- Original 1966 mono pressing

- “2-eye” labels

Personnel:

All but “Misterioso”, “Light Blue”, and “Evidence”:

- Charlie Rouse, tenor saxophone

- Thelonious Monk, piano

- Larry Gales, bass

- Ben Riley, drums

“Misterioso”, “Light Blue”, and “Evidence” only:

- Charlie Rouse, tenor saxophone

- Thelonious Monk, piano

- Butch Warren, bass

- Frankie Dunlop, drums

“Evidence” recorded May 21, 1963 at Sankei Hall, Tokyo

“Light Blue” recorded July 4, 1963 at Newport Jazz Festival, Newport, RI

“Misterioso” recorded December 30, 1963 at Lincoln Center, New York, NY

“I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” and “All the Things You Are” recorded November 1, 1964 at The It Club, Los Angeles, CA

“Bemsha Swing” recorded November 4, 1964 at The Jazz Workshop, San Francisco, CA

“Well, You Needn’t” recorded February 27, 1965 at Brandeis University, Waltham, MA

“Honeysuckle Rose” recorded March 2, 1965 in New York, NY

Originally released in 1966

Selection: “Light Blue” (Monk)

1. Some of Monk’s most inspired recordings were for Blue Note in the late ’40s and early ’50s. As a result, they are not high-fidelity and I don’t find myself seeking out older recordings like this on vinyl.

2. Though Monk’s recordings for Prestige are generally of outstanding quality in terms of both fidelity and performance, the sequencing of these recordings for Monk’s Prestige LPs is scattered in comparison to the original 10″ LP sequences, which make more sense to me.

3. I enjoy many of Monk’s Riverside releases but I’ve never found vintage Riverside pressings to be of a very high quality. I’ve owned a few but resold them shortly after acquiring them.

4. Much of Monk’s output for Columbia included songs he had already recorded for other labels in the past, and in most cases I prefer the older recording. No doubt, Monk’s Columbia recordings are of exceptionally high fidelity, but I do find that his playing on older albums sounds a little more inspired. I also don’t feel that the pinpoint accuracy of the Columbia recordings suits Monk’s music as well as the sonic signature of studios like Hackensack (Prestige and some Riverside) and Reeves (Riverside).

One of the exceptions to 4. above is this compilation of previously unreleased live material. Knowing that Monk felt his studio albums primarily served as advertisements for his live performances, I’ve taken a stronger interest in the pianist’s live albums. Although this album was released relatively close to the death knell of mono in 1964, and despite the fact that Columbia had been releasing brilliant-sounding stereo LPs for several years by that time, I still cherish the mono version of this album because the stereo mixes of Monk on Columbia fail to position the leader in the center of the stereo field.

This album has sentimental value to me because it served as my introduction to Monk when I borrowed my friend’s copy many years ago and this is the second original mono copy I’ve owned. The first was in pretty good shape but last year at the WFMU Record Fair I stumbled upon this copy in near-new condition, and for the asking price I couldn’t pass it up.

