For Collectors

After a couple years of collecting on a budget, the reality of the situation starts to sink in: you won’t be acquiring a first pressing of a holy grail like Kenny Dorham’s Quiet Kenny any time soon.

What makes an album a holy grail? Simply put, a combination of being very rare and very in demand. More specifically, in the case of this overlooked album, it probably has a lot to do with the fact that it didn’t get a proper second U.S. pressing until this version, the 1986 Original Jazz Classics reissue. (According to Discogs, Prestige released a Dorham album in 1970 simply titled 1959 with different album art but the same track listing as the OJC reissue, which includes the originally unreleased “Mack the Knife”.) To give the original even more allure, the tendency for reissue producers to have an overwhelmingly strong preference for stereo has rendered the original the only mono version of this album ever released.

There’s always something about reissues causing them to fall short of the excitement an original provides. Though I avoided Original Jazz Classics reissues for a while for this reason, I eventually relaxed my naïve original pressing snobbery and began considering reissues of favorites that were much too expensive in their first pressing form. I then read about how OJC reissues were by and large considered to be of exceptional sound quality, with the earliest of them guaranteed to be all analog as well (my copy had the original shrink wrap complete with the long rectangular OJC sticker characteristic of OJC albums released in the mid-80s). So I gave these reissues a chance, and by and large they have lived up to my expectations. The artwork and packaging are hit or miss with OJCs, though I think they did a good job with this release, and the fact that the labels mimic those used for the original New Jazz LP is an added bonus.

There’s always something about reissues causing them to fall short of the excitement an original provides. Though I avoided Original Jazz Classics reissues for a while for this reason, I eventually relaxed my naïve original pressing snobbery and began considering reissues of favorites that were much too expensive in their first pressing form. I then read about how OJC reissues were by and large considered to be of exceptional sound quality, with the earliest of them guaranteed to be all analog as well (my copy had the original shrink wrap complete with the long rectangular OJC sticker characteristic of OJC albums released in the mid-80s). So I gave these reissues a chance, and by and large they have lived up to my expectations. The artwork and packaging are hit or miss with OJCs, though I think they did a good job with this release, and the fact that the labels mimic those used for the original New Jazz LP is an added bonus.

For Music Lovers

Shortly after I got into jazz, I came across the OJC CD reissue of Quiet Kenny at a local library, and going off the album’s 3.5-star rating in The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings and its elite status among collectors, I decided to give it a try. Though the music didn’t immediately draw me in, I soon grew to appreciate the minimal arrangement and the big, empty, dark sound of Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. I also have a leaning toward more gentle styles of playing, which, as the title suggests, this album epitomizes.

