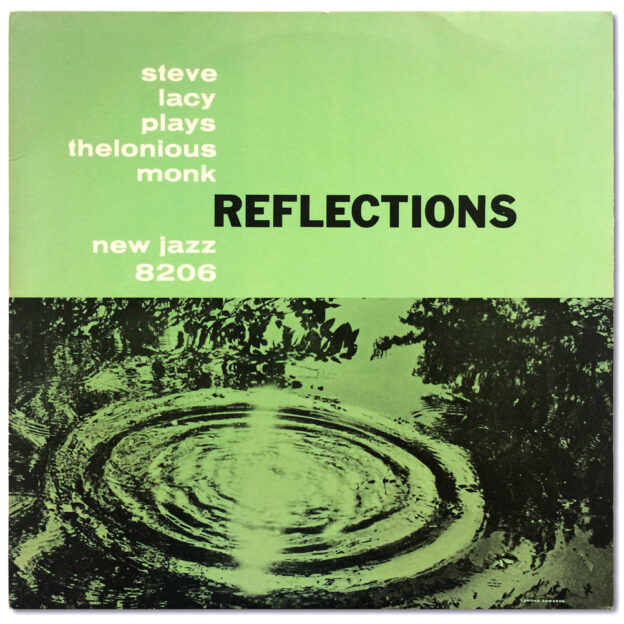

- Original Jazz Classics reissue circa 1983 (OJC-063)

- “GH” etched in dead wax (side 2 only)

Personnel:

- Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone

- Mal Waldron, piano

- Buell Neidlinger, bass

- Elvin Jones, drums

Recorded October 17, 1958 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released in 1959

Selection:

“Reflections” (Monk)

On this expedition I had the luxury of being able to preview records as I dug, and when I put this record on I was surprised by how much I liked what I was hearing. I quickly realized that Lacy had chosen more obscure, challenging Monk tunes for the album. Wynton Marsalis did something similar when I saw the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra pay tribute to Monk at Town Hall in New York City in 2016 and I admire the bravery that goes into making this kind of choice.

Not to discredit Lacy’s chops (of which he has plenty), just the combination of Monk’s music being played with soprano sax is a treat in and of itself. Lacy and session pianist Mal Waldron are clearly big fans of Monk’s, each having recorded Monk tunes numerous times throughout their careers. Considering how much I enjoy this album on top of its condition and the price I paid, this has become one of my favorite records in my collection.

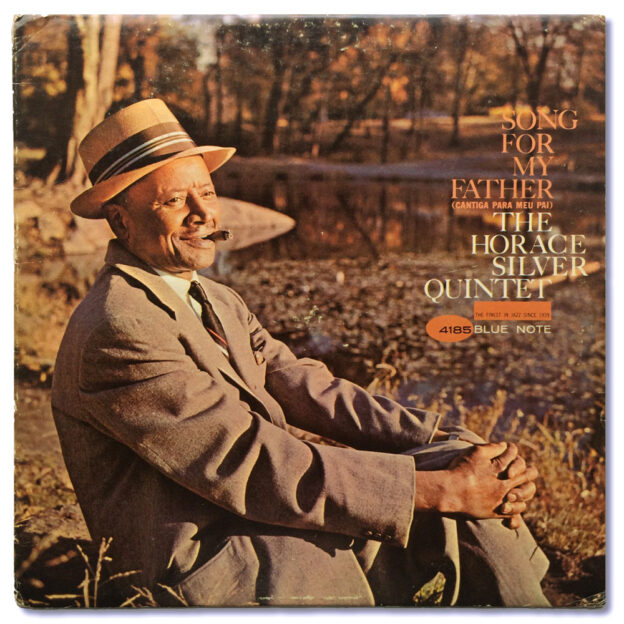

Vinyl Spotlight: The Horace Silver Quintet, Song for My Father (Blue Note 4185) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- Deep groove on side 1

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket without “Printed in U.S.A.”

Personnel:

All but “Calcutta Cutie”, “Lonely Woman”:

- Carmell Jones, trumpet

- Joe Henderson, tenor saxophone

- Horace Silver, piano

- Teddy Smith, bass

- Roger Humphries, drums

“Calcutta Cutie”, “Lonely Woman” only:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet (“Calcutta Cutie” only)

- Junior Cook, tenor saxophone (“Calcutta Cutie” only)

- Horace Silver, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- Roy Brooks, drums

“Calcutta Cutie” and “Lonely Woman” recorded October 31, 1963

All other tracks recorded October 26, 1964

All selections recorded at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released December 1964

| 1 | Song for My Father | |

| 2 | The Natives are Restless Tonight | |

| 3 | Calcutta Cutie | |

| 4 | Que Pasa | |

| 5 | The Kicker | |

| 6 | Lonely Woman |

Selection: “Lonely Woman” (Silver)

It makes sense that Song for My Father is part of many peoples’ introduction to the jazz genre. It is not only an essential part of the classic jazz canon, it is also a very accessible album. The minimalist structure of “Calcutta Cutie” and “Que Pasa” should cause just about anyone’s ears to perk up and listen. The album has everything: accessible tunes, a radio-friendly title track, two cooking sessions, and a gorgeous ballad. It certainly was one of the first albums I sought out. I first had the Rudy Van Gelder Edition CD, but when I started collecting jazz vinyl, this album was definitely near the top of my wish list.

