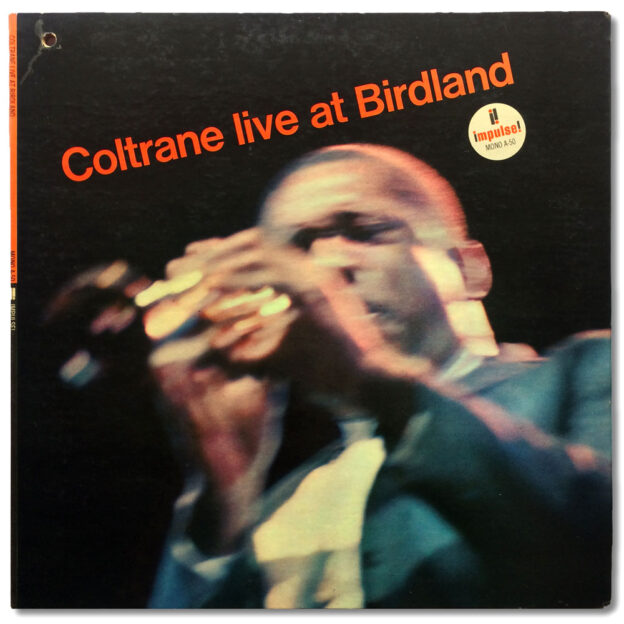

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “ABC-Paramount” on labels

- “VAN GELDER” in dead wax

Personnel:

- John Coltrane, tenor and soprano saxophone

- McCoy Tyner, piano

- Jimmy Garrison, bass

- Elvin Jones, drums

All but “Alabama”, “Your Lady” recorded October 8, 1963 at Birdland, New York, New York

“Alabama”, “Your Lady” recorded November 18, 1963 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Originally released April 1964

Selection: “Afro Blue” (Coltrane)

Generally speaking, I don’t know the Impulse catalog very well, and accordingly I have a harder time keeping track of the ‘first-first pressing’ melee associated with the label. Thus I’m not really sure if this is a ‘first-first pressing’ or just a ‘first pressing’, but it has the Van Gelder stamp of approval and, more importantly, it plays through without the hideous artifacts of groove wear so I’m a happy camper. This copy had a lot of light scuffs when I first looked at it, which is probably what kept the price down, but by the time I got it home and gave it a listen I was happy to find that this was a rare case of a record ‘playing better than it looked’. I am so inspired by the intensity with which John Coltrane played the soprano saxophone during this time period, and “Afro Blue” is a fine example of that passion and vigor.

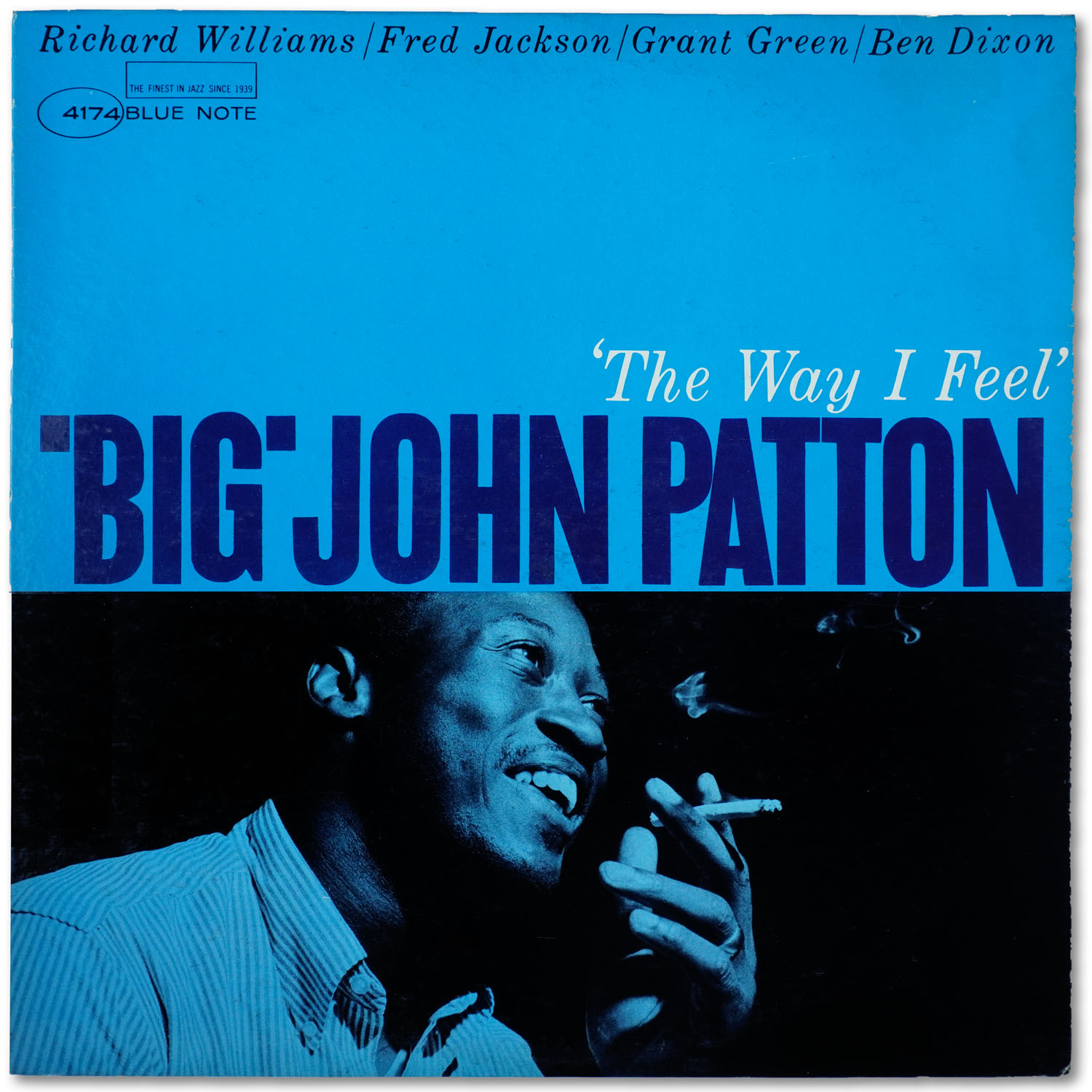

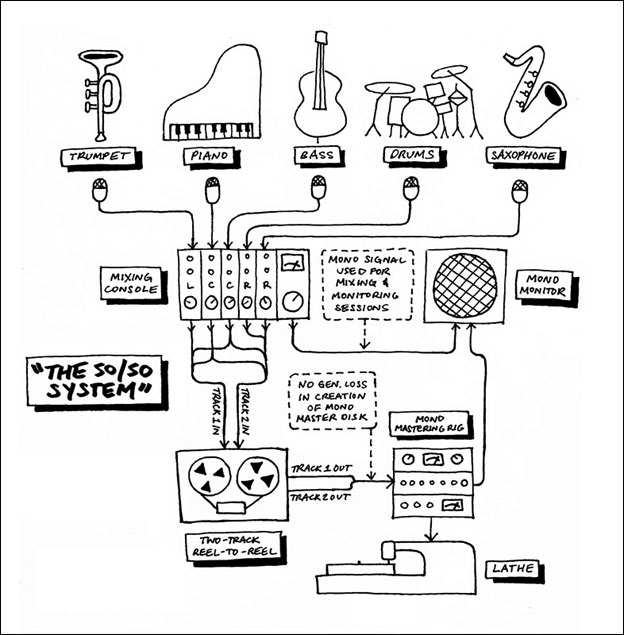

Vinyl Spotlight: Big John Patton, The Way I Feel (Blue Note 4174) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Richard Williams, trumpet