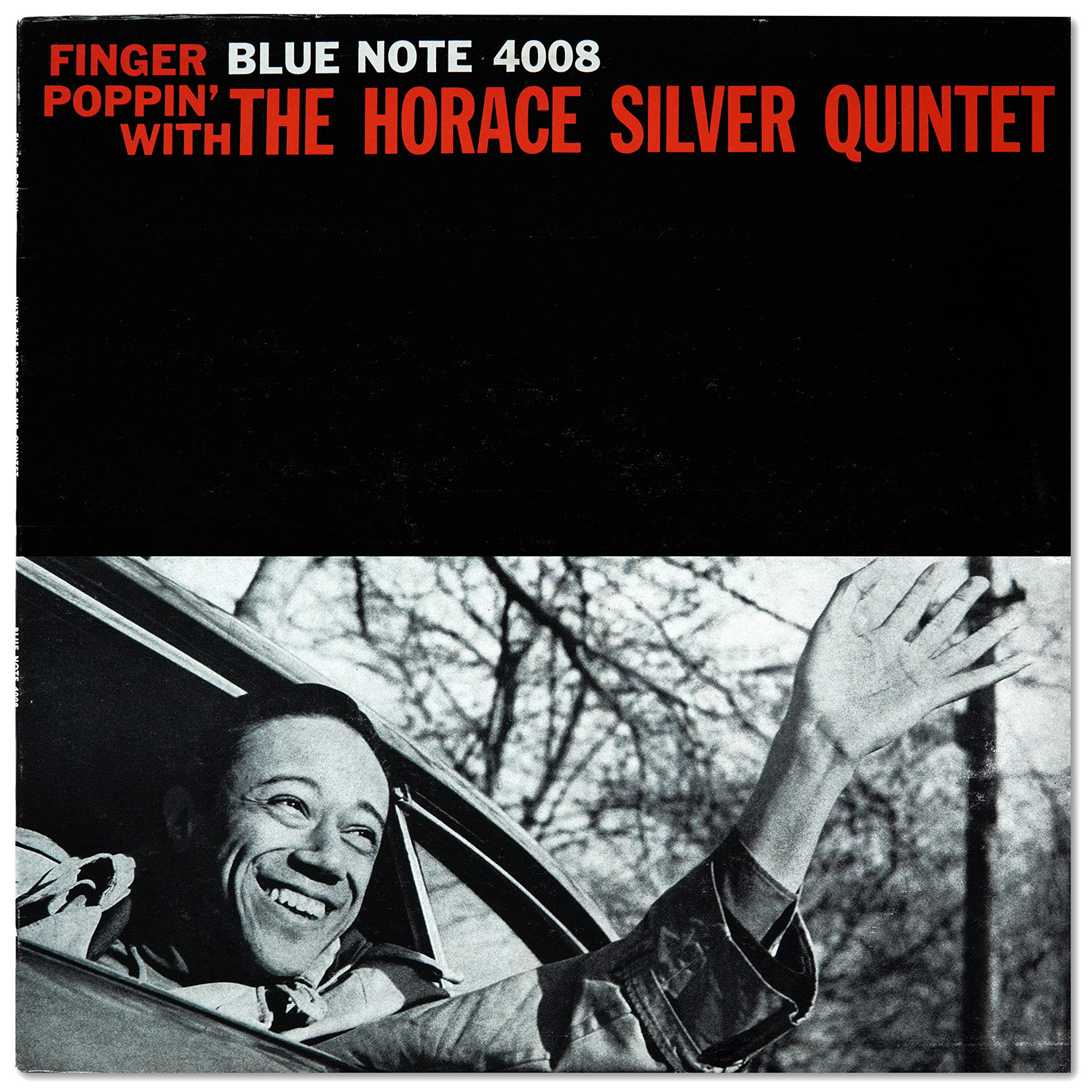

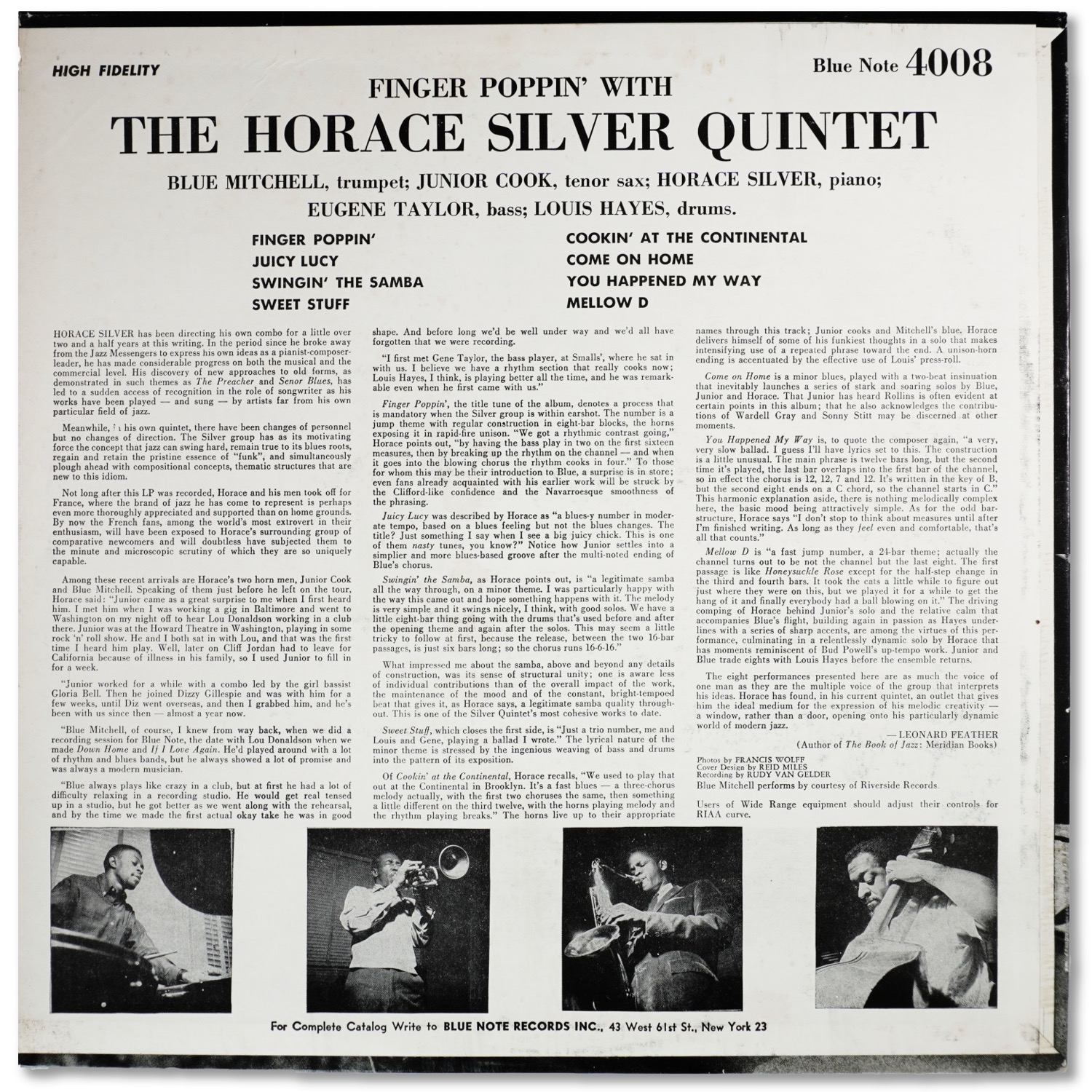

Vinyl Spotlight: Finger Poppin’ with the Horace Silver Quintet (Blue Note 4008) “Earless West 63rd” Mono Pressing

- “Earless” Liberty mono pressing ca. 1966

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet

- Junior Cook, tenor saxophone

- Horace Silver, piano

- Eugene Taylor, bass

- Louis Hayes, drums

Recorded January 31, 1959 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released February 1959

| 1 | Finger Poppin’ | |

| 2 | Juicy Lucy | |

| 3 | Swingin’ The Samba | |

| 4 | Sweet Stuff | |

| 5 | Cookin’ at the Continental | |

| 6 | Come on Home | |

| 7 | You Happened My Way | |

| 8 | Mellow D |

Selection: “You Happened My Way” (Silver)

After doing a little research, a controversial Music Matters online article led me to the incorrect conclusion that Blue Note albums recorded after Halloween 1958 were intended for stereo release despite their mono counterparts being more valuable. So I found an original stereo copy via eBay Buy It Now (this was one of the earliest Blue Note stereo albums with the rectangular gold “STEREO” sticker). This copy was overpriced, over-graded, and didn’t sound much better than my mono copy.

A couple years went by without my giving much thought to vintage jazz records when I decided to give the hobby another go. Around this time I got lucky winning an auction that ended on a weekday morning for a very fair price, and that record is being presented here. It has its fair share of pops and ticks but it’s managed to remain in my collection because it’s wear-free, it’s a first pressing, and the cover and labels are both in great shape.

Shortly after acquiring this copy through the mail, I debated on whether I preferred the stereo or mono version of this album. I remember liking how I could hear all of the nuances of Louis Hayes’ drum kit on the stereo copy, but I also didn’t like the way Horace Silver was crammed in the left-hand corner of the mix along with the trumpet. Both mixes had their pluses and minuses, but after doing a lot of research I came to the conclusion that this album was meant to be heard in mono so I sold my stereo copy largely on principle. (Someday I might buy another original stereo copy, though. The spread was super-wide and it was a real treat to hear Louis Hayes’ drumming in such isolation.)

It’s fun to reminisce about the early days of my collecting, back when it was all so new and fresh to me, back when I had as much first-hand experience with mono Blue Note originals as I had with unicorns, back when I would marvel at the value of mono Blue Note originals in the Goldmine price guide. It’s crazy to think about how far removed I am from that place today both in terms of knowledge and experience. I’m a wiser collector with the collection to prove it but I do miss that sense of wonder.