The first time I came across an original pressing was at the Jazz Record Center in New York City. It was pretty exciting: I had just recently begun collecting and they had both original mono and stereo copies; I went for the mono. Though the record looked pretty darn clean when I bought it, to my dismay I later discovered that it suffered from audible groove wear. I bought another original mono copy on eBay with the same result before I got this copy via Buy It Now from a German seller. Although its visual condition is really only VG+, this copy is one of those rare instances where a vintage jazz record is scuffed up but free from groove wear and thus plays better than it looks.

My favorite song on this record is perhaps my favorite ballad of all time, “Lonely Woman”. It’s the last song on side 2, and because it’s the last song on the side I was faced with a particular dilemma. The phenomenon of inner groove distortion makes the innermost tracks on each side of a record more susceptible to groove wear, and this is exactly why my first two copies ended up for sale on eBay. Piano is an instrument especially prone to causing mistracing in the presence of groove wear, and on a ballad like this, that distortion is going to be easier to notice if it’s there. If you can find a Rudy Van Gelder-mastered original that’s free from groove wear like this one, the plus side to the engineer’s aggressive mastering techniques is that the music usually overpowers surface marks even in the most excessive of instances; listen above to hear the results.

Whereas my copy of this album has a deep groove on side 1 only, Fred Cohen’s Blue Note guide indicates that copies exist with deep grooves on both sides. But note that Cohen is very clear on page 77 of his guide when he explains the significance of deep grooves when evaluating the vintage of a Blue Note record:

“After a certain point, it can never truly be known whether similar pressings for the same record, whose only difference is the presence or absence of a deep-groove on one, both, or neither labels, is actually the original FIRST pressing. But since collectors have a natural bias for any detail that suggests an early or original issue, the presence of a deep-groove has been treated in this guide as an indication of an original, but ONLY an indication.”

Each of us is free to agree or disagree with him (I happen to think his scientific approach to the issue is exactly right) but I discourage the interpretation of the deep groove data in his guide as a definitive end-all-be-all as to what constitutes a first pressing for Blue Note albums released after the appearance of the first non-deep groove copies in 1961. There is no hard evidence suggesting that either deep groove or non-deep groove pressings of these albums always came first. For someone like myself, this means that in the event that all the other appropriate indicators are there, both deep groove and non-deep groove pressings should be considered first pressings. So if you have a copy of this album with the Van Gelder stamp and the “P” but no deep grooves, my advice is to consider it a first pressing.

The sound of this album is characteristic of Rudy Van Gelder’s work in the mid-1960s. As early as 1963 (see Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder), one can hear Van Gelder pushing his compressors harder than ever, resulting in a saturated, thick sound. Horns meld together like glue, piano notes come thundering down like hammers, and drums have an in-your-face presence where each and every nuance is amplified to cut through the mix. Of the sides presented here, “Song for My Father” embodies this sound the most.

This album is a bonafide classic. It is yet another Blue Note staple filled with brilliant music, an album that beckons to be listened to from start to finish every time.

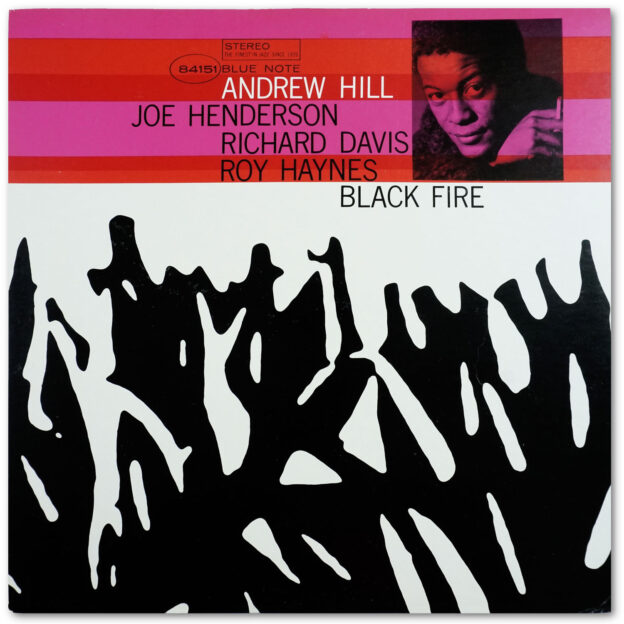

Vinyl Spotlight: Andrew Hill, Black Fire (Blue Note 84151) Liberty RVG Stereo Pressing

- Stereo Liberty reissue circa 1966-1970

- “A DIVISION OF LIBERTY RECORDS, INC.” on both labels

- “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Joe Henderson, tenor saxophone

- Andrew Hill, piano

- Richard Davis, bass

- Roy Haynes, drums

Recorded November 8, 1963 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released March 1964

| 1 | Pumpkin | |

| 2 | Subterfuge | |

| 3 | Black Fire | |

| 4 | Cantarnos | |

| 5 | Tired Trade | |

| 6 | McNeil Island | |

| 7 | Land of Nod |

Selections:

“Pumpkin” (Hill)

“Black Fire” (Hill)

First and foremost, I think this is one of the greatest album covers of all time. I love the juxtaposition of the bold strips of various red hues with the cartoony black-and-white illustration of fire beneath. Reid Miles’ cover design speaks volumes and yet again complements the music incredibly well.