- Fred Jackson, tenor & baritone saxophones

- Grant Green, guitar

- John Patton, organ

- Ben Dixon, drums

Recorded June 19, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released October 1964

| 1 | The Rock | |

| 2 | The Way I Feel | |

| 3 | Jerry | |

| 4 | Davene | |

| 5 | Just 3/4 |

Selection:

“The Rock” (Patton)

A rare record in any format, this is the genuine article right here: Van Gelder stamp, Plastylite “P”, mono. After its original release in 1964, The Way I Feel was never reissued on LP or CD in the United States, and it has only been reissued twice in Japan on CD. The reason for the scarce number of reissues could be related to the fact that my Capitol Vaults digital copy has heavy audible tape damage in a couple of spots, which was a major reason I was so persistent in seeking out a vintage copy. However, I’ve owned a few copies of this over the years, all with original Van Gelder mastering, and I’m convinced that the mild distortion I hear on Richard Williams’ loudest trumpet blasts was baked into the original master lacquer disk and is therefore present on every copy. As much of an RVG fan-boy as I am, the truth is that the engineer was obsessed with obtaining a superior signal-to-noise ratio in his work and in the process mastered (and recorded) a little too hot at times.

This is one of my favorite Blue Note albums. It is definitely in my top five, partly because it is so consistent. When I first got into jazz, I followed a lot of ignorant stereotypes, one of them being that jazz with an organ isn’t “real jazz”. But John Patton looked so damn cool on this album cover that I had to give it a try, and it was undeniable how jazzy, soulful, and funky this record was all at once. John Patton’s music is lighthearted and occasionally funny, and the leader clearly succeeds at bringing those qualities out of his sidemen here (saxophonist Fred Jackson’s solo on “The Rock” is a good example). The title track’s laid-back groove breaks up the soulful tempo of the first side by strutting at the pace of a crawl, and though “Davene” sounded a bit hokey to me at first, I have since realized it to be a beautiful ballad that is now a favorite.

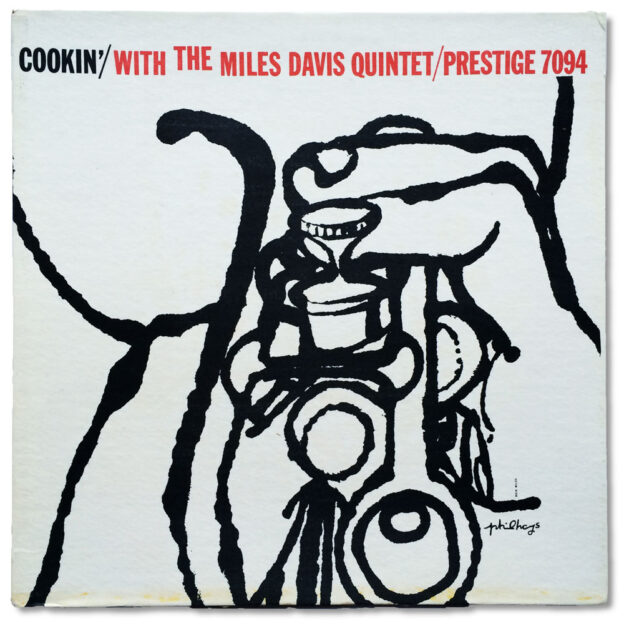

Vinyl Spotlight: Cookin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet (Prestige 7094) Second “Bergenfield” Pressing

- Second pressing circa 1958-1964 (mono) with small Abbey pressing ring

- “Bergenfield, N.J.” on both labels

- Deep groove on both sides

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Red Garland, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

Recorded October 26, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released in 1957

| 1 | My Funny Valentine | |

| 2 | Blues by Five | |

| 3 | Airegin | |

| 4 | Tune Up/When the Lights Are Low |

Selections:

“My Funny Valentine” (Rodgers)

“Tune Up” (Davis) / “When the Lights are Low” (Carter)

I found this record several years back at the first WFMU record fair I ever attended in New York City. It’s not an “original original” pressing in the sense that it lacks the “NYC” address on the labels, but it’s still made from original Van Gelder mastering. On the ballad “My Funny Valentine” especially, you should be able to hear that this is a very clean copy I was fortunate to find for the price I paid.

Much of what I might say about the history of this album I’ve already said in my review of Davis’ ‘Round About Midnight, which shares the same lineup. I originally bought this record mainly because it was a vintage copy in great shape and because I love this version of “My Funny Valentine”, but I eventually came to appreciate the entire second side of the album just as much (“Blues by Five” remains a ho-hum listen for me). Philly Joe Jones’ drum kit sounds thunderous here, and overall we get a glimpse of engineer Rudy Van Gelder in one of his finest hours at his Hackensack studio.

It would appear that this album and Relaxin’ (Prestige 7129) are the two most popular LPs of the four that Davis’ First Great Quintet recorded for Prestige, the others being Workin’ (Prestige 7166) and Steamin’ (Prestige 7200). I find something to like in all of them, but Cookin’, the first of the four to be released, is definitely my favorite. All four albums were recorded on just two dates in 1956. Renowned audiophile mastering engineer Steve Hoffman has claimed in his online forum that Van Gelder did a better job of recording the second date (which just so happened to produce all the takes present on Cookin’), claiming that Van Gelder made excessive use of spring reverb on the earlier of the two dates; I can’t say I agree. I think Cookin’ has the best program start to finish but I think all four albums are representative of how brilliant Van Gelder was under the restrictions of the mono format.

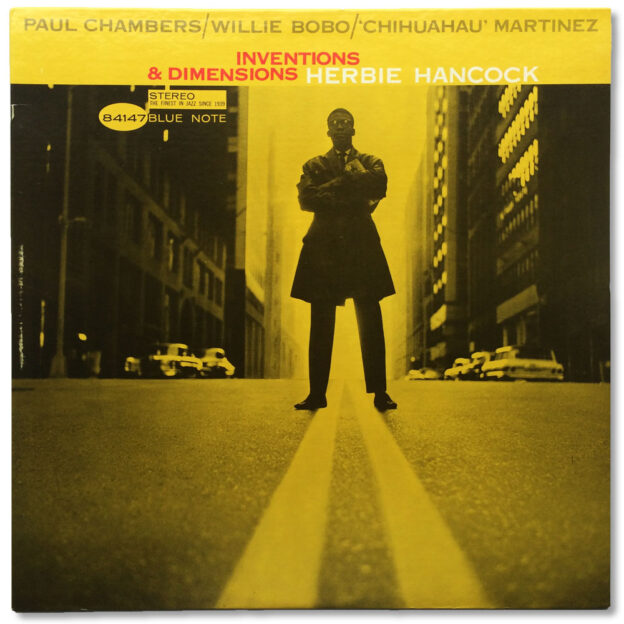

Vinyl Spotlight: Herbie Hancock, Inventions and Dimensions (Blue Note 84147) Liberty RVG Stereo Pressing

- Stereo Liberty reissue circa 1966-1970

- “A DIVISION OF LIBERTY RECORDS, INC.” on both labels

- “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Herbie Hancock, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Willie Bobo, drums and timbales

- Osvaldo “Chihuahua” Martinez, conga and bongo

Recorded August 30, 1963 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released February 1964

Selection:

“Triangle” (Hancock)

Although Liberty pressings of most classic Blue Note albums are not original pressings, they still have the potential to sound great. They may lack the Plastylite “P” found in the runout groove of most originals but they do usually brandish the Van Gelder stamp in the runout groove, indicating that they were made from the same master lacquer disk as an original. This stereo copy of Herbie Hancock’s third album for Blue Note may not be a first pressing but it still embodies engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s original mastering work.