This isn’t one of my favorite Horace Silver albums but it does include some of my favorite songs. I played the title track over and over again when I was auditioning my various copies of this album and it stuck with me. To this day, the opener’s frantic bebop is an exhilarating listen and has ultimately served as my introduction to the legendary, bold mono sound of original Blue Note pressings. “Sweet Stuff” is in the Silver tradition of syrupy ballads like “Shirl” and “Lonely Woman”, though that doesn’t make it any less enjoyable of a listen. And despite it not standing out initially, “You Happened My Way” is a beautiful melancholy number that has since become a favorite Silver composition.

Someday I’d love to own a clean first pressing of this album, which in all likelihood wouldn’t cost me an arm and a leg. Luckily, Silver was a very popular artist in his day so I reckon that the chances of this happening are pretty good.

Vinyl Spotlight: The Horace Silver Quintet, Song for My Father (Blue Note 4185) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- Deep groove on side 1

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket without “Printed in U.S.A.”

Personnel:

All but “Calcutta Cutie”, “Lonely Woman”:

- Carmell Jones, trumpet

- Joe Henderson, tenor saxophone

- Horace Silver, piano

- Teddy Smith, bass

- Roger Humphries, drums

“Calcutta Cutie”, “Lonely Woman” only:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet (“Calcutta Cutie” only)

- Junior Cook, tenor saxophone (“Calcutta Cutie” only)

- Horace Silver, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- Roy Brooks, drums

“Calcutta Cutie” and “Lonely Woman” recorded October 31, 1963

All other tracks recorded October 26, 1964

All selections recorded at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released December 1964

| 1 | Song for My Father | |

| 2 | The Natives are Restless Tonight | |

| 3 | Calcutta Cutie | |

| 4 | Que Pasa | |

| 5 | The Kicker | |

| 6 | Lonely Woman |

Selection: “Lonely Woman” (Silver)

It makes sense that Song for My Father is part of many peoples’ introduction to the jazz genre. It is not only an essential part of the classic jazz canon, it is also a very accessible album. The minimalist structure of “Calcutta Cutie” and “Que Pasa” should cause just about anyone’s ears to perk up and listen. The album has everything: accessible tunes, a radio-friendly title track, two cooking sessions, and a gorgeous ballad. It certainly was one of the first albums I sought out. I first had the Rudy Van Gelder Edition CD, but when I started collecting jazz vinyl, this album was definitely near the top of my wish list.

The first time I came across an original pressing was at the Jazz Record Center in New York City. It was pretty exciting: I had just recently begun collecting and they had both original mono and stereo copies; I went for the mono. Though the record looked pretty darn clean when I bought it, to my dismay I later discovered that it suffered from audible groove wear. I bought another original mono copy on eBay with the same result before I got this copy via Buy It Now from a German seller. Although its visual condition is really only VG+, this copy is one of those rare instances where a vintage jazz record is scuffed up but free from groove wear and thus plays better than it looks.

My favorite song on this record is perhaps my favorite ballad of all time, “Lonely Woman”. It’s the last song on side 2, and because it’s the last song on the side I was faced with a particular dilemma. The phenomenon of inner groove distortion makes the innermost tracks on each side of a record more susceptible to groove wear, and this is exactly why my first two copies ended up for sale on eBay. Piano is an instrument especially prone to causing mistracing in the presence of groove wear, and on a ballad like this, that distortion is going to be easier to notice if it’s there. If you can find a Rudy Van Gelder-mastered original that’s free from groove wear like this one, the plus side to the engineer’s aggressive mastering techniques is that the music usually overpowers surface marks even in the most excessive of instances; listen above to hear the results.

Whereas my copy of this album has a deep groove on side 1 only, Fred Cohen’s Blue Note guide indicates that copies exist with deep grooves on both sides. But note that Cohen is very clear on page 77 of his guide when he explains the significance of deep grooves when evaluating the vintage of a Blue Note record:

“After a certain point, it can never truly be known whether similar pressings for the same record, whose only difference is the presence or absence of a deep-groove on one, both, or neither labels, is actually the original FIRST pressing. But since collectors have a natural bias for any detail that suggests an early or original issue, the presence of a deep-groove has been treated in this guide as an indication of an original, but ONLY an indication.”

Each of us is free to agree or disagree with him (I happen to think his scientific approach to the issue is exactly right) but I discourage the interpretation of the deep groove data in his guide as a definitive end-all-be-all as to what constitutes a first pressing for Blue Note albums released after the appearance of the first non-deep groove copies in 1961. There is no hard evidence suggesting that either deep groove or non-deep groove pressings of these albums always came first. For someone like myself, this means that in the event that all the other appropriate indicators are there, both deep groove and non-deep groove pressings should be considered first pressings. So if you have a copy of this album with the Van Gelder stamp and the “P” but no deep grooves, my advice is to consider it a first pressing.

The sound of this album is characteristic of Rudy Van Gelder’s work in the mid-1960s. As early as 1963 (see Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder), one can hear Van Gelder pushing his compressors harder than ever, resulting in a saturated, thick sound. Horns meld together like glue, piano notes come thundering down like hammers, and drums have an in-your-face presence where each and every nuance is amplified to cut through the mix. Of the sides presented here, “Song for My Father” embodies this sound the most.

This album is a bonafide classic. It is yet another Blue Note staple filled with brilliant music, an album that beckons to be listened to from start to finish every time.

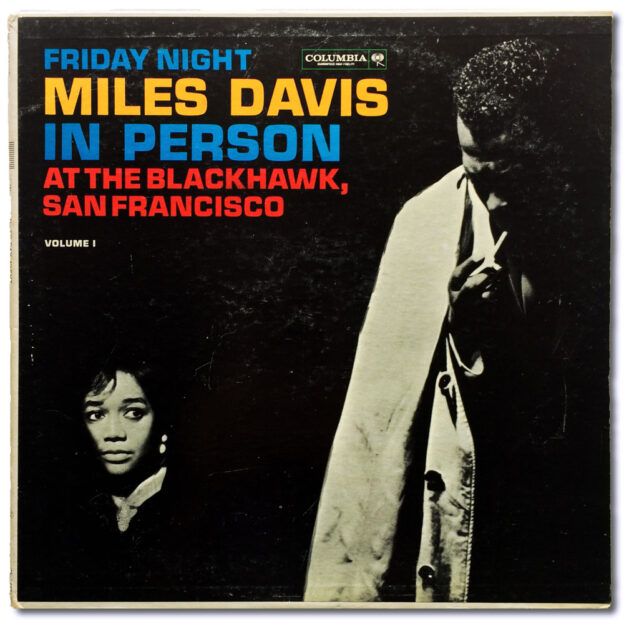

Vinyl Spotlight: Miles Davis In Person at the Blackhawk (Columbia 1669/1670) “6-Eye” Mono Pressings