From the time Andrew Hill arrived at Blue Note in 1963, it didn’t take long for the pianist-composer to venture “out” and away from bop. Hill first recorded for the label in September of that year with Joe Henderson (Our Thing, Blue Note 4152), then with Hank Mobley the following month (No Room for Squares, Blue Note 4149). Black Fire, Hill’s first album as a leader for Blue Note, was recorded in November 1963 and gives us an early glimpse at Hill loosely conforming to the higher degree of harmonic and melodic structure commonly found in bop. Blue Note would continue to document Hill’s musical explorations in the coming months, laying to tape Smokestack, Judgment!, then finally Hill’s avant-garde classic Point of Departure in March 1964 — the same month that Eric Dolphy recorded his landmark album Out to Lunch! for the label.

This album is about as far out as I’m willing go into the free jazz sea. I’m not a fan of free jazz and don’t know much about it, but from the little I do know I’m willing to say that Black Fire tows the line between post bop and the avant-garde. The sounds here tend to invoke a subtle feeling of panic, but much like another favorite mid-sixties quartet album of mine, Black Fire maintains a surprising degree of calm and quietude through all of the chaos. We also get to hear Roy Haynes on an uncommon Blue Note date and he doesn’t disappoint, demonstrating his patented pinpoint precision and tight snare drum work throughout.

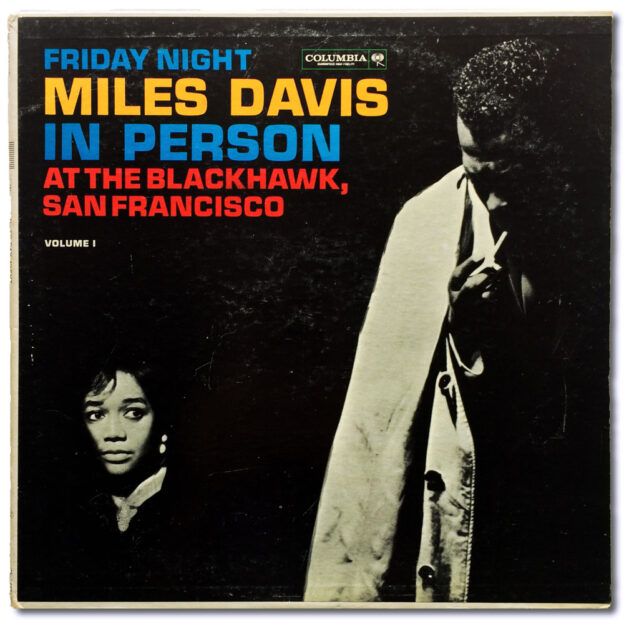

Vinyl Spotlight: Miles Davis In Person at the Blackhawk (Columbia 1669/1670) “6-Eye” Mono Pressings

Friday Night (CL 1669):

- Original 1961 mono pressing

- “Six-eye” labels

Saturday Night (CL 1670):

- Second mono pressing circa 1961-1962

- “Six-eye” labels

Personnel:

- Miles Davis, trumpet

- Hank Mobley, tenor saxophone

- Wynton Kelly, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Jimmy Cobb, drums

Recorded April 21-22, 1961 at the Blackhawk, San Francisco, California

Originally released September 1961

| 1 | Walkin’ | |

| 2 | Bye Bye Blackbird | |

| 3 | All Of You | |

| 4 | No Blues | |

| 5 | Bye Bye (Theme) | |

| 6 | Love I’ve Found You | |

| 7 | Well You Needn’t | |

| 8 | Fran-Dance | |

| 9 | So What | |

| 10 | Oleo | |

| 11 | If I Were a Bell | |

| 12 | Neo |

Selections:

“Walkin'” (Carpenter)

“So What” (Davis)

My Friday Night copy is considered an original pressing by most collectors but my Saturday Night copy is not due to the “CBS” marking on the labels. This is where I diverge from the record collecting consensus. I would agree that the CBS copy is not a first pressing but I would argue that there’s nothing wrong with referring to it as an “original pressing”. Being as specific as possible seems the honorable thing to do when it comes to selling, but my feeling is that in everyday conversation any copy of an album that would have been released in the era the album was originally released can rightfully be called an original (certainly, “in the era” is open to interpretation). Seeing that my CBS copy of Saturday Night was in all likelihood pressed in either the same year or the year after a first pressing, I don’t hesitate to think of this as an “original pressing”.

Live recording is by and large a more challenging endeavor when compared to the higher degree of control typically obtained in a recording studio. That being said, this Miles Davis album is an exceptional example of a live recording. Every instrument has its own space, even in mono, and the level of detail and accuracy here is a welcome break from the smeared, distorted sound of many live albums. Not only does Jimmy Cobb’s drum kit sound incredible here, his playing has a captivating and energetic sense of forward motion that seems to predict Tony Williams’ inclusion in Davis’ lineup shortly after. These albums also present a rare opportunity to hear how tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley, a mainstay of Blue Note records, holds up under the intense scrutiny of the date’s superstar bandleader.

Vinyl Spotlight: Herbie Hancock, Empyrean Isles (Blue Note 4175) UA RVG Stereo Pressing

- United Artists stereo reissue circa 1972-1975

- “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Freddie Hubbard, trumpet

- Herbie Hancock, piano

- Ron Carter, bass

- Tony Williams, drums

Recorded June 17, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released November 1964

Selections:

“One Finger Snap” (Hancock)

“Oliloqui Valley” (Hancock)

This is one of my favorite Herbie Hancock albums. It has a soft, gentle vibe that I return to time and time again when I want to listen to something quiet. The quartet with trumpet seems like the perfect minimal arrangement for this album, and even though I’m not the biggest Freddie Hubbard fan, I find that he fits in with the rest of the group like a glove here. I love the cover too. Reid Miles had a way of making album art reflect the music contained within, and with this album, the simple, out-of-focus image of shimmering water cast in a teal blue tint complements the music extremely well…even the pronunciation of the title has a calming sort of effect (“Em-PEE-ree-in”).