Many collectors will shun any vintage Blue Note without the “P”, claiming that its absence takes something away from the listening experience. I beg to differ, having never heard a significant contrast between originals and subsequent Liberty-era pressings sourced from the original metal work. In fact, I have found that Liberty pressings are more likely to sound fresher since they are less likely than originals to have suffered excessive wear.

One does need to be careful of how far they venture away from the original release of an album, however. Van Gelder’s mastering was used well into the late ’70s after Liberty had sold Blue Note to United Artists, and depending on the title, it seems there is an increased chance that the original work parts will have lost some measure of quality by this time. These records are more likely to lack the ‘life’ of earlier pressings (usually a reference to lower distortion and better high-frequency detail).

Despite having heard the popular audiophile criticisms of Rudy Van Gelder’s mastering work, I often find his LP masters to be highly accurate, even, and dynamic. But be careful — you won’t get this experience if you’re listening to a worn record. This particular copy was purchased sealed a couple years back, which I feel makes it a shining example of the mastering engineer’s handiwork, certainly more so than any wear-ridden original.

As for the music, this is my favorite Herbie Hancock album. Every time I listen, I listen from start to finish. Hancock takes an experimental approach to the songwriting here and can often be heard working out ideas on the fly. This leads to frequent use of refrain, a technique that has never been popular with jazz soloists (because of the central role improvisation plays in the genre, jazz musicians often seem driven by an intense desire to constantly invent, which means never sitting on the same phrase for very long at all). My longstanding relationship with sampling and hip hop has made me very accustomed to repetition in instrumentation, which I think has much to do with why I find Hancock’s regular use of refrain here a very welcome break from the bop norm. Bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Willie Bobo intensify the trance-like qualities of the music by locking in on various rhythms throughout, and percussionist Chihuahua Martinez’s timing is rock solid — something crucial in a minimal arrangement like this.

Vinyl Spotlight: Kenny Dorham, Quiet Kenny (New Jazz 8225) OJC Stereo Reissue

- Original Jazz Classics stereo reissue circa 1986 (catalog no. OJC-250)

Personnel:

- Kenny Dorham, trumpet

- Tommy Flanagan, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Art Taylor, drums

Recorded November 13, 1959 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released February 1960

Selections:

“Lotus Blossom” (Dorham) [Stereo]

“Lotus Blossom” (Dorham) [Summed Mono]

For Collectors

After a couple years of collecting on a budget, the reality of the situation starts to sink in: you won’t be acquiring a first pressing of a holy grail like Kenny Dorham’s Quiet Kenny any time soon.

What makes an album a holy grail? Simply put, a combination of being very rare and very in demand. More specifically, in the case of this overlooked album, it probably has a lot to do with the fact that it didn’t get a proper second U.S. pressing until this version, the 1986 Original Jazz Classics reissue. (According to Discogs, Prestige released a Dorham album in 1970 simply titled 1959 with different album art but the same track listing as the OJC reissue, which includes the originally unreleased “Mack the Knife”.) To give the original even more allure, the tendency for reissue producers to have an overwhelmingly strong preference for stereo has rendered the original the only mono version of this album ever released.

There’s always something about reissues causing them to fall short of the excitement an original provides. Though I avoided Original Jazz Classics reissues for a while for this reason, I eventually relaxed my naïve original pressing snobbery and began considering reissues of favorites that were much too expensive in their first pressing form. I then read about how OJC reissues were by and large considered to be of exceptional sound quality, with the earliest of them guaranteed to be all analog as well (my copy had the original shrink wrap complete with the long rectangular OJC sticker characteristic of OJC albums released in the mid-80s). So I gave these reissues a chance, and by and large they have lived up to my expectations. The artwork and packaging are hit or miss with OJCs, though I think they did a good job with this release, and the fact that the labels mimic those used for the original New Jazz LP is an added bonus.

There’s always something about reissues causing them to fall short of the excitement an original provides. Though I avoided Original Jazz Classics reissues for a while for this reason, I eventually relaxed my naïve original pressing snobbery and began considering reissues of favorites that were much too expensive in their first pressing form. I then read about how OJC reissues were by and large considered to be of exceptional sound quality, with the earliest of them guaranteed to be all analog as well (my copy had the original shrink wrap complete with the long rectangular OJC sticker characteristic of OJC albums released in the mid-80s). So I gave these reissues a chance, and by and large they have lived up to my expectations. The artwork and packaging are hit or miss with OJCs, though I think they did a good job with this release, and the fact that the labels mimic those used for the original New Jazz LP is an added bonus.

For Music Lovers

Shortly after I got into jazz, I came across the OJC CD reissue of Quiet Kenny at a local library, and going off the album’s 3.5-star rating in The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings and its elite status among collectors, I decided to give it a try. Though the music didn’t immediately draw me in, I soon grew to appreciate the minimal arrangement and the big, empty, dark sound of Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. I also have a leaning toward more gentle styles of playing, which, as the title suggests, this album epitomizes.

|

| Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey |

Quiet Kenny features three Dorham originals: “Blue Friday”, “Blue Spring Shuffle”, and “Lotus Blossom” — not to be confused with “Lotus Flower”, another Dorham composition, a ballad that premiered in 1955 on the ten-inch Blue Note LP Afro-Cuban (BLP 5065). Though “Blue Friday” appears here for the first time, “Lotus Blossom” had first been recorded by Riverside in 1957 with a piano-less quartet led by Dorham (2 Horns, 2 Rhythm, Riverside 255). As much as I enjoy the less busy rendition presented here, the driving pace of the Riverside version along with the harmony offered by Ernie Henry’s sax make the Riverside version tough to beat. “Blue Spring Shuffle” had already been laid to tape as well, appearing several months prior with the truncated title “Blue Spring” on the LP of the same name (Blue Spring, Riverside 297). In this case I hold the more sparse arrangement here in higher regard.

The first track on Quiet Kenny that stood out to me was “Lotus Blossom”, the gentle, uptempo opener. Art Taylor’s solo shines here, the gorgeous sound of which is a combination of the drummer’s well-crafted, finely-tuned kit, Van Gelder’s EMT reverb plate, and the natural ambience of the engineer’s custom-built cathedral-like studio. “My Ideal”, the next song in the sequence, has become one of my favorite jazz ballads. The other ballad, “Alone Together” follows close behind, and overall I find Quiet Kenny to be a solid listen with a clean, sweet sound throughout.

