muted trumpet sound dominates the album and is ultimately immortalized on ‘Round About Midnight. (It’s a shame that the quintet’s version of “Sweet Sue, Just You” didn’t make it to the original album release — a stellar take that could have only been left off as a practical matter of space — though fortunately it does appear on the 2001 Sony Legacy CD reissue.)

No sooner than alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley joined the group in early 1958 did Red Garland leave, unable to tolerate the leader’s sky-high standards. Jones would soon follow, and the First Great Quintet’s short reign would come to a close after the recording of Milestones. ‘Round About Midnight is thus one of the few examples of this iconic ensemble’s explosive power, and the album has stood the test of time as a rare combination of brilliance and accessibility equally fitting for attentive listening and unwinding.

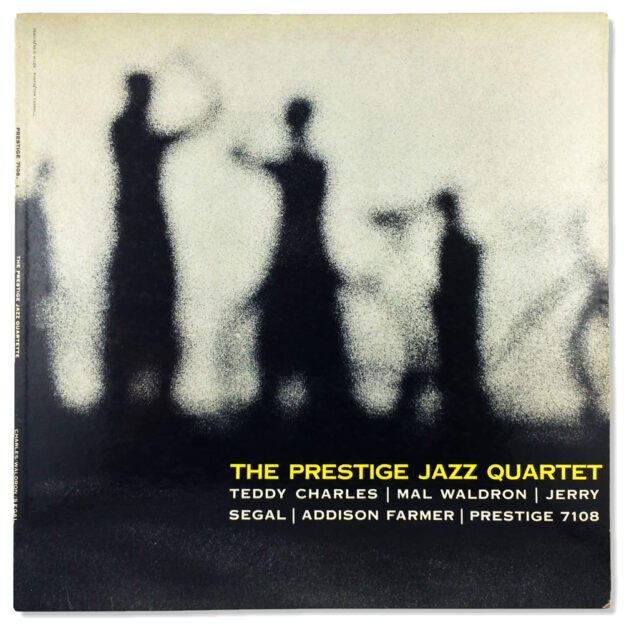

Vinyl Spotlight: The Prestige Jazz Quartet (Prestige 7108) Original Pressing

- Original 1957 pressing

- “446 W. 50th ST., N.Y.C.” on both labels

- Deep groove on both sides

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Teddy Charles, vibraphone

- Mal Waldron, piano

- Addison Farmer, bass

- Jerry Segal, drums

Recorded June 22 and June 28, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

| 1 | Take Three Parts Jazz | |

| 2 | Meta-Waltz | |

| 3 | Dear Elaine | |

| 4 | Friday the 13th |

Selection: “Dear Elaine” (Waldron)

For Collectors

Prestige released numerous LPs in the late ’50s, many of which stand today as interesting mixes of rarity, low demand, and musical excellence. This album is one example of that. I first heard it on Spotify and instantly took to it, but the master tape had noticeably degraded by the time of its digital mastering. So it became a priority of mine to seek out an original. One weekend afternoon last winter I was checking out a Swedish jazz dealer’s website and there it was, an original pressing touting VG++ condition. The asking price was a tad high so I talked the seller down a little and about ten days later the LP arrived at my doorstep. Quiet vinyl is a must for quiet music like this, and as you will be able to hear in the clips above, this one’s definitely a keeper.

I was instantly a fan of the album art as well, which portrays a serene scene of silhouettes that to me appear to be practicing tai chi. What connection the cover is intended to have with the music I do not know, though I do find that its grey, clouded imagery complements the mood of the music quite well.

For Music Lovers

A pair of forward-thinking composers, Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron first recorded together in January 1956 for Atlantic Records release 1229, The Teddy Charles Tentet. A year later they collaborated on five albums in just as many months, four of which were recorded for Bob Weinstock’s Prestige and New Jazz labels (Olio, Prestige 7084; Coolin’, New Jazz 8216; Teo, Prestige 7104). The last album in the run is presented here, captured on two dates in late June 1957.

The soft timbres of The Prestige Jazz Quartet convey a calming mood throughout, even during the more uptempo moments. The album has experimental leanings that weren’t yet trendy in 1957, but the sparse solos hardly beg for the listener’s attention. The quartet arrangement with vibraphone makes for a spacious atmosphere that lends itself well to the nuances of the vibes. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder has also set the drums further back in the mix than usual, making even more room for the dreamy echoes of the vibes to resonate.

The program begins with a trio of movements penned by Charles (“Take Three Parts Jazz”), followed by a pair of Waldron compositions (“Meta-Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”) and concluding with a lesser-known Thelonious Monk tune, “Friday the Thirteenth”. “Route 4”, the first third of Charles’ piece, is an ode to the highway traveled by hundreds of the Big Apple’s finest jazz musicians traveling to and from Van Gelder’s home studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. The piece’s other bookend, “Father George”, refers to another passageway between the city and Van Gelder’s, the George Washington Bridge. “Lyriste”, the title of the middle section, is an invented word of Charles’ crafting that joins ‘lyrical’ and ‘triste’. In accordance with the titles, perhaps Charles intended the piece to serve as a soundtrack for a somber commute back to the island after a long day of recording, where use of the word ‘triste’ might have been meant to suggest that trips to Van Gelder’s were for many of the musicians a welcome break from the routine of city life.

