- Original 1965 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket

Personnel:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet

- Junior Cook, tenor sax

- Chick Corea, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- Al Foster, drums

Recorded July 30, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released May 1965

Selection: “Step Lightly” (Henderson)

For Collectors

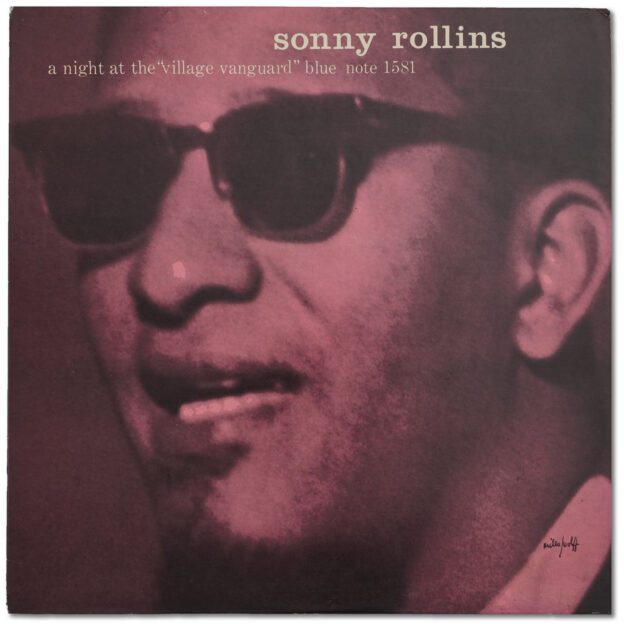

If you’ve read my first “Perspective” article here on Deep Groove Mono, you already know the story of how I acquired this record, which is special to me because it was the first vintage Blue Note album I ever heard that truly embodied the legendary “Blue Note sound”. And how about that cover? The symmetry, the cool blue on the dead black background, and the detailed shot of Blue’s hands on his trumpet make for a winning combination in my book.

For Music Lovers

I’m a huge Horace Silver fan, and I have always enjoyed the work of Blue Mitchell and tenor saxophonist Junior Cook as members of the Horace Silver Quintet. Mitchell had been working with Silver for four solid years the first time he entered the studio as a leader for Blue Note in August 1963 for a session including Joe Henderson and Herbie Hancock (for some reason, the recordings were shelved for nearly two decades). Two months later in the fall of ’63 though, Blue, Junior, and Quintet bassist Gene Taylor would have their last hurrah recording with Silver on a date producing two takes which would eventually find their way to Song for My Father. I haven’t read anything regarding the musicians’ parting of ways, but one can only guess it was peaceful, especially in light of the fact that Blue had jammed with Henderson, Cook’s replacement, before Silver.

Nine months later in the summer of 1964, Blue, 34 at the time, got Cook and Taylor together with a couple bright and budding musicians who would go on later to obtain global exposure with Miles Davis. 23-year-old Chick Corea had only recorded a handful of times when he arrived at Englewood Cliffs that day, and the 21-year-old Al Foster had yet to even set foot in a recording studio. But the pair rose to the challenge of this big-league outing with grace and poise, and their youthful energy ultimately steal the show on The Thing to Do.

If you think the head of the album opener, “Fungii Mama”, sounds zany or perhaps even corny, don’t let it deter you so quickly. Cook leads off with an inspiring solo, and Blue provides a fun improvisation of his own songwriting work. Corea eventually delivers a solo that is both fun and ambitious, and Foster follows with a challenging juxtaposition of the downbeat that causes the head to make a startling and exciting return. It’s a real treat to hear the young drummer’s rock-solid, driving latin rhythm throughout, and the tension created by each return to the bridge is a most welcome harmonic excursion.

My personal pick though is “Step Lightly”. The song was first recorded on the aforementioned 1963 date with Henderson and Hancock, but the overall vibe remains the same here. This track never really stood out to me until I recently heard it on a cloudy weekday afternoon off from work. The lazy tempo and bluesy melody complemented the mood so perfectly I instantly felt like I understood Henderson’s intentions as the song’s composer.

Sonically, this album is an example of Rudy Van Gelder at his best. The recording giant got a very nice piano sound here, and the natural reverberation of the Englewood Cliffs studio sounds heavenly, especially during Foster’s solo on “Fungii”. For those who don’t know, I’m a drum guy, and as such I recommend paying close attention to how tight and well-tuned Foster’s tom-toms sound here. (That’s one thing I love about classic jazz: the drum kits were made with care, the drummers took their craft seriously enough to tune their kits regularly, and you can hear the difference!)

Overall, I think the songwriting on this album is solid (Jimmy Heath’s title track included), and it gives us a rare glimpse of the vigorous, hungry duo of Corea and Foster on a straight-ahead bop date preceding their respective moves into free jazz and fusion. I personally need to be in the right mood to enjoy a record like The Thing to Do with its don’t-take-yourself-too-seriously-type attitude. But when I’m in that mood, these sides are as good as any.