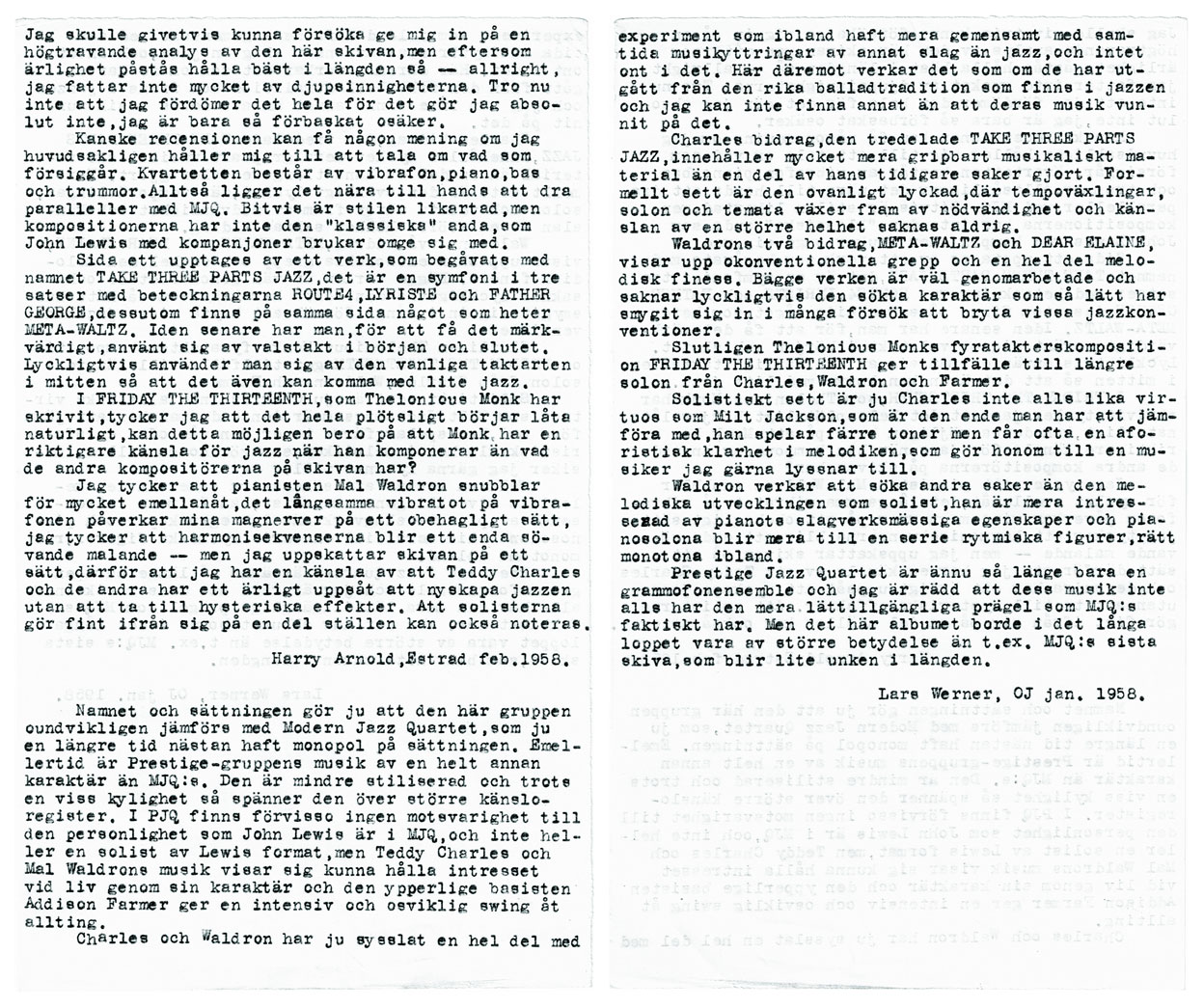

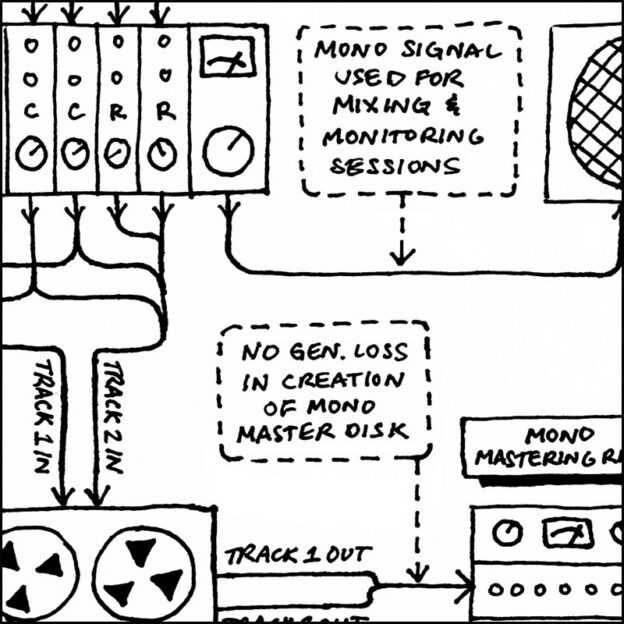

Mono vs. Stereo

Like many Blue Note albums released between the years of 1959 and 1962, every reissue of Quiet Kenny has been stereo despite the original release being exclusively mono. The best explanation for this would be that the album was recorded to two-track tape only. Since Van Gelder didn’t mix down to a separate master tape for mono releases in these instances (all mixing was done on the fly), reissue producers today would only be left with a two-track master tape to work with. And though it’s quite possible that these producers have unanimously preferred the stereo presentation to the mono, they may have also erroneously concluded that the album was monitored and mixed in stereo due to the absence of a mono master tape. But the fact that the inaugural release was strictly in mono strongly suggests the contrary. As a result, the only way to hear this music in mono today short of summing the channels of your stereo is to cough up $2,000+ USD for an original.

Offered here are both the stereo and mono presentations of the opening track for comparison (the mono obviously not being from an original pressing but the summing of the channels on my amplifier). Though the mono is cohesive where the stereo is somewhat disjoint and empty, I find the space created by the stereo spread too beautiful to collapse into a single channel.