Friday Night (CL 1669):

- Original 1961 mono pressing

- “Six-eye” labels

Saturday Night (CL 1670):

- Second mono pressing circa 1961-1962

- “Six-eye” labels

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- Hank Mobley, tenor saxophone

- Wynton Kelly, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Jimmy Cobb, drums

Recorded April 21-22, 1961 at the Blackhawk, San Francisco, California

Originally released September 1961

| 1 | Walkin’ | |

| 2 | Bye Bye Blackbird | |

| 3 | All Of You | |

| 4 | No Blues | |

| 5 | Bye Bye (Theme) | |

| 6 | Love I’ve Found You | |

| 7 | Well You Needn’t | |

| 8 | Fran-Dance | |

| 9 | So What | |

| 10 | Oleo | |

| 11 | If I Were a Bell | |

| 12 | Neo |

Selections:

“Walkin'” (Carpenter)

“So What” (Davis)

My Friday Night copy is considered an original pressing by most collectors but my Saturday Night copy is not due to the “CBS” marking on the labels. This is where I diverge from the record collecting consensus. I would agree that the CBS copy is not a first pressing but I would argue that there’s nothing wrong with referring to it as an “original pressing”. Being as specific as possible seems the honorable thing to do when it comes to selling, but my feeling is that in everyday conversation any copy of an album that would have been released in the era the album was originally released can rightfully be called an original (certainly, “in the era” is open to interpretation). Seeing that my CBS copy of Saturday Night was in all likelihood pressed in either the same year or the year after a first pressing, I don’t hesitate to think of this as an “original pressing”.

Live recording is by and large a more challenging endeavor when compared to the higher degree of control typically obtained in a recording studio. That being said, this Miles Davis album is an exceptional example of a live recording. Every instrument has its own space, even in mono, and the level of detail and accuracy here is a welcome break from the smeared, distorted sound of many live albums. Not only does Jimmy Cobb’s drum kit sound incredible here, his playing has a captivating and energetic sense of forward motion that seems to predict Tony Williams’ inclusion in Davis’ lineup shortly after. These albums also present a rare opportunity to hear how tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley, a mainstay of Blue Note records, holds up under the intense scrutiny of the date’s superstar bandleader.

Vinyl Spotlight: The Horace Silver Quintet, The Tokyo Blues (Blue Note 4110) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1962 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket without “Printed in U.S.A.”

Personnel:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet

- Junior Cook, tenor saxophone

- Horace Silver, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- John Harris, Jr., drums

Recorded July 13-14, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released November 1962

| 1 | Too Much Sake | |

| 2 | Sayonara Blues | |

| 3 | The Tokyo Blues | |

| 4 | Cherry Blossom | |

| 5 | Ah! So |

Selection: “Sayonara Blues” (Silver)

This record is one of the finest examples of engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s original mono mastering work in my entire collection. Granted, I only own a handful of these, but I’ve had dozens more pass through my hands over the years and this is definitely one of the good ones. What makes it one of the best? Condition. Since so many original Blue Notes seem to have suffered groove damage at the hands of primitive playback equipment, I have found that the key ingredient in a stellar-sounding original is the extent to which past usage has left its mark on the record. Not only does this record look amazing 55 years after it would have been taken home from the store, the sound is still fresh and vivid — the way you might expect it to have sounded back in 1962.

It’s possible that bandleader Horace Silver’s choice of a Far Eastern theme influenced drummer John Harris Jr.’s choice of a more minimal, sparse style of playing throughout, which gives each instrument plenty of room to breathe and cut through. (Less percussive energy also provides less of a challenge when getting the music onto tape and into the grooves of the wax.) The standout moment here is Silver’s four-and-a-half-minute romp on the keys in “Sayonara Blues”, a solo with trance-like qualities reinforced by a two-chord, left-hand mantra.

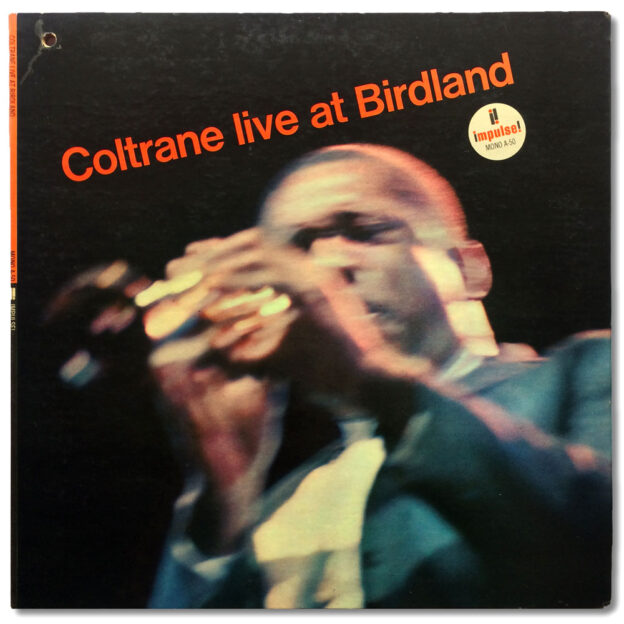

Vinyl Spotlight: John Coltrane, Coltrane Live at Birdland (Impulse 50) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “ABC-Paramount” on labels

- “VAN GELDER” in dead wax

Personnel:

- John Coltrane, tenor and soprano saxophone

- McCoy Tyner, piano

- Jimmy Garrison, bass

- Elvin Jones, drums

All but “Alabama”, “Your Lady” recorded October 8, 1963 at Birdland, New York, New York

“Alabama”, “Your Lady” recorded November 18, 1963 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Originally released April 1964

Selection: “Afro Blue” (Coltrane)

Generally speaking, I don’t know the Impulse catalog very well, and accordingly I have a harder time keeping track of the ‘first-first pressing’ melee associated with the label. Thus I’m not really sure if this is a ‘first-first pressing’ or just a ‘first pressing’, but it has the Van Gelder stamp of approval and, more importantly, it plays through without the hideous artifacts of groove wear so I’m a happy camper. This copy had a lot of light scuffs when I first looked at it, which is probably what kept the price down, but by the time I got it home and gave it a listen I was happy to find that this was a rare case of a record ‘playing better than it looked’. I am so inspired by the intensity with which John Coltrane played the soprano saxophone during this time period, and “Afro Blue” is a fine example of that passion and vigor.