Although the album’s closing track, “The Egg”, ventures out a bit too far for my taste, the other three compositions are all favorites. “Cantaloupe Island” sounds like part three in a trilogy of soulful, radio-friendly Hancock compositions that began with “Watermelon Man” and “Blind Man, Blind Man”, but side 1 consists of sixteen of my favorite minutes in music. Eighteen-year-old (Eighteen!) Tony Williams’ drumming is fiery, imaginative and expressive. His kit sounds incredible here as well, especially his ride cymbal. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s spacious Englewood Cliffs studio had a way of making drum kits sound colossal when they needed to, which can be heard during Williams’ solo on “One Finger Snap”. Who would have ever thought that Blue Note darling Freddie Hubbard would pair with the rhythm section of Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet so well?

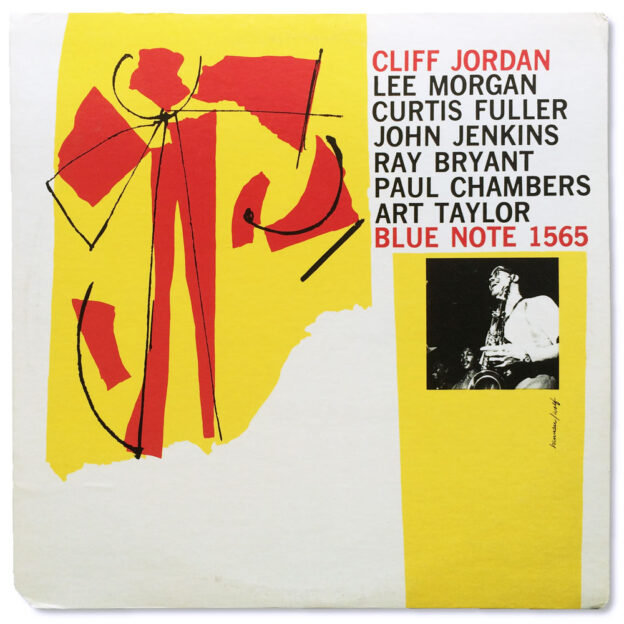

Vinyl Spotlight: Cliff Jordan (Blue Note 1565) UA Mono Pressing

- United Artists mono reissue circa 1972-1975

- “A DIVISION OF UNITED ARTISTS RECORDS, INC.” on both labels

Personnel:

- Lee Morgan, trumpet

- Curtis Fuller, trombone

- John Jenkins, alto saxophone

- Cliff Jordan, tenor saxophone

- Ray Bryant, piano

- Paul Chambers, bass

- Art Taylor, drums

Recorded June 2, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released October 1957

Selection:

“Blue Shoes” (Fuller)

Truth be told, these United Artists mono pressings from the early to mid ’70s are hit and miss, having heard more than one that suffered from significant non-fill problems. But this particular copy made it through that inconsistent manufacturing process unscathed. United Artists pressings also seem to have a gentler top end than a lot of modern audiophile reissues, which to some collectors makes them worth seeking out despite the difficulty in finding a quality copy.

This particular Cliff Jordan album also seems difficult to find in any format, which is why I jumped at the chance to buy it when it popped up on eBay. Discogs indicates that it has only been issued in the US twice on vinyl (originally in 1957 and this copy in the early ’70s) and never on CD. Though it has been reissued by Toshiba EMI in Japan once as an LP in 1984 (undocumented by Discogs) and three more times on compact disc there, these copies are hard to find in the states. And try you may, but you will not find these sides in any shape or form on iTunes or Spotify, making this a rare and special listen indeed.

Mono Vinyl Playback on a Modern Stereo Audio System

For someone who grew up in the stereo age, mono recordings can sound primitive and cramped when compared to the wider, more spacious aspects of stereo sound, and this heightened sense of realism is what ultimately won over the music-buying public back in the 1960s. But not only are some of history’s greatest music performances only available to us as mono recordings today, time has proven that the antiquated format possesses an allure that continues to charm music lovers of all ages. When done right, mono recordings demonstrate a great sense of cohesion and power, and the best of them also do an ample job of establishing a sense of depth and space. Though creating a mono recording that checks all of these boxes is no small technological feat, the great audio engineers of yesteryear have managed to hand down to us a treasure trove of work in mono that is both breathtaking and timeless.

If you’re a vintage jazz record collector, you’re probably aware of the fact that all mono LPs are compatible with today’s stereo audio equipment. While this is true, playing a mono record on a stereo audio system without making the proper adjustments leaves room for improvement. This article is designed to help you get the most out of playing your mono LPs in a modern stereo world.

What Exactly Is a Mono Record?

The answer to this question is potentially quite complicated. The difference between mono recordings and mono masterings of recordings needs clarifying, as does the difference between mono records cut before and after the death of the mono format in the late 1960s. For the purpose of this article though we can settle for a simpler definition of a mono record being a record that is intended to produce the same exact audio signal in both the left and right channels of a stereo audio chain. True, without any fuss a listener will hear roughly the same thing coming from both speakers when they play a clean mono record on a stereo audio system (think reissues), but our goal is to hear the exact same thing from both speakers and in the process lower distortion and improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the overall listening experience. This goal becomes especially important when dealing with original pressings made in the 1950s and 1960s that have accumulated a significant amount of wear from usage.