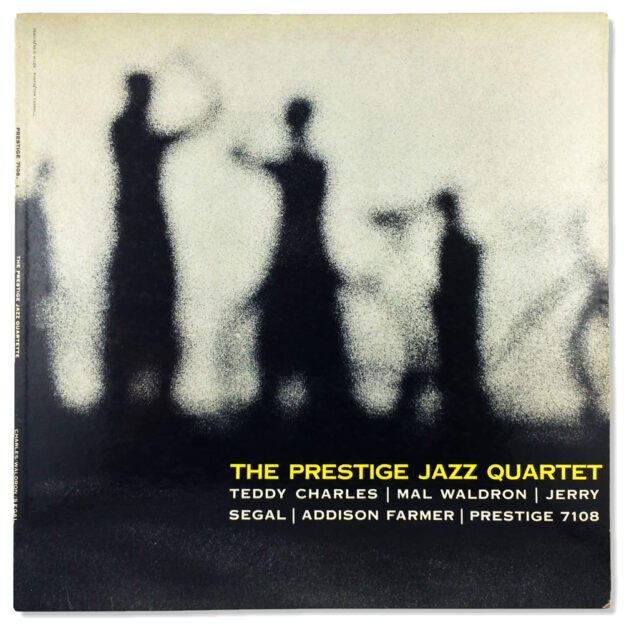

Vinyl Spotlight: The Prestige Jazz Quartet (Prestige 7108) Original Pressing

- Original 1957 pressing

- “446 W. 50th ST., N.Y.C.” on both labels

- Deep groove on both sides

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Teddy Charles, vibraphone

- Mal Waldron, piano

- Addison Farmer, bass

- Jerry Segal, drums

Recorded June 22 and June 28, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

| 1 | Take Three Parts Jazz | |

| 2 | Meta-Waltz | |

| 3 | Dear Elaine | |

| 4 | Friday the 13th |

Selection: “Dear Elaine” (Waldron)

For Collectors

Prestige released numerous LPs in the late ’50s, many of which stand today as interesting mixes of rarity, low demand, and musical excellence. This album is one example of that. I first heard it on Spotify and instantly took to it, but the master tape had noticeably degraded by the time of its digital mastering. So it became a priority of mine to seek out an original. One weekend afternoon last winter I was checking out a Swedish jazz dealer’s website and there it was, an original pressing touting VG++ condition. The asking price was a tad high so I talked the seller down a little and about ten days later the LP arrived at my doorstep. Quiet vinyl is a must for quiet music like this, and as you will be able to hear in the clips above, this one’s definitely a keeper.

I was instantly a fan of the album art as well, which portrays a serene scene of silhouettes that to me appear to be practicing tai chi. What connection the cover is intended to have with the music I do not know, though I do find that its grey, clouded imagery complements the mood of the music quite well.

For Music Lovers

A pair of forward-thinking composers, Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron first recorded together in January 1956 for Atlantic Records release 1229, The Teddy Charles Tentet. A year later they collaborated on five albums in just as many months, four of which were recorded for Bob Weinstock’s Prestige and New Jazz labels (Olio, Prestige 7084; Coolin’, New Jazz 8216; Teo, Prestige 7104). The last album in the run is presented here, captured on two dates in late June 1957.

The soft timbres of The Prestige Jazz Quartet convey a calming mood throughout, even during the more uptempo moments. The album has experimental leanings that weren’t yet trendy in 1957, but the sparse solos hardly beg for the listener’s attention. The quartet arrangement with vibraphone makes for a spacious atmosphere that lends itself well to the nuances of the vibes. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder has also set the drums further back in the mix than usual, making even more room for the dreamy echoes of the vibes to resonate.

The program begins with a trio of movements penned by Charles (“Take Three Parts Jazz”), followed by a pair of Waldron compositions (“Meta-Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”) and concluding with a lesser-known Thelonious Monk tune, “Friday the Thirteenth”. “Route 4”, the first third of Charles’ piece, is an ode to the highway traveled by hundreds of the Big Apple’s finest jazz musicians traveling to and from Van Gelder’s home studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. The piece’s other bookend, “Father George”, refers to another passageway between the city and Van Gelder’s, the George Washington Bridge. “Lyriste”, the title of the middle section, is an invented word of Charles’ crafting that joins ‘lyrical’ and ‘triste’. In accordance with the titles, perhaps Charles intended the piece to serve as a soundtrack for a somber commute back to the island after a long day of recording, where use of the word ‘triste’ might have been meant to suggest that trips to Van Gelder’s were for many of the musicians a welcome break from the routine of city life.

Accompanying Charles and Waldron are bassist Addison Farmer (twin brother of trumpeter Art Farmer) and drummer Jerry Segal. Segal avoids complicating things by playing with tasteful restraint throughout, and Farmer more than plays his part by delivering an impressive solo on “Meta-Waltz”. Side B begins with “Dear Elaine”, an apprehensive sprinkling of notes that seems to provide a window into the mind of a cautious courter. Closing the album, Waldron’s regular use of refrain on “Friday the Thirteenth” creates a comforting sense of familiarity that culminates in an inspired hammering of adjacent keys. (In the original 1953 recording of the tune, Monk is in his prime, rightly delivering an astonishing solo, though there’s something about hearing that melody played on the vibes that makes more sense to me than hearing it on Rollins’ sax…what do you think?)

Charles and Waldron would collaborate sporadically moving forward, but this would be the last time the entire ensemble would be in a recording studio together. Despite it being a short-lived, lesser-known experiment, the Prestige Jazz Quartet was a group of exceptional talent that deserves its rightful place in the storybook of modern jazz.

Epilogue

When I was preparing to take photos of the album jacket last week, I heard something jostling around inside, so I took a peek and to my surprise there was a small piece of paper inside with what appeared to be two interviews dated 1958 and typed in Swedish (the country the record came from upon my purchase). I then thought it would be cool to post a scan of the paper and maybe send out an S.O.S. for help translating it, then I thought of Google Translate and decided to do the translation myself, which I am presenting here.

The reviews would have originally been published in two Swedish magazines, Estrad (“Bandstand” in English) and OJ (“WOW”), and both were written by well-known Swedish jazz musicians: saxophonist/arranger Harry Arnold, whose resume included working with Quincy Jones, and pianist/composer Lars Werner. The original owner of the record must have been in the habit of typing up reviews for all the records they owned (perhaps to make up for the fact that they couldn’t read the English liner notes). Arnold seems the more opinionated of the two, possibly due to being more experienced and knowledgeable, though the way in which Werner has been charmed by the music resonates more with me. Through my amateur translation I also sense that Arnold’s review is surprisingly informal and that Werner was the better writer of the two (I also favored what I heard of Werner’s own music on YouTube).

For me, finding that piece of paper and reading the reviews felt like being transported back to the endlessly fascinating time that these records were made in, and I thought I’d share my experience with anyone who feels similarly nostalgic. I hope you enjoy!

Harry Arnold, Estrad (Bandstand), February 1958:

Harry Arnold

Of course I could try to make this into a pompous analysis of this record, but since it is said that honesty is best kept at a distance — all right, I do not have much profound to say about this record. Do not think that I condemn the whole thing because I absolutely do not; I’m just so damn precarious about it.

Perhaps the review will be more useful if I stick to the basics. The quartet consists of vibraphone, piano, bass, and drums, so it is tempting to draw parallels with the Modern Jazz Quartet. Here and there the style is similar, but the compositions are not in the “classical” spirit, as is usually the case with John Lewis and partners.

Side one is occupied by a work endowed “Take Three Parts Jazz”. It is a symphony in three movements with names “Route 4”, “Lyriste”, and “Father George”. In addition there is a song called “Meta-Waltz” on the same side.

On “Friday the Thirteenth”, which Thelonious Monk wrote, I think the whole thing suddenly begins to sound more natural, this may possibly be due to the fact that Monk has a truer sense of jazz when he composes than the other composers on the disc have?

I think pianist Mal Waldron stumbles too much at times, and the slow vibrato on the vibraphone affects my nerves in an unpleasant way. I think that the chord changes become one soporific grinding — but I appreciate the disc in a way, because I have a feeling Teddy Charles and the others have a bona fide interest in reinventing jazz without resorting to hysterical effects. It should also be noted that the solos are quite interesting at times.