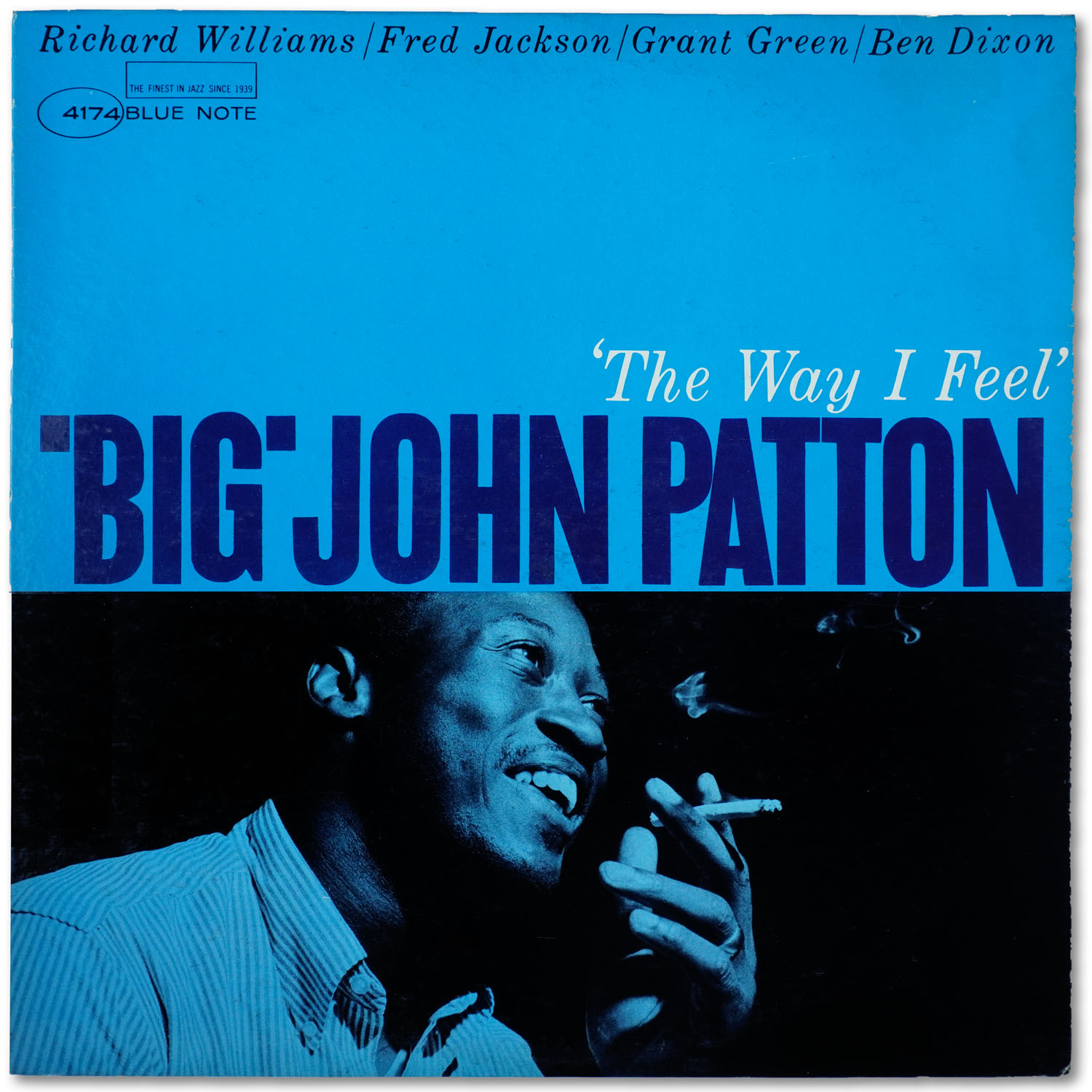

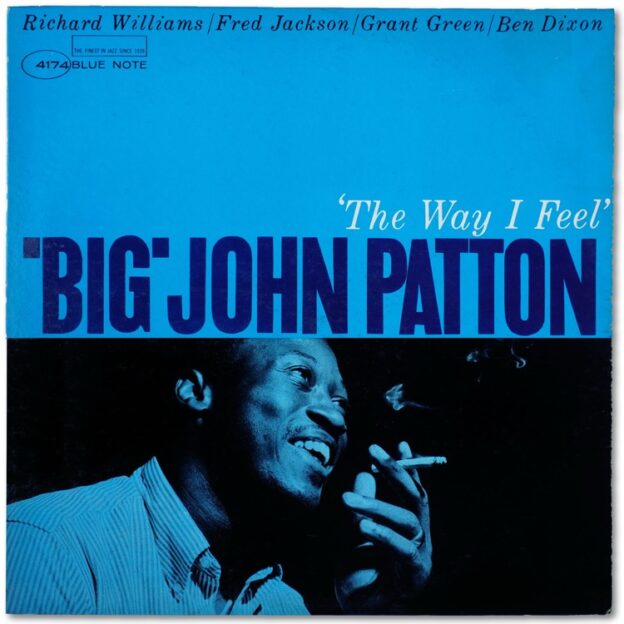

Vinyl Spotlight: Big John Patton, The Way I Feel (Blue Note 4174) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Richard Williams, trumpet

- Fred Jackson, tenor & baritone saxophones

- Grant Green, guitar

- John Patton, organ

- Ben Dixon, drums

Recorded June 19, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released October 1964

| 1 | The Rock | |

| 2 | The Way I Feel | |

| 3 | Jerry | |

| 4 | Davene | |

| 5 | Just 3/4 |

Selection:

“The Rock” (Patton)

A rare record in any format, this is the genuine article right here: Van Gelder stamp, Plastylite “P”, mono. After its original release in 1964, The Way I Feel was never reissued on LP or CD in the United States, and it has only been reissued twice in Japan on CD. The reason for the scarce number of reissues could be related to the fact that my Capitol Vaults digital copy has heavy audible tape damage in a couple of spots, which was a major reason I was so persistent in seeking out a vintage copy. However, I’ve owned a few copies of this over the years, all with original Van Gelder mastering, and I’m convinced that the mild distortion I hear on Richard Williams’ loudest trumpet blasts was baked into the original master lacquer disk and is therefore present on every copy. As much of an RVG fan-boy as I am, the truth is that the engineer was obsessed with obtaining a superior signal-to-noise ratio in his work and in the process mastered (and recorded) a little too hot at times.