Accompanying Charles and Waldron are bassist Addison Farmer (twin brother of trumpeter Art Farmer) and drummer Jerry Segal. Segal avoids complicating things by playing with tasteful restraint throughout, and Farmer more than plays his part by delivering an impressive solo on “Meta-Waltz”. Side B begins with “Dear Elaine”, an apprehensive sprinkling of notes that seems to provide a window into the mind of a cautious courter. Closing the album, Waldron’s regular use of refrain on “Friday the Thirteenth” creates a comforting sense of familiarity that culminates in an inspired hammering of adjacent keys. (In the original 1953 recording of the tune, Monk is in his prime, rightly delivering an astonishing solo, though there’s something about hearing that melody played on the vibes that makes more sense to me than hearing it on Rollins’ sax…what do you think?)

Charles and Waldron would collaborate sporadically moving forward, but this would be the last time the entire ensemble would be in a recording studio together. Despite it being a short-lived, lesser-known experiment, the Prestige Jazz Quartet was a group of exceptional talent that deserves its rightful place in the storybook of modern jazz.

Epilogue

When I was preparing to take photos of the album jacket last week, I heard something jostling around inside, so I took a peek and to my surprise there was a small piece of paper inside with what appeared to be two interviews dated 1958 and typed in Swedish (the country the record came from upon my purchase). I then thought it would be cool to post a scan of the paper and maybe send out an S.O.S. for help translating it, then I thought of Google Translate and decided to do the translation myself, which I am presenting here.

The reviews would have originally been published in two Swedish magazines, Estrad (“Bandstand” in English) and OJ (“WOW”), and both were written by well-known Swedish jazz musicians: saxophonist/arranger Harry Arnold, whose resume included working with Quincy Jones, and pianist/composer Lars Werner. The original owner of the record must have been in the habit of typing up reviews for all the records they owned (perhaps to make up for the fact that they couldn’t read the English liner notes). Arnold seems the more opinionated of the two, possibly due to being more experienced and knowledgeable, though the way in which Werner has been charmed by the music resonates more with me. Through my amateur translation I also sense that Arnold’s review is surprisingly informal and that Werner was the better writer of the two (I also favored what I heard of Werner’s own music on YouTube).

For me, finding that piece of paper and reading the reviews felt like being transported back to the endlessly fascinating time that these records were made in, and I thought I’d share my experience with anyone who feels similarly nostalgic. I hope you enjoy!

Harry Arnold, Estrad (Bandstand), February 1958:

Harry Arnold

Of course I could try to make this into a pompous analysis of this record, but since it is said that honesty is best kept at a distance — all right, I do not have much profound to say about this record. Do not think that I condemn the whole thing because I absolutely do not; I’m just so damn precarious about it.

Perhaps the review will be more useful if I stick to the basics. The quartet consists of vibraphone, piano, bass, and drums, so it is tempting to draw parallels with the Modern Jazz Quartet. Here and there the style is similar, but the compositions are not in the “classical” spirit, as is usually the case with John Lewis and partners.

Side one is occupied by a work endowed “Take Three Parts Jazz”. It is a symphony in three movements with names “Route 4”, “Lyriste”, and “Father George”. In addition there is a song called “Meta-Waltz” on the same side.

On “Friday the Thirteenth”, which Thelonious Monk wrote, I think the whole thing suddenly begins to sound more natural, this may possibly be due to the fact that Monk has a truer sense of jazz when he composes than the other composers on the disc have?

I think pianist Mal Waldron stumbles too much at times, and the slow vibrato on the vibraphone affects my nerves in an unpleasant way. I think that the chord changes become one soporific grinding — but I appreciate the disc in a way, because I have a feeling Teddy Charles and the others have a bona fide interest in reinventing jazz without resorting to hysterical effects. It should also be noted that the solos are quite interesting at times.

Lars Werner, OJ (WOW), January 1958:

Lars Werner

In both name and composition, listeners will inevitably be tempted to compare this group with the Modern Jazz Quartet, which of course for a long time almost had a monopoly on sales in the vibraphone quartet market. However, the Prestige group’s music is of an entirely different character than MJQ’s: it is less stylized and lacks a certain coolness while spanning over a larger emotional register. There is certainly no equivalent in the Prestige Jazz Quartet to the personality that is John Lewis in MJQ, nor a soloist by Lewis’ standards, but Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron’s music proves capable of keeping the listener’s interest alive naturally, and the brilliant bassist Addison Farmer gives an intense and unfailing swing to everything.

To their credit, Charles and Waldron have been doing a lot of experimenting that sometimes has more in common with contemporary musical manifestations other than jazz. Here however, it seems that they have started from the rich ballad tradition found in jazz, and I feel they have found success with this approach.