Lars Werner, OJ (WOW), January 1958:

Lars Werner

In both name and composition, listeners will inevitably be tempted to compare this group with the Modern Jazz Quartet, which of course for a long time almost had a monopoly on sales in the vibraphone quartet market. However, the Prestige group’s music is of an entirely different character than MJQ’s: it is less stylized and lacks a certain coolness while spanning over a larger emotional register. There is certainly no equivalent in the Prestige Jazz Quartet to the personality that is John Lewis in MJQ, nor a soloist by Lewis’ standards, but Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron’s music proves capable of keeping the listener’s interest alive naturally, and the brilliant bassist Addison Farmer gives an intense and unfailing swing to everything.

To their credit, Charles and Waldron have been doing a lot of experimenting that sometimes has more in common with contemporary musical manifestations other than jazz. Here however, it seems that they have started from the rich ballad tradition found in jazz, and I feel they have found success with this approach.

Charles’ contribution, the tripartite “Take Three Parts Jazz”, contains much more tangible musical material than some of the earlier stuff he has done. The piece is highly successful, with tempo changes, solos, and themes emerging out of necessity, and the sense of a greater whole is never lacking.

Waldron’s two contributions, “Meta Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”, display an unconventional touch and much melodic finesse. Both works are well prepared, and fortunately they lack the sort of searching character that has so easily crept into many attempts to break jazz conventions.

Finally, Thelonious Monk’s four-beat composition “Friday the Thirteenth” provides an opportunity for longer solos from Charles, Waldron, and Farmer.

As a soloist, Charles is not as virtuosic as Milt Jackson — who is the only one he has to compare. Charles plays fewer notes but often gets an aphoristic clarity of melody, which makes him a musician I like to listen to.

Waldron seems to look for things other than melodic development as a soloist. He is more interested in piano percussion characteristics, and piano solos become more of a series of rhythmic figures, albeit rather monotonous at times.

The Prestige Jazz Quartet is still only a gramophone ensemble, and I am afraid that its music lacks the accessibility of MJQ. But this album should in the long run be of greater importance than, for example, MJQ’s last album, which gets a little stale after a while.

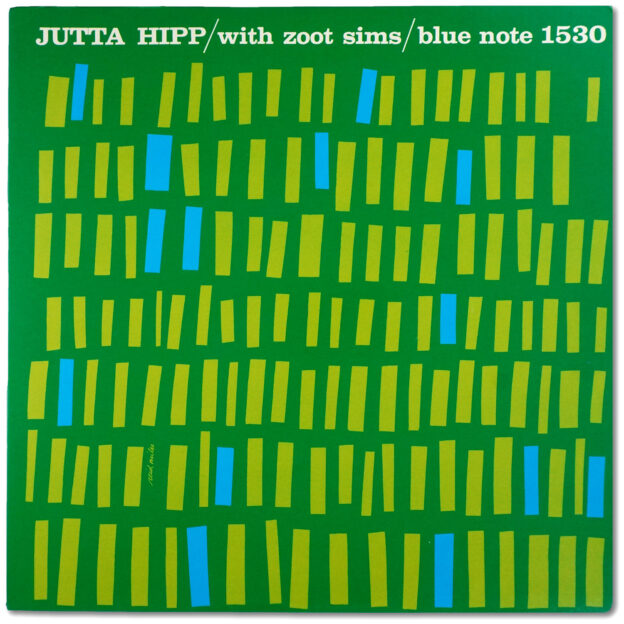

Vinyl Spotlight: Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims (Blue Note 1530) UA Mono Pressing

- United Artists mono reissue circa 1972-1975

- “A DIVISION OF UNITED ARTISTS RECORDS, INC.” on both labels

Personnel:

- Jerry Lloyd, trumpet

- Zoot Sims, tenor saxophone

- Jutta Hipp, piano

- Ahmed Abdul-Malik, bass

- Ed Thigpen, drums

Recorded July 28, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released February 1957

| 1 | Just Blues | |

| 2 | Violets for Your Furs | |

| 3 | Down Home | |

| 4 | Almost Like Being in Love | |

| 5 | Wee-Dot | |

| 6 | Too Close for Comfort |

Selections:

“Just Blues” (Sims)

For Collectors

This LP didn’t pique my interest until I saw an original pressing on the wall at an esteemed Manhattan record shop last fall. Though I was unfamiliar with the music, I knew of the record’s ‘holy grail’ status. Needless to say, I was intrigued. At this point in my time collecting I felt confident handling such an expensive piece, and when I removed the vinyl from the sleeve it was beautiful — Lexington Ave. labels, flat edge, deep groove, all the trimmings. When I got home later that evening I gave it a listen on Spotify and quickly realized how fun and animated the music was. Though I had never spent anywhere near the asking price on a record before, the thought that I may never see the record again eventually captivated my mind, so I arranged an in-store audition.

I set out with cash in hand, ready to make what I believed to be a respectable offer. When I got to the store, I took a more careful look at the record before it played. Visually it was beautiful with only some light scuffing. When side 1 began, the music sounded loud and present and I liked what I heard. The second song, the ballad “Violets for Your Furs”, was quieter though, and revealed light yet consistent surface noise. The owner said the record had been cleaned, which was a bit disconcerting in consideration of the noise I was hearing. I began listening more carefully, and by the time the needle got to trumpeter Jerry Lloyd’s solo on “Down Home”, the last song on the first side, the deal was dead, as inner groove distortion was evident. I thanked the owner for his time and left the shop a (much) wealthier person.

At this point I knew I loved the music, so I picked up the Classic Records reissue. It sounded great, but I still wanted to see if there was something I was missing out on that could only be provided by a younger, fresher master tape. So I sought out the copy you see here, an early ‘70s United Artists copy (technically the second ever pressing of the album). Ultimately, the master tape sounded similar with both pressings and I decided to keep the UA.

(Note: The following two paragraphs were updated June 2024.) At this point it is clear that at least some of these UA mono LPs were exported for sale in Japan, as many copies can still be found with Japanese “OBI” stickers. The common cut corners with these records signal either promotional use or discounted/no-returns status. Additionally, although these early ’70s Blue Note reissues are some of the earliest to not be mastered by Rudy Van Gelder, Liberty Records had begun using other mastering engineers as early as 1966. But who mastered many of these United Artists reissues remains a mystery.

Some of these US reissues are not sourced from the original tapes. According to Blue Note archivist Michael Cuscuna, United Artists would have been the first parent label to demand that Blue Note’s original master tapes be duplicated (sometimes with Dolby noise reduction) in the event that the tape was beginning to flake. (This is why original copies of classic Blue Note albums with Van Gelder mastering are so valuable: there is no debating that they were made using first generation tapes shortly after the recording sessions.) But this myriad of possibilities doesn’t seem to have much of an effect on the quality of this particular finished product, the results of which can be heard in the needledrops above.