Knowing If a Record Is Mono

Before we get started, let’s be sure that our records are even mono in the first place (by all means, if this is a no-brainer for you, feel free to skip this section). The easiest way to tell if a record is mono is if there is some indicator on either the front or back of the album jacket. For vintage records (we’re still talking ’50s and ’60s), the absence of the word “stereo” will usually suggest that a record is mono. The next easiest way to tell is simply by listening, and the best way to achieve this goal is with headphones. If the music sounds mono (like it’s in the center of the stereo field) but the surface noise sounds stereo (wider in the stereo field), your record is mono. Note that the loudest parts of a mono record are where you will hear the first signs of distortion from wear, and at those moments the music may sound like it’s stereo (though it shouldn’t), so focus on quieter parts of the music. Finally, to state the obvious, if there are instruments or sounds distinctly positioned to either the left or right side of the stereo spread, your record is stereo. In cases where the stereo positioning of instruments is more extreme — common in our era of the ’50s and ’60s — you can also easily identify a stereo record by turning the panning knob on your amplifier all the way left then all the way right and back again. If some instruments sound very present at one turn then very distant or completely absent at another, then your record is stereo.

What’s Wrong with Listening to a Mono Record in Stereo?

If you’ve been listening to mono records in stereo your whole life, there are two significant ways in which your listening experience can be improved by effectively listening in mono on a stereo system. First, surface noise can be reduced and made less noticeable. Many marks on the surface of a vinyl record manifest as out-of-phase noise on the far left and right of the stereo field. When listening to a mono record on a stereo audio system, these pops and ticks are heard in a very different position than the actual music, which lies directly in the center of the stereo field. By listening in mono though, not only does the out-of-phase nature of this noise lead to its reduction in relation to the volume level of the music, much of whatever surface noise remains will be masked by the music in the center of the would-be stereo field.

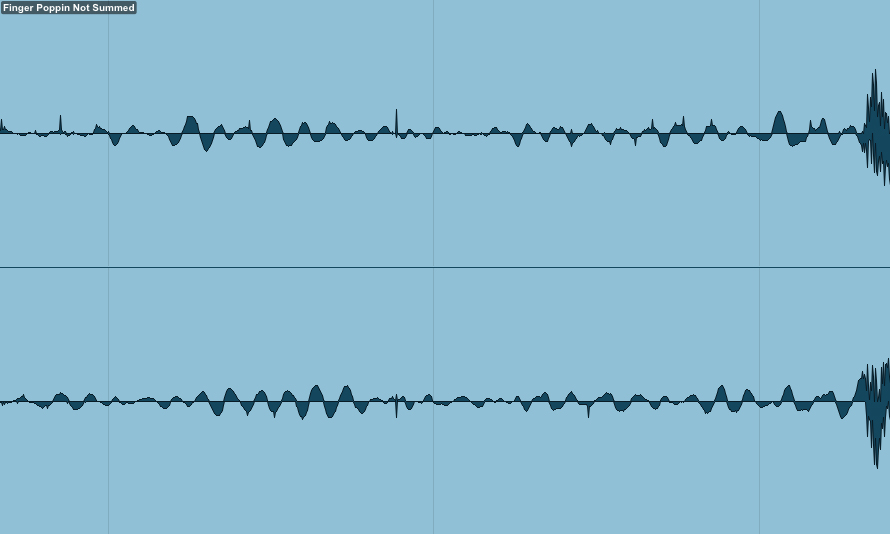

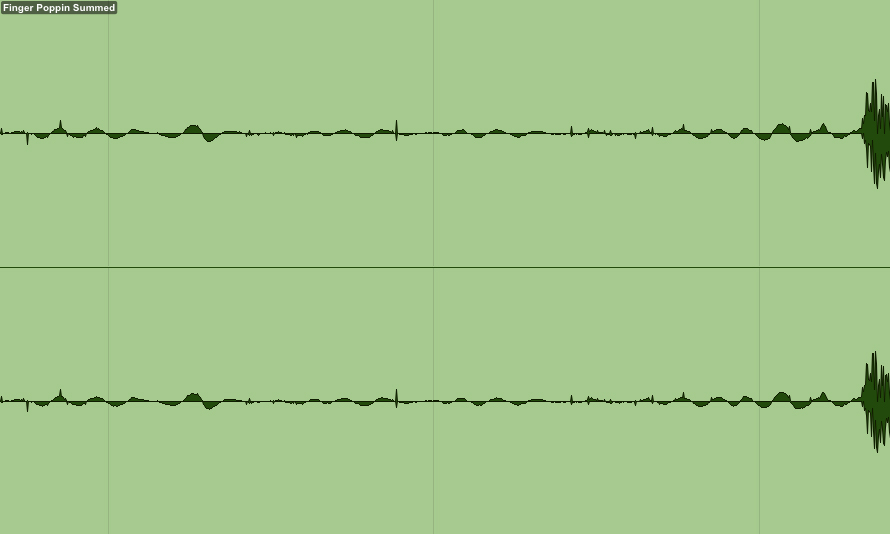

Presented here are two audio clips. The first is of a mono record being played in stereo, the second being the same record played in mono. In the second clip, notice how the surface noise has collapsed to the center of the “stereo field” and is more difficult to discern once the music kicks in:

Horace Silver, “Finger Poppin'” (Original 1959 mono pressing of Finger Poppin’ with the Horace Silver Quintet)

Stereo Playback:

Mono Playback:

Second and similar to surface noise, groove wear on vintage mono records also often manifests as out-of-phase (stereo) noise. This distortion can also be reduced by listening in mono, and the fuzzy, smeared sound that would be heard listening in stereo becomes a tighter, more focused central image. The following audio clips emphasize this type of improvement:

Lou Donaldson, “Avalon” (Original 1962 mono pressing of Gravy Train)

Stereo Playback:

Mono Playback:

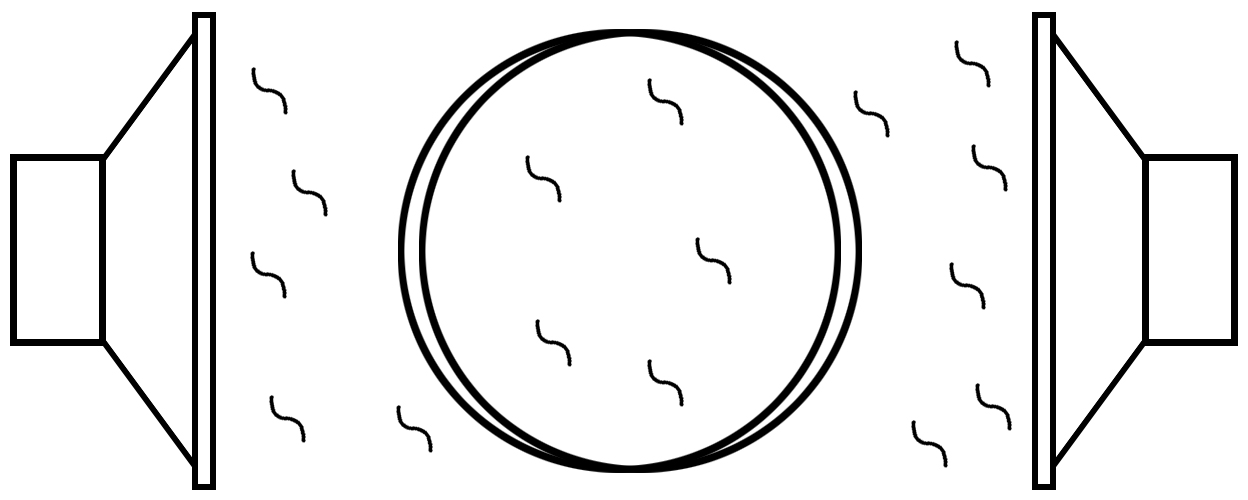

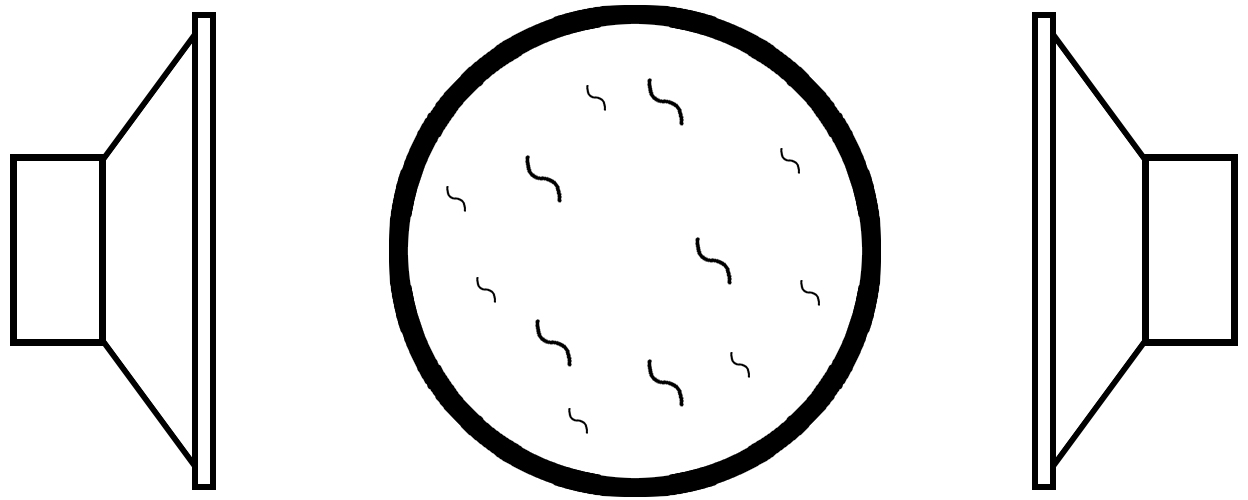

For a visual account of these improvements, the following two diagrams illustrate how listening to mono records in mono can provide an improved listening experience (the circles represent music and the curved lines represent surface noise):

Stereo playback of a mono vinyl LP

Mono playback of a mono vinyl LP

How Do I Play My Mono Records in Mono on a Stereo System?

Now that we’ve identified the ways in which playback of your mono LPs can be improved, how do we achieve this? Everyone has different equipment situations so there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but surely there is a sensible option for everyone.

If you use a turntable with a tonearm that accepts removable headshells, the most obvious hassle-free solution is to acquire a mono cartridge. Luckily, getting a mono cartridge doesn’t mean you need to hunt down a vintage one. Cartridge manufacturers like Ortofon, Grado, Audio-Technica, and Miyajima all currently provide quality mono cartridge solutions that are compatible with modern stereo turntables.* You may need to adjust your counterweight each time you switch, but when you want to play a mono record, simply swap cartridges. (Click here to visit the Deep Groove Mono Cartridge Database.)