Charles’ contribution, the tripartite “Take Three Parts Jazz”, contains much more tangible musical material than some of the earlier stuff he has done. The piece is highly successful, with tempo changes, solos, and themes emerging out of necessity, and the sense of a greater whole is never lacking.

Waldron’s two contributions, “Meta Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”, display an unconventional touch and much melodic finesse. Both works are well prepared, and fortunately they lack the sort of searching character that has so easily crept into many attempts to break jazz conventions.

Finally, Thelonious Monk’s four-beat composition “Friday the Thirteenth” provides an opportunity for longer solos from Charles, Waldron, and Farmer.

As a soloist, Charles is not as virtuosic as Milt Jackson — who is the only one he has to compare. Charles plays fewer notes but often gets an aphoristic clarity of melody, which makes him a musician I like to listen to.

Waldron seems to look for things other than melodic development as a soloist. He is more interested in piano percussion characteristics, and piano solos become more of a series of rhythmic figures, albeit rather monotonous at times.

The Prestige Jazz Quartet is still only a gramophone ensemble, and I am afraid that its music lacks the accessibility of MJQ. But this album should in the long run be of greater importance than, for example, MJQ’s last album, which gets a little stale after a while.

Vinyl Spotlight: Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims (Blue Note 1530) UA Mono Pressing

- United Artists mono reissue circa 1972-1975

- “A DIVISION OF UNITED ARTISTS RECORDS, INC.” on both labels

Personnel:

- Jerry Lloyd, trumpet

- Zoot Sims, tenor saxophone

- Jutta Hipp, piano

- Ahmed Abdul-Malik, bass

- Ed Thigpen, drums

Recorded July 28, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released February 1957

| 1 | Just Blues | |

| 2 | Violets for Your Furs | |

| 3 | Down Home | |

| 4 | Almost Like Being in Love | |

| 5 | Wee-Dot | |

| 6 | Too Close for Comfort |

Selections:

“Just Blues” (Sims)

For Collectors

This LP didn’t pique my interest until I saw an original pressing on the wall at an esteemed Manhattan record shop last fall. Though I was unfamiliar with the music, I knew of the record’s ‘holy grail’ status. Needless to say, I was intrigued. At this point in my time collecting I felt confident handling such an expensive piece, and when I removed the vinyl from the sleeve it was beautiful — Lexington Ave. labels, flat edge, deep groove, all the trimmings. When I got home later that evening I gave it a listen on Spotify and quickly realized how fun and animated the music was. Though I had never spent anywhere near the asking price on a record before, the thought that I may never see the record again eventually captivated my mind, so I arranged an in-store audition.

I set out with cash in hand, ready to make what I believed to be a respectable offer. When I got to the store, I took a more careful look at the record before it played. Visually it was beautiful with only some light scuffing. When side 1 began, the music sounded loud and present and I liked what I heard. The second song, the ballad “Violets for Your Furs”, was quieter though, and revealed light yet consistent surface noise. The owner said the record had been cleaned, which was a bit disconcerting in consideration of the noise I was hearing. I began listening more carefully, and by the time the needle got to trumpeter Jerry Lloyd’s solo on “Down Home”, the last song on the first side, the deal was dead, as inner groove distortion was evident. I thanked the owner for his time and left the shop a (much) wealthier person.

At this point I knew I loved the music, so I picked up the Classic Records reissue. It sounded great, but I still wanted to see if there was something I was missing out on that could only be provided by a younger, fresher master tape. So I sought out the copy you see here, an early ‘70s United Artists copy (technically the second ever pressing of the album). Ultimately, the master tape sounded similar with both pressings and I decided to keep the UA.

(Note: The following two paragraphs were updated June 2024.) At this point it is clear that at least some of these UA mono LPs were exported for sale in Japan, as many copies can still be found with Japanese “OBI” stickers. The common cut corners with these records signal either promotional use or discounted/no-returns status. Additionally, although these early ’70s Blue Note reissues are some of the earliest to not be mastered by Rudy Van Gelder, Liberty Records had begun using other mastering engineers as early as 1966. But who mastered many of these United Artists reissues remains a mystery.

Some of these US reissues are not sourced from the original tapes. According to Blue Note archivist Michael Cuscuna, United Artists would have been the first parent label to demand that Blue Note’s original master tapes be duplicated (sometimes with Dolby noise reduction) in the event that the tape was beginning to flake. (This is why original copies of classic Blue Note albums with Van Gelder mastering are so valuable: there is no debating that they were made using first generation tapes shortly after the recording sessions.) But this myriad of possibilities doesn’t seem to have much of an effect on the quality of this particular finished product, the results of which can be heard in the needledrops above.