For Music Lovers

To stand out in the testosterone-overrun world of instrumental jazz, it certainly didn’t hurt that German-born pianist Jutta (pronounced “Yoo-ta”) Hipp was a woman. That’s probably what esteemed jazz critic Leonard Feather was thinking in 1954 when he began nurturing the undiscovered talent. After hearing a friend’s recording of her, Feather booked studio time in Germany for the 29-year-old redheaded bopper (New Faces – New Sounds from Germany, Blue Note 5056), then arranged for Hipp to come to New York City in November 1955 for a residency at the Hickory House on East 52nd Street. The six-month stretch that followed proved quite an eventful time for the pianist. She was recorded on location by Blue Note in April (Jutta Hipp at the Hickory House, BLP 1515/6), and amongst the plethora of world-renowned jazz musicians whose acquaintance she had the pleasure of making, Hipp was reunited with tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims, whom she had originally jammed with on the Continent a few years back when Sims was on tour with bandleader Stan Kenton.

Hipp woud eventually be asked to assemble a combo for a Blue Note session at the label’s holy house of sound, engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s home recording studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. Sims would be recruited along with drummer Ed Thigpen, the backbone of Hipp’s Hickory House trio. Trumpeter Jerry Lloyd came along with Sims and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik entered the equation as well. Overseen by Alfred Lion, a fellow German native, the session commenced in late July 1956 and produced the entirety of the LP in a single day.

The band warmed up with a pair of ballads: the Matt Dennis-Tom Adair composition “Violets for Your Furs” (first recorded by Frank Sinatra two years prior), and the standard “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)”. The former took what was perhaps a nervous Hipp four takes to get through, and while the time constraints of the LP format wouldn’t allow the latter on to the original release, it would surface for the first time 40 years later along with George Gershwin’s “’S Wonderful” on the 1996 Connoisseur Series compact disc.

|

| Sims and Hipp rehearsing at Van Gelder Studio |

Hours later, by the time seven songs were laid to tape, the session was all but complete when Sims would have suggested the band riff on an up-tempo twelve-bar progression of his choosing. The result was “Just Blues”, and the track proved to be so much fun that it would later be chosen as the album’s opener. (In a review for All About Jazz, critic Chris M. Slawecki quipped, “Sims contributed the opening “Just Blues”, although he apparently couldn’t be bothered to title it,” which provokes the comical image of Lion turning to Sims for the title after the take with Sims shrugging and humbly replying, “Just blues.”)

The album would eventually make it to store shelves seven months later in February 1957. But by this time Hipp had mysteriously disappeared from the scene, and without star power to drive album sales, the sides wouldn’t be repressed until the glory days of hard bop were long over, rendering the original LP a figment to the vast majority of the jazz record collecting populous.

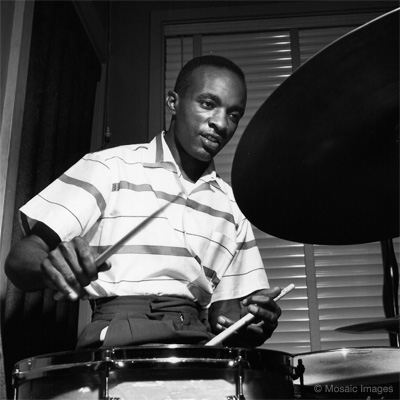

On first listen, the music here may sound a bit old-fashioned when held up to other cutting edge jazz albums recorded in 1956, but the consistently fun vibe of Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims proves difficult to deny. Sims would assume the unofficial role of leader that day, bringing a playful, infectious energy to the studio, and Hipp rose to the occasion despite known confidence issues. Thigpen, who would go on to form one-third of the legendary Oscar Peterson Trio, provides a steady, driving rhythm throughout, putting the soloists in the zone with inspiring momentum on more upbeat tunes like “Just Blues”, Lloyd’s “Down Home” and the J.J. Johnson composition “Wee Dot”.

|

| Drummer Ed Thigpen |

The recording itself is one of Rudy Van Gelder’s finest. By 1956 the engineer had finally backed off the quirky artificial spring reverb that hinders many of his earliest recordings, allowing listeners to hear the natural ambience of the Hackensack living room in all its makeshift glory. Soft, warm cymbals also define Van Gelder’s sound during this period, giving the music a unique, almost cartoony character. For the finishing touch, Reid Miles provided some of his most iconic design: a colorful, modern jumble of rectangles primitively imitating the keys of a piano (the cover has proven so iconic it has found a home in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City).

Sadly, this was the last time Hipp would enter a recording studio. At some point the pianist became jaded by the music industry, retreating to Queens to work in a textile factory. She returned to her first creative passion, painting, and lived alone there until 2003 when she passed away due to terminal illness. There are only a few recordings of the German phenom to be heard as a result, and we should be grateful for this particular shining example of her talents.

How They Heard It: Blue Note Records and the Transition from Mono to Stereo

Several years ago, when I first became a collector of vintage jazz records, I was confused. Original mono copies of albums from Blue Note’s classic catalog were significantly more expensive than their stereo counterparts, yet virtually all the talk online was of the original “stereo” master tapes for these sessions. Why then were the mono copies so much more valuable than the stereo copies if the albums were recorded to two-track tape?

I set out to find the answer, and soon discovered that there was a good amount of misunderstanding amongst audiophiles and record collectors regarding the methods of Blue Note’s exclusive recording and mastering engineer, Rudy Van Gelder. Realizing how historically and culturally important these recordings are, I decided to make a more formal study of the issue, and the results were published on the London Jazz Collector website in July of this year.

Shortly after publishing, I decided that the article could be made much more efficient, and last month London Jazz Collector published the revised version of the article. The new version is more concise and hopefully easier to understand. Click on the link below to check it out!

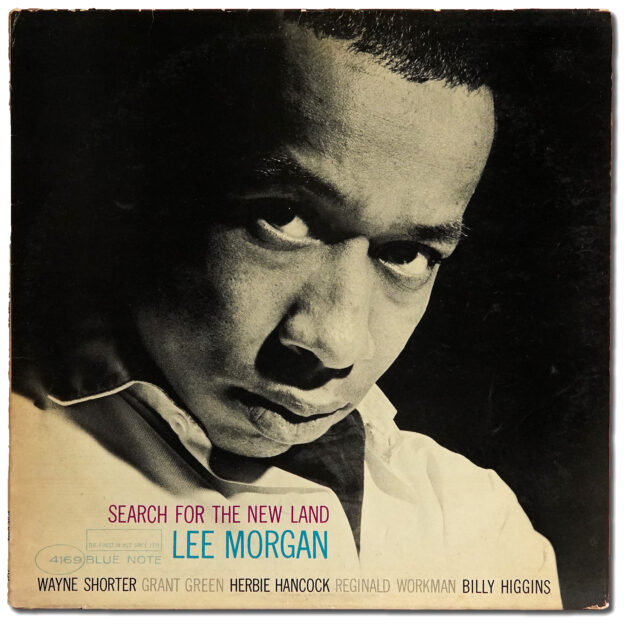

Vinyl Spotlight: Lee Morgan, Search for the New Land (Blue Note 4169) “Earless NY” Mono Pressing

- Second mono pressing circa 1966

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket

Personnel:

- Lee Morgan, trumpet

- Wayne Shorter, tenor saxophone

- Grant Green, guitar

- Herbie Hancock, piano

- Reggie Workman, bass

- Billy Higgins, drums

Recorded February 15, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released August 1966

| 1 | Search for the New Land | |

| 2 | The Joker | |

| 3 | Mr. Kenyatta | |

| 4 | Melancholee | |

| 5 | Morgan the Pirate |

Selection:

“Melancholee” (Morgan)

For Collectors

This record is especially hard to find with the Plastylite “P”, though it does exist. I have had good experiences with Liberty pressings though, so I’m not hung up on finding an original pressing of this album. The first copy I had, also a Liberty pressing, was cheap but it had a few loud pops and clicks, which prompted me to seek out this replacement, which I think was fairly graded VG+.