This is one of my favorite Blue Note albums. It is definitely in my top five, partly because it is so consistent. When I first got into jazz, I followed a lot of ignorant stereotypes, one of them being that jazz with an organ isn’t “real jazz”. But John Patton looked so damn cool on this album cover that I had to give it a try, and it was undeniable how jazzy, soulful, and funky this record was all at once. John Patton’s music is lighthearted and occasionally funny, and the leader clearly succeeds at bringing those qualities out of his sidemen here (saxophonist Fred Jackson’s solo on “The Rock” is a good example). The title track’s laid-back groove breaks up the soulful tempo of the first side by strutting at the pace of a crawl, and though “Davene” sounded a bit hokey to me at first, I have since realized it to be a beautiful ballad that is now a favorite.

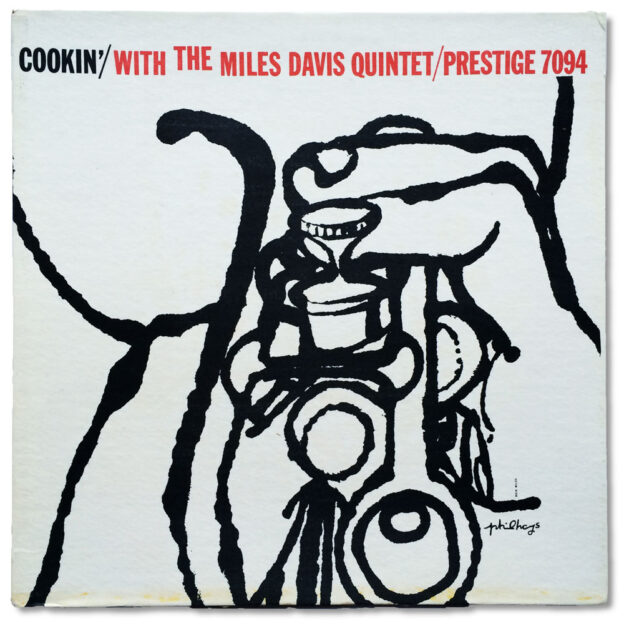

Vinyl Spotlight: Cookin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet (Prestige 7094) Second “Bergenfield” Pressing

- Second pressing circa 1958-1964 (mono) with small Abbey pressing ring

- “Bergenfield, N.J.” on both labels

- Deep groove on both sides

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Red Garland, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

Recorded October 26, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released in 1957

| 1 | My Funny Valentine | |

| 2 | Blues by Five | |

| 3 | Airegin | |

| 4 | Tune Up/When the Lights Are Low |

Selections:

“My Funny Valentine” (Rodgers)

“Tune Up” (Davis) / “When the Lights are Low” (Carter)

I found this record several years back at the first WFMU record fair I ever attended in New York City. It’s not an “original original” pressing in the sense that it lacks the “NYC” address on the labels, but it’s still made from original Van Gelder mastering. On the ballad “My Funny Valentine” especially, you should be able to hear that this is a very clean copy I was fortunate to find for the price I paid.

Much of what I might say about the history of this album I’ve already said in my review of Davis’ ‘Round About Midnight, which shares the same lineup. I originally bought this record mainly because it was a vintage copy in great shape and because I love this version of “My Funny Valentine”, but I eventually came to appreciate the entire second side of the album just as much (“Blues by Five” remains a ho-hum listen for me). Philly Joe Jones’ drum kit sounds thunderous here, and overall we get a glimpse of engineer Rudy Van Gelder in one of his finest hours at his Hackensack studio.

It would appear that this album and Relaxin’ (Prestige 7129) are the two most popular LPs of the four that Davis’ First Great Quintet recorded for Prestige, the others being Workin’ (Prestige 7166) and Steamin’ (Prestige 7200). I find something to like in all of them, but Cookin’, the first of the four to be released, is definitely my favorite. All four albums were recorded on just two dates in 1956. Renowned audiophile mastering engineer Steve Hoffman has claimed in his online forum that Van Gelder did a better job of recording the second date (which just so happened to produce all the takes present on Cookin’), claiming that Van Gelder made excessive use of spring reverb on the earlier of the two dates; I can’t say I agree. I think Cookin’ has the best program start to finish but I think all four albums are representative of how brilliant Van Gelder was under the restrictions of the mono format.

Vinyl Spotlight: Miles Davis, ‘Round About Midnight (Columbia 949) Original Pressing

- Original 1957 pressing

- “Six-eye” labels

- Deep groove on both sides

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- John Coltrane, tenor saxophone

- Red Garland, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

All tracks recorded at Columbia 30th Street Studio, New York, NY

“Ah-Leu-Cha” recorded October 26, 1955

“Bye Bye Blackbird”, “Tadd’s Delight”, “Dear Old Stockholm” recorded June 5, 1956

“‘Round Midnight”, “All of You” recorded September 10, 1956

Originally released March 1957

| 1 | ‘Round Midnight | |

| 2 | Ah-Leu-Cha | |

| 3 | All Of You | |

| 4 | Bye Bye Blackbird | |

| 5 | Tadd’s Delight | |

| 6 | Dear Old Stockholm |

Selections:

“Ah-Leu-Cha” (Parker)

“Bye Bye Blackbird” (Dixon-Henderson)

For Collectors

Technically the third copy of this I’ve owned, my first copy was acquired on eBay, overpriced, and in rough shape. The second wasn’t much better, but this copy, acquired at the WFMU Record Fair in New York City a few years ago for a very reasonable price, is in fantastic condition, as you will hear!

Original pressing all around — I don’t personally get caught up in the matrix code game. For labels like Columbia, a matrix code can be used to identify the stamper and other metal parts used to press a particular copy of an album. The idea is that the quality of these parts deteriorates to some degree as each part is used in the manufacturing process, and thus that copies fashioning lower part numbers in the inner run-out section of each side have the potential to sound better (for more info on the vinyl manufacturing process, check out Deep Groove Mono’s links page).

From the information I’ve gathered, however, this difference will typically be so minuscule that it would be difficult to hear the difference between two records made from different parts (provided both copies were sourced from the same master lacquer disk). This is why I’ve chosen to stay away from the matrix code melee. In any event, for all you stamper geeks out there, this particular copy of Miles Davis’ classic ‘Round About Midnight was made from a “1C” stamper for side 1 and a “1A” stamper for side 2.