For Music Lovers

To stand out in the testosterone-overrun world of instrumental jazz, it certainly didn’t hurt that German-born pianist Jutta (pronounced “Yoo-ta”) Hipp was a woman. That’s probably what esteemed jazz critic Leonard Feather was thinking in 1954 when he began nurturing the undiscovered talent. After hearing a friend’s recording of her, Feather booked studio time in Germany for the 29-year-old redheaded bopper (New Faces – New Sounds from Germany, Blue Note 5056), then arranged for Hipp to come to New York City in November 1955 for a residency at the Hickory House on East 52nd Street. The six-month stretch that followed proved quite an eventful time for the pianist. She was recorded on location by Blue Note in April (Jutta Hipp at the Hickory House, BLP 1515/6), and amongst the plethora of world-renowned jazz musicians whose acquaintance she had the pleasure of making, Hipp was reunited with tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims, whom she had originally jammed with on the Continent a few years back when Sims was on tour with bandleader Stan Kenton.

Hipp woud eventually be asked to assemble a combo for a Blue Note session at the label’s holy house of sound, engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s home recording studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. Sims would be recruited along with drummer Ed Thigpen, the backbone of Hipp’s Hickory House trio. Trumpeter Jerry Lloyd came along with Sims and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik entered the equation as well. Overseen by Alfred Lion, a fellow German native, the session commenced in late July 1956 and produced the entirety of the LP in a single day.

The band warmed up with a pair of ballads: the Matt Dennis-Tom Adair composition “Violets for Your Furs” (first recorded by Frank Sinatra two years prior), and the standard “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)”. The former took what was perhaps a nervous Hipp four takes to get through, and while the time constraints of the LP format wouldn’t allow the latter on to the original release, it would surface for the first time 40 years later along with George Gershwin’s “’S Wonderful” on the 1996 Connoisseur Series compact disc.

|

| Sims and Hipp rehearsing at Van Gelder Studio |

Hours later, by the time seven songs were laid to tape, the session was all but complete when Sims would have suggested the band riff on an up-tempo twelve-bar progression of his choosing. The result was “Just Blues”, and the track proved to be so much fun that it would later be chosen as the album’s opener. (In a review for All About Jazz, critic Chris M. Slawecki quipped, “Sims contributed the opening “Just Blues”, although he apparently couldn’t be bothered to title it,” which provokes the comical image of Lion turning to Sims for the title after the take with Sims shrugging and humbly replying, “Just blues.”)

The album would eventually make it to store shelves seven months later in February 1957. But by this time Hipp had mysteriously disappeared from the scene, and without star power to drive album sales, the sides wouldn’t be repressed until the glory days of hard bop were long over, rendering the original LP a figment to the vast majority of the jazz record collecting populous.

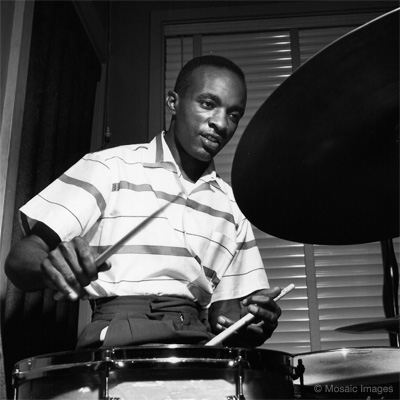

On first listen, the music here may sound a bit old-fashioned when held up to other cutting edge jazz albums recorded in 1956, but the consistently fun vibe of Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims proves difficult to deny. Sims would assume the unofficial role of leader that day, bringing a playful, infectious energy to the studio, and Hipp rose to the occasion despite known confidence issues. Thigpen, who would go on to form one-third of the legendary Oscar Peterson Trio, provides a steady, driving rhythm throughout, putting the soloists in the zone with inspiring momentum on more upbeat tunes like “Just Blues”, Lloyd’s “Down Home” and the J.J. Johnson composition “Wee Dot”.

|

| Drummer Ed Thigpen |

The recording itself is one of Rudy Van Gelder’s finest. By 1956 the engineer had finally backed off the quirky artificial spring reverb that hinders many of his earliest recordings, allowing listeners to hear the natural ambience of the Hackensack living room in all its makeshift glory. Soft, warm cymbals also define Van Gelder’s sound during this period, giving the music a unique, almost cartoony character. For the finishing touch, Reid Miles provided some of his most iconic design: a colorful, modern jumble of rectangles primitively imitating the keys of a piano (the cover has proven so iconic it has found a home in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City).

Sadly, this was the last time Hipp would enter a recording studio. At some point the pianist became jaded by the music industry, retreating to Queens to work in a textile factory. She returned to her first creative passion, painting, and lived alone there until 2003 when she passed away due to terminal illness. There are only a few recordings of the German phenom to be heard as a result, and we should be grateful for this particular shining example of her talents.

Vinyl Spotlight: John Coltrane, Giant Steps (Atlantic 1311) Mono vs. Stereo Edition

- Fifth mono pressing circa 1966

- Orange & purple label

- Box logo side 1; black fan logo side 2

- Side 1/2 matrix: 11637-A “AT” / 11638-A “AT”

VERSUS!