For Music Lovers

It’s difficult to discuss a Lee Morgan album without considering where and how it fits into the dramatic and tragic story of his life. At the age of 20, Morgan first recorded as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in October 1958 for the classic album Moanin’. His residency with Blakey would continue until the summer of 1961 when Morgan and fellow Philadelphian Bobby Timmons made the decision to retreat to their hometown for relief from the heroin-infested New York jazz scene. Morgan would only step in the studio once over the course of the next two years for producer Orrin Keepnews (Take Twelve, Jazzland 980), but would eventually make his official return to the New York recording scene in the fall of 1963 for a date with Hank Mobley (No Room for Squares, Blue Note 4149). After taking an uncharacteristic date with the progressive Grachan Moncur III the following month (Evolution, Blue Note 4153), Morgan recorded The Sidewinder in December 1963. The smash hit wouldn’t be released until the following summer, however. In the meantime, Morgan entered the studio again in February 1964 to record Search for the New Land, which would ultimately be shelved until 1966 – perhaps as a result of the tremendous commercial success of Sidewinder.

While Morgan and Shorter had been bandmates in The Jazz Messengers for years before Morgan’s hiatus, this would be the first of only a handful of occasions where the trumpeter would record with Herbie Hancock. (I was surprised to learn that this was only the second time that Shorter and Hancock had recorded together.) Billy Higgins returned from the Sidewinder date – which would prove to be the start of a lengthy partnership between he and Morgan – while Grant Green and Reggie Workman rounded out the sextet.

For all the Blue Note sessions Lee Morgan had led since he began recording for the label in 1956, this would only be the second where the entire program was penned by Morgan himself (The Sidewinder being the first). As such, Search for the New Land is a beautiful contemplation of the then looming and uncertain future of jazz. It is not a desperate exodus out of bop; it can be better likened to a child on the ocean’s shoreline standing knee-deep in the waves, hesitant to submerge themself in the water. Search thus pushes the boundaries of hard bop just enough to keep within the sub-genres inherent structure.

The album is consistent and cohesive. The dreamy, somber choruses of the title track are flanked by improvisational sections fashioning a minimal harmonic structure that compliments the modal leanings of Hancock and Shorter (this session would predict their uniting with Miles Davis as members of his “second great quintet” later that year). Hancock especially shines on the take with a crisp solo exemplifying his clear and acute thinking at the piano. “Mr. Kenyatta” bounces between moods in much the same way as the title track, swaying back and forth between feelings of angst and playfulness. And while The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings refers to the closing pair of songs as “more than makeweights” but “more off-the-peg” in comparison to the rest of the material, this ironically is my favorite sequence of the album. “Melancholee” is a gorgeously despondent composition that gives us a hard, honest look at the inner workings of Morgan, and the uplifting melody of “Morgan the Pirate” follows closely behind to conclude the album with an air of optimism.

One can’t help but wonder if the aforementioned session with Moncur had a profound impact on Morgan. Perhaps his experimentation at this time was actually a rebellion against the avant-garde manifesto, an attempt to push the boundaries of the institution of bop without succumbing to the full-blown chaos of free jazz. Either way, Search for the New Land is an expressive journey to the edges of an idiom, and it stands as an important work created at a pivotal crossroad in the evolution of the jazz art form.

Vinyl Spotlight: Blue Mitchell, The Thing to Do (Blue Note 4178) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1965 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket

Personnel:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet

- Junior Cook, tenor sax

- Chick Corea, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- Al Foster, drums

Recorded July 30, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released May 1965

Selection: “Step Lightly” (Henderson)

For Collectors

If you’ve read my first “Perspective” article here on Deep Groove Mono, you already know the story of how I acquired this record, which is special to me because it was the first vintage Blue Note album I ever heard that truly embodied the legendary “Blue Note sound”. And how about that cover? The symmetry, the cool blue on the dead black background, and the detailed shot of Blue’s hands on his trumpet make for a winning combination in my book.

For Music Lovers

I’m a huge Horace Silver fan, and I have always enjoyed the work of Blue Mitchell and tenor saxophonist Junior Cook as members of the Horace Silver Quintet. Mitchell had been working with Silver for four solid years the first time he entered the studio as a leader for Blue Note in August 1963 for a session including Joe Henderson and Herbie Hancock (for some reason, the recordings were shelved for nearly two decades). Two months later in the fall of ’63 though, Blue, Junior, and Quintet bassist Gene Taylor would have their last hurrah recording with Silver on a date producing two takes which would eventually find their way to Song for My Father. I haven’t read anything regarding the musicians’ parting of ways, but one can only guess it was peaceful, especially in light of the fact that Blue had jammed with Henderson, Cook’s replacement, before Silver.

Nine months later in the summer of 1964, Blue, 34 at the time, got Cook and Taylor together with a couple bright and budding musicians who would go on later to obtain global exposure with Miles Davis. 23-year-old Chick Corea had only recorded a handful of times when he arrived at Englewood Cliffs that day, and the 21-year-old Al Foster had yet to even set foot in a recording studio. But the pair rose to the challenge of this big-league outing with grace and poise, and their youthful energy ultimately steal the show on The Thing to Do.

If you think the head of the album opener, “Fungii Mama”, sounds zany or perhaps even corny, don’t let it deter you so quickly. Cook leads off with an inspiring solo, and Blue provides a fun improvisation of his own songwriting work. Corea eventually delivers a solo that is both fun and ambitious, and Foster follows with a challenging juxtaposition of the downbeat that causes the head to make a startling and exciting return. It’s a real treat to hear the young drummer’s rock-solid, driving latin rhythm throughout, and the tension created by each return to the bridge is a most welcome harmonic excursion.

My personal pick though is “Step Lightly”. The song was first recorded on the aforementioned 1963 date with Henderson and Hancock, but the overall vibe remains the same here. This track never really stood out to me until I recently heard it on a cloudy weekday afternoon off from work. The lazy tempo and bluesy melody complemented the mood so perfectly I instantly felt like I understood Henderson’s intentions as the song’s composer.

Sonically, this album is an example of Rudy Van Gelder at his best. The recording giant got a very nice piano sound here, and the natural reverberation of the Englewood Cliffs studio sounds heavenly, especially during Foster’s solo on “Fungii”. For those who don’t know, I’m a drum guy, and as such I recommend paying close attention to how tight and well-tuned Foster’s tom-toms sound here. (That’s one thing I love about classic jazz: the drum kits were made with care, the drummers took their craft seriously enough to tune their kits regularly, and you can hear the difference!)

Overall, I think the songwriting on this album is solid (Jimmy Heath’s title track included), and it gives us a rare glimpse of the vigorous, hungry duo of Corea and Foster on a straight-ahead bop date preceding their respective moves into free jazz and fusion. I personally need to be in the right mood to enjoy a record like The Thing to Do with its don’t-take-yourself-too-seriously-type attitude. But when I’m in that mood, these sides are as good as any.