For Music Lovers

“The First Great Miles Davis Quintet” would have begun formulating around spring 1955 when pianist Red Garland and drummer Philly Joe Jones first joined the trumpeter for a recording session at Van Gelder Studio in Hackensack, New Jersey (The Musings of Miles, Prestige 7014). A few months later, bassist Paul Chambers and the harmonically curious yet ever-precise tenor saxophonist John Coltrane would complete the combo.

In addition to leading his new band, Miles was simultaneously eager to make the move from Prestige to Columbia Records. But the rising star still owed Prestige label head Bob Weinstock four more albums under contract. So before Columbia could release any material under the Davis moniker, Miles would need to fulfill his agreement with Weinstock. What then commenced in 1956 for the newborn quintet was a mash-up of Prestige and Columbia dates, all of which have since been heralded as classics.

‘Round About Midnight, Davis’ Columbia Records debut, was recorded in three sessions between October 1955 and September 1956 at Columbia’s historic 30th Street Studio in New York City. Many of you will already be familiar with the legendary sound of this studio. I find the sound on this particular album to be more immediate and up-front than the roomier sound heard on later Miles albums recorded here (Kind of Blue, for example). Nonetheless, the cathedral-turned-studio’s sonic blueprint is committed to tape here and the results are simply gorgeous.

|

| Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio |

Davis’ inaugural Columbia release is a highly consistent effort. On the album’s second tune, Miles takes Charlie Parker’s “Ah-Leu-Cha” at a faster tempo than the composer did on his own leisurely-paced 1948 recording (yet nowhere near as fast as Davis did at Newport in 1958), and though the leader opts for the bolder sound of an open horn here and on “Tadd’s Delight”, Davis’ signature muted trumpet sound dominates the album and is ultimately immortalized on ‘Round About Midnight. (It’s a shame that the quintet’s version of “Sweet Sue, Just You” didn’t make it to the original album release — a stellar take that could have only been left off as a practical matter of space — though fortunately it does appear on the 2001 Sony Legacy CD reissue.)

No sooner than alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley joined the group in early 1958 did Red Garland leave, unable to tolerate the leader’s sky-high standards. Jones would soon follow, and the First Great Quintet’s short reign would come to a close after the recording of Milestones. ‘Round About Midnight is thus one of the few examples of this iconic ensemble’s explosive power, and the album has stood the test of time as a rare combination of brilliance and accessibility equally fitting for attentive listening and unwinding.

Vinyl Spotlight: The Prestige Jazz Quartet (Prestige 7108) Original Pressing

- Original 1957 pressing

- “446 W. 50th ST., N.Y.C.” on both labels

- Deep groove on both sides

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Teddy Charles, vibraphone

- Mal Waldron, piano

- Addison Farmer, bass

- Jerry Segal, drums

Recorded June 22 and June 28, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

| 1 | Take Three Parts Jazz | |

| 2 | Meta-Waltz | |

| 3 | Dear Elaine | |

| 4 | Friday the 13th |

Selection: “Dear Elaine” (Waldron)

For Collectors

Prestige released numerous LPs in the late ’50s, many of which stand today as interesting mixes of rarity, low demand, and musical excellence. This album is one example of that. I first heard it on Spotify and instantly took to it, but the master tape had noticeably degraded by the time of its digital mastering. So it became a priority of mine to seek out an original. One weekend afternoon last winter I was checking out a Swedish jazz dealer’s website and there it was, an original pressing touting VG++ condition. The asking price was a tad high so I talked the seller down a little and about ten days later the LP arrived at my doorstep. Quiet vinyl is a must for quiet music like this, and as you will be able to hear in the clips above, this one’s definitely a keeper.

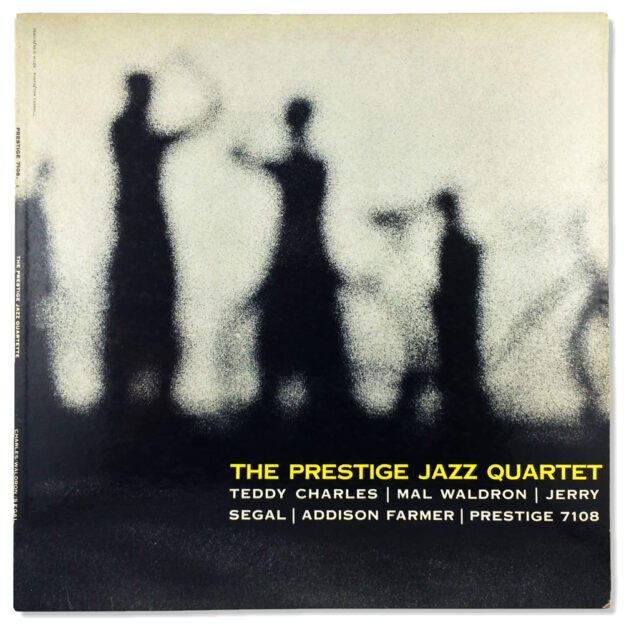

I was instantly a fan of the album art as well, which portrays a serene scene of silhouettes that to me appear to be practicing tai chi. What connection the cover is intended to have with the music I do not know, though I do find that its grey, clouded imagery complements the mood of the music quite well.

For Music Lovers

A pair of forward-thinking composers, Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron first recorded together in January 1956 for Atlantic Records release 1229, The Teddy Charles Tentet. A year later they collaborated on five albums in just as many months, four of which were recorded for Bob Weinstock’s Prestige and New Jazz labels (Olio, Prestige 7084; Coolin’, New Jazz 8216; Teo, Prestige 7104). The last album in the run is presented here, captured on two dates in late June 1957.

The soft timbres of The Prestige Jazz Quartet convey a calming mood throughout, even during the more uptempo moments. The album has experimental leanings that weren’t yet trendy in 1957, but the sparse solos hardly beg for the listener’s attention. The quartet arrangement with vibraphone makes for a spacious atmosphere that lends itself well to the nuances of the vibes. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder has also set the drums further back in the mix than usual, making even more room for the dreamy echoes of the vibes to resonate.