A sampling of mono cartridges currently on the market

If you don’t have a tonearm that uses removable headshells, or if you simply don’t want to fuss with swapping the cartridge and adjusting the counterweight every time, there are other options. While a mono cartridge will produce identical signals in both channels of a stereo system (a duplicated “mono signal”, if you will), simply summing the left and right channels of a stereo cartridge can actually produce comparable results (for more information, see the appendix at the end of this article).

One way to do this is with a mono button on an amplifier. Many vintage stereo amplifiers have mono buttons. If you don’t have access to one of these vintage amps, you can also sum with a stereo-mono switch, though these can be hard to find and are usually custom-built (members of the Steve Hoffman Forum can purchase one here). Another summing option is using a “double Y-cable” configuration, which involves placing a pair of RCA adapters in the signal chain, though the obvious drawback of this option is that you need to remove the adapters every time you switch between mono and stereo (the method is outlined here in this Steve Hoffman Music Forum thread).

Will either using a mono cartridge or summing provide more favorable results? Though the answer to this question certainly depends on which cartridges you are using, here we offer up one of these comparisons. The first is the result of playing a vintage mono record with a Grado MC+ mono cartridge and the second is a clip of the same record being played with a Shure M44-7 stereo cartridge and the mono button engaged on an integrated amplifier:

Johnny Coles, “Jano” (Original 1964 mono pressing of Little Johnny C.)

Grado MC+ mono cartridge:

Shure M44-7 stereo cartridge with channels summed:

A final, less popular option is to use a “left channel only” or “right channel only” setting on an amplifier. Unlike a mono setting that sums the channels, these settings will duplicate one of the two stereo channels in both signal paths. While this method typically fails to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the signal, it is preferable in some rare instances. For example, if a record was played many times on a turntable with severe anti-skate problems, one groove wall may be in much better shape than the other, and listening to one channel or the other may prove more desirable than summing.

McIntosh MA6200 integrated amplifier with mono, L-to-L&R, and R-to-L&R settings

Vintage vs. Modern Mono Records & Stylus Size: Is Bigger Always Better?

The only other variable that modern mono lovers need to consider is stylus size. Today’s stereo (and mono) LPs are cut with a groove width optimized for playback with a modern stylus tip measuring approximately 0.7 mils at its longest radius (1 mil equals 0.001 inches or one-thousandth of an inch; in the metric system, 0.7 mils is equivalent to about 18 “microns” or micrometers, where 1 micron equals 0.001 millimeters or one-millionth of a meter). However, vintage mono LPs mastered prior to 1970 were actually cut with the intention of being played back with a larger 1-mil (25-micron) stylus.

For mono LPs mastered after 1970, a 0.7-mil stylus is the only sensible option. Fortunately, this is the spec for virtually all modern cartridges, mono and stereo alike (a few exceptions to this rule are the Ortofon OM cartridge with optional D25M stylus, the Ortofon CG 25, and the Miyajima Zero, all which sport 1-mil styli). As for playback of vintage mono LPs mastered before 1970, while it’s true that these discs were cut to be played with a 1-mil stylus, a 0.7-mil stylus will also fit these grooves. What’s more, there’s an attractive theory that a narrower 0.7-mil profile might avoid areas of wear higher up on the groove wall created by repeated plays back when 1 mil was the standard. In a perfect world, collectors would have both options at their disposal and make their choices on a case-by-case basis. But in the event that you must choose one stylus for playback of all mono and stereo LPs from all eras, a 0.7-mil stylus should suit you just fine.

(L to R) Ortofon OM with D25M stylus, Ortofon CG 25, Miyajima Zero

Once more, we have two audio clips to offer up for comparison. The first is a vintage mono LP from 1959 being played with the previously mentioned Ortofon OM cartridge and D25M 1-mil conical stylus, and the second clip is the same record being played with a Shure M44-G cartridge with a 0.7-mil conical stylus (both cartridges are stereo and channels are summed for both clips):

Donald Byrd, “Lover, Come Back to Me” (Original 1959 mono pressing of Off to the Races)

Ortofon OM cartridge with D25M 1-mil stylus:

Shure M44-G cartridge with stock 0.7-mil stylus:

Note that stylus size in and of itself has no bearing on whether a record will play mono or stereo; the inner workings of the cartridge are what ultimately determine this.

Conclusion

Despite stereo’s current reign as the industry’s standard format, mono sound has certain qualities that distinguish it from stereo and make it special. When done right, mono can be a highly enjoyable listening experience. Mono recordings have a simplicity that give them character. Their “punch” is intrinsically tied to the limitations of the format, and the same can be said of the way the elements of a mono mix meld together into one cohesive whole. My hope is that this article has explained how to get the most out of your mono records and has also provided you with a practical, affordable solution in your quest to obtain the finest mono vinyl playback possible.

* Advanced collectors will appreciate a note regarding the difference between single-coil and dual-coil mono cartridge design. In theory, a single-coil design will provide an even higher signal-to-noise ratio than a dual-coil design. Known single-coil models include the Ortofon CG 25, Miyajima Zero, and Denon DL-102. Additionally, mono carts with no vertical compliance (the CG 25 and Zero) may also produce superior results, though newcomers should be aware that the lower compliance of these cartridges requires a special high-mass tonearm to achieve the appropriate resonant frequency for the system.