- Second stereo pressing circa 1960-1962

- Green & blue label

- Deep groove on both sides

- White fan logo on both sides

- Side 1/2 matrix: AVCO ST-A-59201 / AVCO ST-A-59202

Personnel:

All but “Naima”:

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Tommy Flanagan, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Art Taylor, drums

“Naima” only:

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Wynton Kelly, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Jimmy Cobb, drums

All but “Naima” recorded May 4-5, 1959; “Naima” recorded December 2, 1959

All selections recorded at Atlantic Records’ 56th Street studio, NYC

Originally released January 1960

| 1 | Giant Steps | |

| 2 | Cousin Mary | |

| 3 | Countdown | |

| 4 | Spiral | |

| 5 | Syeeda’s Song Flute | |

| 6 | Naima | |

| 7 | Mr. P.C. |

Selections:

“Giant Steps” (Coltrane) [Mono]

“Giant Steps” (Coltrane) [Stereo]

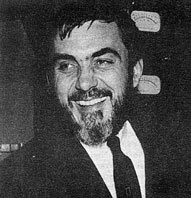

Tom Dowd

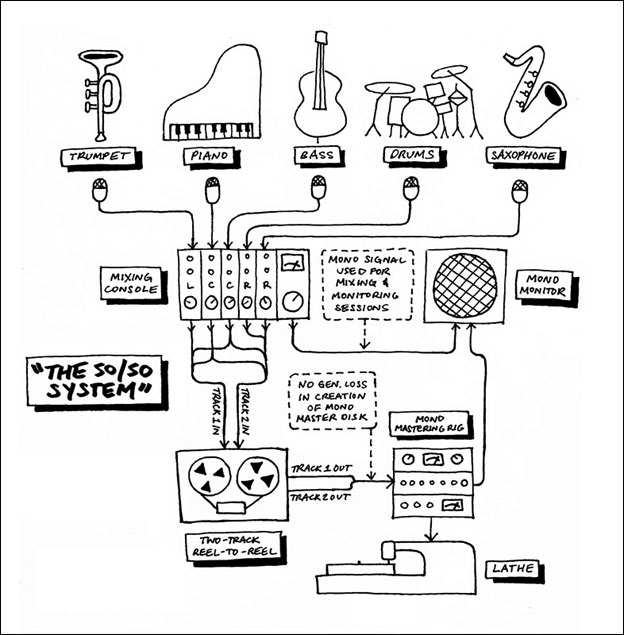

Giant Steps was recorded at Atlantic’s infamous 56th Street “office studio” under the supervision of legendary recording engineer Tom Dowd. According to the album’s liner notes, it was recorded to an Ampex 300-8R eight-track tape recorder, the results of which are two distinct i.e. ‘dedicated’ mixes, meaning the mono mix is not a ‘fold-down’.

The mono: Coltrane is front and center in this dark, bass-y mix. Trane and pianist Tommy Flanagan sit in good relationship to each other, though Paul Chambers’ bass doesn’t have a whole lot of definition, and Art Taylor’s drums get a bit buried behind Coltrane’s screaming presence.

The stereo: No instruments are presented center here, which for better or worse takes something away from Trane’s presence. (I doubt that Dowd was not yet privy to the theory of the ‘phantom center image’, and I can’t help but wonder why he was still not utilizing the center at this time.) Chambers’ bass still lacks good definition, though the spread gives Taylor more room to cut through. My first version of this album was the original 1990 stereo CD and I always appreciated how well I could hear the nuances in Taylor’s drumming in the stereo mix (I especially love the detail of the ride cymbal).

Head-to-head: On speakers, both mixes sound quite full, but in headphones the stereo version’s wide spread and its emphasis on the bass and treble leaves the mono feeling quite thin. However, Coltrane commands more presence in the mono mix, not only because he has been shifted from the far left to the center, but the mono also seems to favor the midrange, where the saxophone’s timbre is largely defined. This is probably why I feel that Coltrane sounds a bit muffled in the stereo mix when compared to the mono.

The verdict: Through speakers, both mixes sound great to me and I’d be happy to own either copy if I didn’t have a choice. But while I can only assume that most die-hard Coltrane fans will prefer the leader’s stronger presence in the mono mix, I personally love hearing all the nuances of Taylor’s kit in the stereo mix through headphones, which is probably why this is my favorite listening experience overall.

To play us out, I have included “Naima” as an added bonus because it is simply one of my favorite ballads of all-time. I chose the mono version because I find that the tune’s sparse composition works better without all the ‘empty space’ inherent in the stereo mix.