The program begins with a trio of movements penned by Charles (“Take Three Parts Jazz”), followed by a pair of Waldron compositions (“Meta-Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”) and concluding with a lesser-known Thelonious Monk tune, “Friday the Thirteenth”. “Route 4”, the first third of Charles’ piece, is an ode to the highway traveled by hundreds of the Big Apple’s finest jazz musicians traveling to and from Van Gelder’s home studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. The piece’s other bookend, “Father George”, refers to another passageway between the city and Van Gelder’s, the George Washington Bridge. “Lyriste”, the title of the middle section, is an invented word of Charles’ crafting that joins ‘lyrical’ and ‘triste’. In accordance with the titles, perhaps Charles intended the piece to serve as a soundtrack for a somber commute back to the island after a long day of recording, where use of the word ‘triste’ might have been meant to suggest that trips to Van Gelder’s were for many of the musicians a welcome break from the routine of city life.

Accompanying Charles and Waldron are bassist Addison Farmer (twin brother of trumpeter Art Farmer) and drummer Jerry Segal. Segal avoids complicating things by playing with tasteful restraint throughout, and Farmer more than plays his part by delivering an impressive solo on “Meta-Waltz”. Side B begins with “Dear Elaine”, an apprehensive sprinkling of notes that seems to provide a window into the mind of a cautious courter. Closing the album, Waldron’s regular use of refrain on “Friday the Thirteenth” creates a comforting sense of familiarity that culminates in an inspired hammering of adjacent keys. (In the original 1953 recording of the tune, Monk is in his prime, rightly delivering an astonishing solo, though there’s something about hearing that melody played on the vibes that makes more sense to me than hearing it on Rollins’ sax…what do you think?)

Charles and Waldron would collaborate sporadically moving forward, but this would be the last time the entire ensemble would be in a recording studio together. Despite it being a short-lived, lesser-known experiment, the Prestige Jazz Quartet was a group of exceptional talent that deserves its rightful place in the storybook of modern jazz.

Epilogue

When I was preparing to take photos of the album jacket last week, I heard something jostling around inside, so I took a peek and to my surprise there was a small piece of paper inside with what appeared to be two interviews dated 1958 and typed in Swedish (the country the record came from upon my purchase). I then thought it would be cool to post a scan of the paper and maybe send out an S.O.S. for help translating it, then I thought of Google Translate and decided to do the translation myself, which I am presenting here.

The reviews would have originally been published in two Swedish magazines, Estrad (“Bandstand” in English) and OJ (“WOW”), and both were written by well-known Swedish jazz musicians: saxophonist/arranger Harry Arnold, whose resume included working with Quincy Jones, and pianist/composer Lars Werner. The original owner of the record must have been in the habit of typing up reviews for all the records they owned (perhaps to make up for the fact that they couldn’t read the English liner notes). Arnold seems the more opinionated of the two, possibly due to being more experienced and knowledgeable, though the way in which Werner has been charmed by the music resonates more with me. Through my amateur translation I also sense that Arnold’s review is surprisingly informal and that Werner was the better writer of the two (I also favored what I heard of Werner’s own music on YouTube).

For me, finding that piece of paper and reading the reviews felt like being transported back to the endlessly fascinating time that these records were made in, and I thought I’d share my experience with anyone who feels similarly nostalgic. I hope you enjoy!

Harry Arnold, Estrad (Bandstand), February 1958:

Harry Arnold

Of course I could try to make this into a pompous analysis of this record, but since it is said that honesty is best kept at a distance — all right, I do not have much profound to say about this record. Do not think that I condemn the whole thing because I absolutely do not; I’m just so damn precarious about it.

Perhaps the review will be more useful if I stick to the basics. The quartet consists of vibraphone, piano, bass, and drums, so it is tempting to draw parallels with the Modern Jazz Quartet. Here and there the style is similar, but the compositions are not in the “classical” spirit, as is usually the case with John Lewis and partners.

Side one is occupied by a work endowed “Take Three Parts Jazz”. It is a symphony in three movements with names “Route 4”, “Lyriste”, and “Father George”. In addition there is a song called “Meta-Waltz” on the same side.

On “Friday the Thirteenth”, which Thelonious Monk wrote, I think the whole thing suddenly begins to sound more natural, this may possibly be due to the fact that Monk has a truer sense of jazz when he composes than the other composers on the disc have?

I think pianist Mal Waldron stumbles too much at times, and the slow vibrato on the vibraphone affects my nerves in an unpleasant way. I think that the chord changes become one soporific grinding — but I appreciate the disc in a way, because I have a feeling Teddy Charles and the others have a bona fide interest in reinventing jazz without resorting to hysterical effects. It should also be noted that the solos are quite interesting at times.

Lars Werner, OJ (WOW), January 1958:

Lars Werner

In both name and composition, listeners will inevitably be tempted to compare this group with the Modern Jazz Quartet, which of course for a long time almost had a monopoly on sales in the vibraphone quartet market. However, the Prestige group’s music is of an entirely different character than MJQ’s: it is less stylized and lacks a certain coolness while spanning over a larger emotional register. There is certainly no equivalent in the Prestige Jazz Quartet to the personality that is John Lewis in MJQ, nor a soloist by Lewis’ standards, but Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron’s music proves capable of keeping the listener’s interest alive naturally, and the brilliant bassist Addison Farmer gives an intense and unfailing swing to everything.

To their credit, Charles and Waldron have been doing a lot of experimenting that sometimes has more in common with contemporary musical manifestations other than jazz. Here however, it seems that they have started from the rich ballad tradition found in jazz, and I feel they have found success with this approach.

Charles’ contribution, the tripartite “Take Three Parts Jazz”, contains much more tangible musical material than some of the earlier stuff he has done. The piece is highly successful, with tempo changes, solos, and themes emerging out of necessity, and the sense of a greater whole is never lacking.

Waldron’s two contributions, “Meta Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”, display an unconventional touch and much melodic finesse. Both works are well prepared, and fortunately they lack the sort of searching character that has so easily crept into many attempts to break jazz conventions.

Finally, Thelonious Monk’s four-beat composition “Friday the Thirteenth” provides an opportunity for longer solos from Charles, Waldron, and Farmer.

As a soloist, Charles is not as virtuosic as Milt Jackson — who is the only one he has to compare. Charles plays fewer notes but often gets an aphoristic clarity of melody, which makes him a musician I like to listen to.

Waldron seems to look for things other than melodic development as a soloist. He is more interested in piano percussion characteristics, and piano solos become more of a series of rhythmic figures, albeit rather monotonous at times.

The Prestige Jazz Quartet is still only a gramophone ensemble, and I am afraid that its music lacks the accessibility of MJQ. But this album should in the long run be of greater importance than, for example, MJQ’s last album, which gets a little stale after a while.