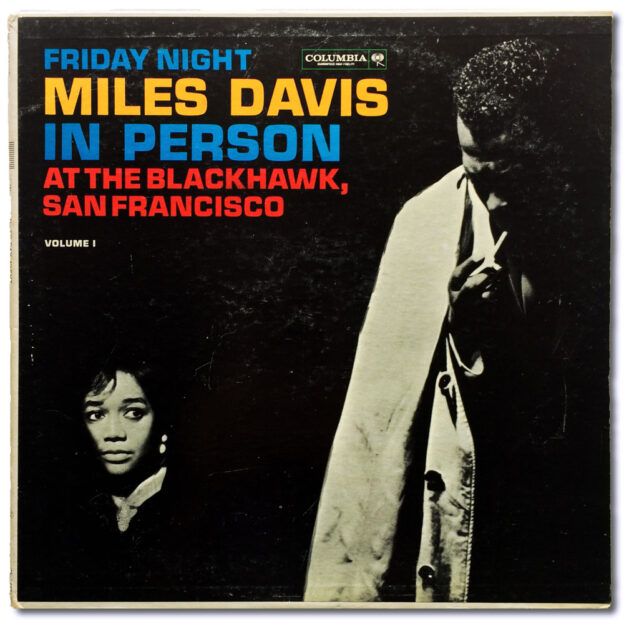

|

| Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey |

Quiet Kenny features three Dorham originals: “Blue Friday”, “Blue Spring Shuffle”, and “Lotus Blossom” — not to be confused with “Lotus Flower”, another Dorham composition, a ballad that premiered in 1955 on the ten-inch Blue Note LP Afro-Cuban (BLP 5065). Though “Blue Friday” appears here for the first time, “Lotus Blossom” had first been recorded by Riverside in 1957 with a piano-less quartet led by Dorham (2 Horns, 2 Rhythm, Riverside 255). As much as I enjoy the less busy rendition presented here, the driving pace of the Riverside version along with the harmony offered by Ernie Henry’s sax make the Riverside version tough to beat. “Blue Spring Shuffle” had already been laid to tape as well, appearing several months prior with the truncated title “Blue Spring” on the LP of the same name (Blue Spring, Riverside 297). In this case I hold the more sparse arrangement here in higher regard.

The first track on Quiet Kenny that stood out to me was “Lotus Blossom”, the gentle, uptempo opener. Art Taylor’s solo shines here, the gorgeous sound of which is a combination of the drummer’s well-crafted, finely-tuned kit, Van Gelder’s EMT reverb plate, and the natural ambience of the engineer’s custom-built cathedral-like studio. “My Ideal”, the next song in the sequence, has become one of my favorite jazz ballads. The other ballad, “Alone Together” follows close behind, and overall I find Quiet Kenny to be a solid listen with a clean, sweet sound throughout.

Mono vs. Stereo

Like many Blue Note albums released between the years of 1959 and 1962, every reissue of Quiet Kenny has been stereo despite the original release being exclusively mono. The best explanation for this would be that the album was recorded to two-track tape only. Since Van Gelder didn’t mix down to a separate master tape for mono releases in these instances (all mixing was done on the fly), reissue producers today would only be left with a two-track master tape to work with. And though it’s quite possible that these producers have unanimously preferred the stereo presentation to the mono, they may have also erroneously concluded that the album was monitored and mixed in stereo due to the absence of a mono master tape. But the fact that the inaugural release was strictly in mono strongly suggests the contrary. As a result, the only way to hear this music in mono today short of summing the channels of your stereo is to cough up $2,000+ USD for an original.

Offered here are both the stereo and mono presentations of the opening track for comparison (the mono obviously not being from an original pressing but the summing of the channels on my amplifier). Though the mono is cohesive where the stereo is somewhat disjoint and empty, I find the space created by the stereo spread too beautiful to collapse into a single channel.

There’s always something about reissues causing them to fall short of the excitement an original provides. Though I avoided Original Jazz Classics reissues for a while for this reason, I eventually relaxed my naïve original pressing snobbery and began considering reissues of favorites that were much too expensive in their first pressing form. I then read about how OJC reissues were by and large considered to be of exceptional sound quality, with the earliest of them guaranteed to be all analog as well (my copy had the original shrink wrap complete with the long rectangular OJC sticker characteristic of OJC albums released in the mid-80s). So I gave these reissues a chance, and by and large they have lived up to my expectations. The artwork and packaging are hit or miss with OJCs, though I think they did a good job with this release, and the fact that the labels mimic those used for the original New Jazz LP is an added bonus.

There’s always something about reissues causing them to fall short of the excitement an original provides. Though I avoided Original Jazz Classics reissues for a while for this reason, I eventually relaxed my naïve original pressing snobbery and began considering reissues of favorites that were much too expensive in their first pressing form. I then read about how OJC reissues were by and large considered to be of exceptional sound quality, with the earliest of them guaranteed to be all analog as well (my copy had the original shrink wrap complete with the long rectangular OJC sticker characteristic of OJC albums released in the mid-80s). So I gave these reissues a chance, and by and large they have lived up to my expectations. The artwork and packaging are hit or miss with OJCs, though I think they did a good job with this release, and the fact that the labels mimic those used for the original New Jazz LP is an added bonus.