“Naima” (Mono)

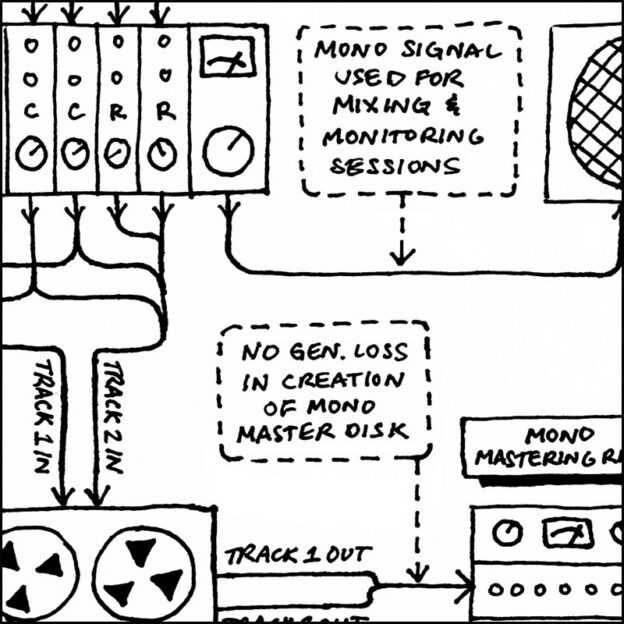

How They Heard It: Blue Note Records and the Transition from Mono to Stereo

Several years ago, when I first became a collector of vintage jazz records, I was confused. Original mono copies of albums from Blue Note’s classic catalog were significantly more expensive than their stereo counterparts, yet virtually all the talk online was of the original “stereo” master tapes for these sessions. Why then were the mono copies so much more valuable than the stereo copies if the albums were recorded to two-track tape?

I set out to find the answer, and soon discovered that there was a good amount of misunderstanding amongst audiophiles and record collectors regarding the methods of Blue Note’s exclusive recording and mastering engineer, Rudy Van Gelder. Realizing how historically and culturally important these recordings are, I decided to make a more formal study of the issue, and the results were published on the London Jazz Collector website in July of this year.

Shortly after publishing, I decided that the article could be made much more efficient, and last month London Jazz Collector published the revised version of the article. The new version is more concise and hopefully easier to understand. Click on the link below to check it out!

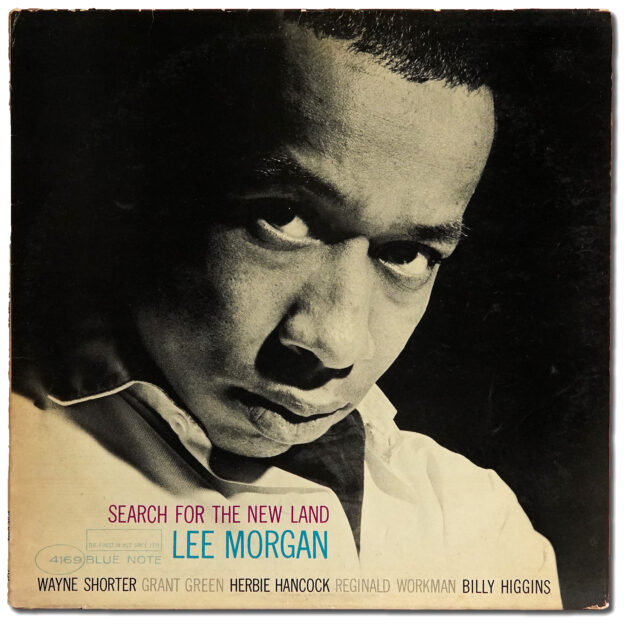

Vinyl Spotlight: Lee Morgan, Search for the New Land (Blue Note 4169) “Earless NY” Mono Pressing

- Second mono pressing circa 1966

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket

Personnel:

- Lee Morgan, trumpet

- Wayne Shorter, tenor saxophone

- Grant Green, guitar

- Herbie Hancock, piano

- Reggie Workman, bass

- Billy Higgins, drums

Recorded February 15, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released in 1966

| 1 | Search for the New Land | |

| 2 | The Joker | |

| 3 | Mr. Kenyatta | |

| 4 | Melancholee | |

| 5 | Morgan the Pirate |

Selection:

“Melancholee” (Morgan)

For Collectors

This record is especially hard to find with the Plastylite “P”, though it does exist. I have had good experiences with Liberty pressings though, so I’m not hung up on finding an original pressing of this album. The first copy I had, also a Liberty pressing, was cheap but it had a few loud pops and clicks, which prompted me to seek out this replacement, which I think was fairly graded VG+.

For Music Lovers

It’s difficult to discuss a Lee Morgan album without considering where and how it fits into the dramatic and tragic story of his life. At the age of 20, Morgan first recorded as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in October 1958 for the classic album Moanin’. His residency with Blakey would continue until the summer of 1961 when Morgan and fellow Philadelphian Bobby Timmons made the decision to retreat to their hometown for relief from the heroin-infested New York jazz scene. Morgan would only step in the studio once over the course of the next two years for producer Orrin Keepnews (Take Twelve, Jazzland 980), but would eventually make his official return to the New York recording scene in the fall of 1963 for a date with Hank Mobley (No Room for Squares, Blue Note 4149). After taking an uncharacteristic date with the progressive Grachan Moncur III the following month (Evolution, Blue Note 4153), Morgan recorded The Sidewinder in December 1963. The smash hit wouldn’t be released until the following summer, however. In the meantime, Morgan entered the studio again in February 1964 to record Search for the New Land, which would ultimately be shelved until 1966 – perhaps as a result of the tremendous commercial success of Sidewinder.

While Morgan and Shorter had been bandmates in The Jazz Messengers for years before Morgan’s hiatus, this would be the first of only a handful of occasions where the trumpeter would record with Herbie Hancock. (I was surprised to learn that this was only the second time that Shorter and Hancock had recorded together.) Billy Higgins returned from the Sidewinder date – which would prove to be the start of a lengthy partnership between he and Morgan – while Grant Green and Reggie Workman rounded out the sextet.

For all the Blue Note sessions Lee Morgan had led since he began recording for the label in 1956, this would only be the second where the entire program was penned by Morgan himself (The Sidewinder being the first). As such, Search for the New Land is a beautiful contemplation of the then looming and uncertain future of jazz. It is not a desperate exodus out of bop; it can be better likened to a child on the ocean’s shoreline standing knee-deep in the waves, hesitant to submerge themself in the water. Search thus pushes the boundaries of hard bop just enough to keep within the sub-genres inherent structure.

The album is consistent and cohesive. The dreamy, somber choruses of the title track are flanked by improvisational sections fashioning a minimal harmonic structure that compliments the modal leanings of Hancock and Shorter (this session would predict their uniting with Miles Davis as members of his “second great quintet” later that year). Hancock especially shines on the take with a crisp solo exemplifying his clear and acute thinking at the piano. “Mr. Kenyatta” bounces between moods in much the same way as the title track, swaying back and forth between feelings of angst and playfulness. And while The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings refers to the closing pair of songs as “more than makeweights” but “more off-the-peg” in comparison to the rest of the material, this ironically is my favorite sequence of the album. “Melancholee” is a gorgeously despondent composition that gives us a hard, honest look at the inner workings of Morgan, and the uplifting melody of “Morgan the Pirate” follows closely behind to conclude the album with an air of optimism.

One can’t help but wonder if the aforementioned session with Moncur had a profound impact on Morgan. Perhaps his experimentation at this time was actually a rebellion against the avant-garde manifesto, an attempt to push the boundaries of the institution of bop without succumbing to the full-blown chaos of free jazz. Either way, Search for the New Land is an expressive journey to the edges of an idiom, and it stands as an important work created at a pivotal crossroad in the evolution of the jazz art form.

Vinyl Spotlight: Blue Mitchell, The Thing to Do (Blue Note 4178) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1965 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket

Personnel:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet

- Junior Cook, tenor sax

- Chick Corea, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- Al Foster, drums

Recorded July 30, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released May 1965

Selection: “Step Lightly” (Henderson)

For Collectors

If you’ve read my first “Perspective” article here on Deep Groove Mono, you already know the story of how I acquired this record, which is special to me because it was the first vintage Blue Note album I ever heard that truly embodied the legendary “Blue Note sound”. And how about that cover? The symmetry, the cool blue on the dead black background, and the detailed shot of Blue’s hands on his trumpet make for a winning combination in my book.

For Music Lovers

I’m a huge Horace Silver fan, and I have always enjoyed the work of Blue Mitchell and tenor saxophonist Junior Cook as members of the Horace Silver Quintet. Mitchell had been working with Silver for four solid years the first time he entered the studio as a leader for Blue Note in August 1963 for a session including Joe Henderson and Herbie Hancock (for some reason, the recordings were shelved for nearly two decades). Two months later in the fall of ’63 though, Blue, Junior, and Quintet bassist Gene Taylor would have their last hurrah recording with Silver on a date producing two takes which would eventually find their way to Song for My Father. I haven’t read anything regarding the musicians’ parting of ways, but one can only guess it was peaceful, especially in light of the fact that Blue had jammed with Henderson, Cook’s replacement, before Silver.

Nine months later in the summer of 1964, Blue, 34 at the time, got Cook and Taylor together with a couple bright and budding musicians who would go on later to obtain global exposure with Miles Davis. 23-year-old Chick Corea had only recorded a handful of times when he arrived at Englewood Cliffs that day, and the 21-year-old Al Foster had yet to even set foot in a recording studio. But the pair rose to the challenge of this big-league outing with grace and poise, and their youthful energy ultimately steal the show on The Thing to Do.

If you think the head of the album opener, “Fungii Mama”, sounds zany or perhaps even corny, don’t let it deter you so quickly. Cook leads off with an inspiring solo, and Blue provides a fun improvisation of his own songwriting work. Corea eventually delivers a solo that is both fun and ambitious, and Foster follows with a challenging juxtaposition of the downbeat that causes the head to make a startling and exciting return. It’s a real treat to hear the young drummer’s rock-solid, driving latin rhythm throughout, and the tension created by each return to the bridge is a most welcome harmonic excursion.

My personal pick though is “Step Lightly”. The song was first recorded on the aforementioned 1963 date with Henderson and Hancock, but the overall vibe remains the same here. This track never really stood out to me until I recently heard it on a cloudy weekday afternoon off from work. The lazy tempo and bluesy melody complemented the mood so perfectly I instantly felt like I understood Henderson’s intentions as the song’s composer.

Sonically, this album is an example of Rudy Van Gelder at his best. The recording giant got a very nice piano sound here, and the natural reverberation of the Englewood Cliffs studio sounds heavenly, especially during Foster’s solo on “Fungii”. For those who don’t know, I’m a drum guy, and as such I recommend paying close attention to how tight and well-tuned Foster’s tom-toms sound here. (That’s one thing I love about classic jazz: the drum kits were made with care, the drummers took their craft seriously enough to tune their kits regularly, and you can hear the difference!)

Overall, I think the songwriting on this album is solid (Jimmy Heath’s title track included), and it gives us a rare glimpse of the vigorous, hungry duo of Corea and Foster on a straight-ahead bop date preceding their respective moves into free jazz and fusion. I personally need to be in the right mood to enjoy a record like The Thing to Do with its don’t-take-yourself-too-seriously-type attitude. But when I’m in that mood, these sides are as good as any.

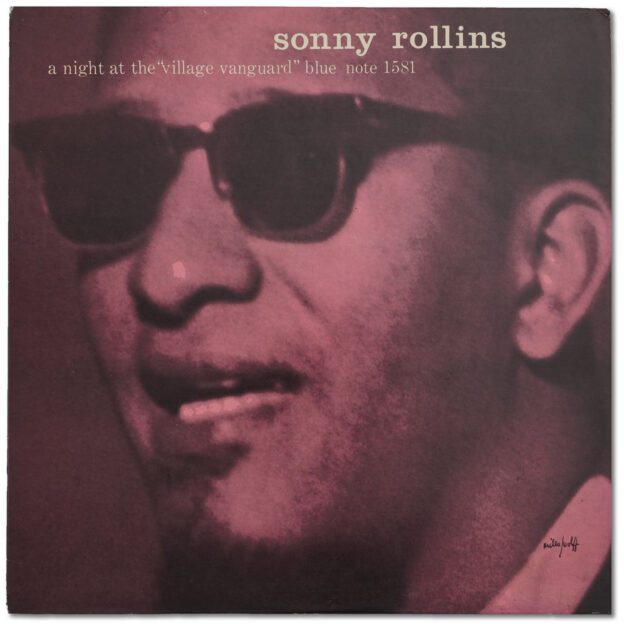

Vinyl Spotlight: Sonny Rollins, A Night at the Village Vanguard (Blue Note 1581) Liberty Mono Pressing

- Liberty pressing ca. 1966-70 (mono)

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

All but “A Night in Tunisia”:

- Sonny Rollins, tenor saxophone

- Wilbur Ware, bass

- Elvin Jones, drums

“A Night in Tunisia” only:

- Sonny Rollins, tenor saxophone

- Donald Bailey, bass

- Pete La Roca, drums

Recorded live at The Village Vanguard, New York City, November 3, 1957

Originally released December 1957

| 1 | Old Devil Moon | |

| 2 | Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise | |

| 3 | Striver’s Row | |

| 4 | Sonnymoon for Two | |

| 5 | A Night in Tunisia | |

| 6 | I Can’t Get Started |

Selection:

“Sonnymoon for Two” (Rollins)

Perhaps Monk and Trane are offering some insight into why an album like A Night at the Village Vanguard sounds so real and so raw. Rollins was a music rebel: I like to think of him as the most “punk rock” of all the bop greats (he even sported a mohawk over a decade before the inception of punk). He was also an insatiable innovator, so much that he went on a three-year hiatus from public and studio appearances because he was dissatisfied with his own progress as an artist. By 1957, it was apparent that Rollins felt confined to the underlying harmonic structure naturally imposed on him by piano accompaniment. His solution as a leader? Get rid of the piano player. Rollins recorded his first entire LP without keys in March of that year (Way Out West, Contemporary 3530), and on this November Vanguard date he decided to expand on the idea with two different rhythm duos during the afternoon and evening sets, respectively.

“Softly As in a Morning Sunrise” is a standout tune not only for the refreshingly humble solos from all three members of the evening trio (Rollins, Wilbur Ware, and Elvin Jones), but also for its sonic brilliance. I love how immediate and direct Rollins’ horn sounds (partly due to the lack of piano), and things are quiet enough during the bass and drum solos (audience included) for us to hear each and every nuance. I’ve always had a thing for drums, and Jones’ kit is astonishingly tight, tuned, and clear here — especially the bass drum. The only shortcoming is that the overhead miking of the drums tends to overload from time to time, resulting in the occasional distorted cymbal crash.

The complete survived takes from this session were first issued in 1999 on double-CD. Numbering triple the amount of songs here, this can be a daunting listen. I was first exposed to A Night at the Village Vanguard through the reissue, and as a record collector who has always approached music with a “less is more” mentality, I just focused on the original track listing anyway — which in all likelihood was carefully curated by Blue Note founder Alfred Lion. Someday I will probably get to a point where I feel familiar enough with this LP to move on to the rest of the reissue. But until then, I like that the record’s concise program naturally encourages me to focus more on the details of a smaller amount of material.