Appendix

“Stereo information” in a stereo record is information that is not equally present in the left and right channels of a stereo signal, and it is determined by the unique vertical modulations cut into each groove wall. “Mono (centered) information” is equally present in both channels and is determined by horizontal modulations in the groove only. Since surface marks on a record generate both horizontal and vertical motions of a stylus, playing a mono record with a stereo cartridge will not only reproduce noise related to the vertical motions of the stylus, that noise will usually be more noticeable because it will be in a very different position than the music in the stereo field. Using a modern mono cartridge will certainly cure this ailment, but summing a stereo signal from a stereo cartridge will produce noticeable improvements as well. The reason for this is because much vertical noise in a record’s groove is “out-of-phase”, meaning that the voltages produced by the cartridge’s left and right channels are to some extent polar opposites of each other, so when they are summed together, not only is the volume of this (stereo) noise reduced, the relative volume of the mono information i.e. the music is slightly boosted as well.

To illustrate this, the screenshots below show various waveforms in a digital audio workstation. The first shows the left and right channels of a mono record being played in stereo, while the second shows the same record played with the left and right channels summed using the mono button on an amplifier (both clips use the same stereo cartridge):

Lead-in groove of a mono record being played in stereo

Lead-in groove of the same mono record being played with channels summed to mono

Additional Resources:

(1) Deep Groove Mono Cartridge Database: Deep Groove Mono’s own database of mono cartridges currently on the market

(2) “Ortofon True Mono Cartridges”: Fantastic article on the Ortofon website discussing the history of monophonic playback

(3) “RCA Victor Announces Living Stereo”: 1958 short film explaining the science of stereo records (YouTube link)

(4) Stereo Cutting Head GIFs: Awesome GIFs explaining the science of stereo cutting heads, courtesy of VinylRecorder.com

Vinyl Spotlight: The Horace Silver Quintet, The Tokyo Blues (Blue Note 4110) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1962 mono pressing

- “NEW YORK USA” on both labels

- Plastylite “P” etched and “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

- “43 West 61st St., New York 23” address on jacket without “Printed in U.S.A.”

Personnel:

- Blue Mitchell, trumpet

- Junior Cook, tenor saxophone

- Horace Silver, piano

- Gene Taylor, bass

- John Harris, Jr., drums

Recorded July 13-14, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released November 1962

| 1 | Too Much Sake | |

| 2 | Sayonara Blues | |

| 3 | The Tokyo Blues | |

| 4 | Cherry Blossom | |

| 5 | Ah! So |

Selection: “Sayonara Blues” (Silver)

This record is one of the finest examples of engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s original mono mastering work in my entire collection. Granted, I only own a handful of these, but I’ve had dozens more pass through my hands over the years and this is definitely one of the good ones. What makes it one of the best? Condition. Since so many original Blue Notes seem to have suffered groove damage at the hands of primitive playback equipment, I have found that the key ingredient in a stellar-sounding original is the extent to which past usage has left its mark on the record. Not only does this record look amazing 55 years after it would have been taken home from the store, the sound is still fresh and vivid — the way you might expect it to have sounded back in 1962.

It’s possible that bandleader Horace Silver’s choice of a Far Eastern theme influenced drummer John Harris Jr.’s choice of a more minimal, sparse style of playing throughout, which gives each instrument plenty of room to breathe and cut through. (Less percussive energy also provides less of a challenge when getting the music onto tape and into the grooves of the wax.) The standout moment here is Silver’s four-and-a-half-minute romp on the keys in “Sayonara Blues”, a solo with trance-like qualities reinforced by a two-chord, left-hand mantra.

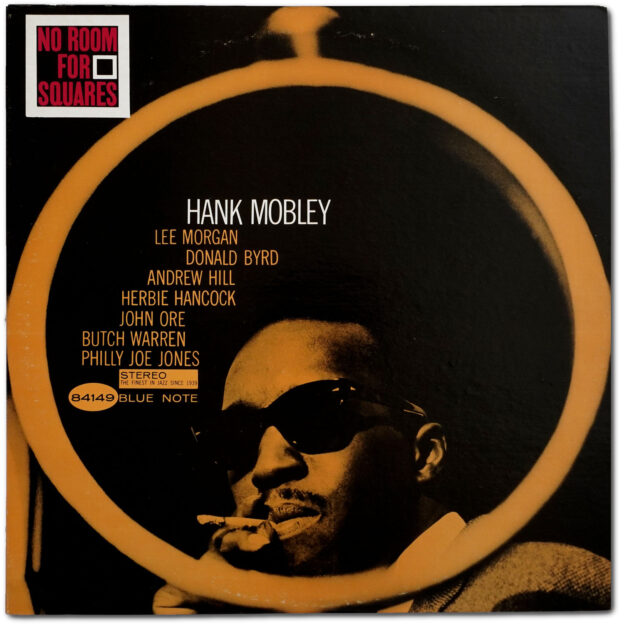

Vinyl Spotlight: Hank Mobley, No Room for Squares (Blue Note 84149) UA RVG Stereo Pressing

- United Artists stereo reissue circa 1975-1978

- “VAN GELDER” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

All but “Up a Step”, “Old World, New Imports”:

- Lee Morgan, trumpet

- Hank Mobley, tenor saxophone

- Andrew Hill, piano

- John Ore, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

“Up a Step”, “Old World, New Imports” only:

- Donald Byrd, trumpet

- Hank Mobley, tenor saxophone

- Herbie Hancock, piano

- Butch Warren, bass

- Philly Joe Jones, drums

“Up a Step”, “Old World, New Imports” recorded March 7, 1963

All other selections recorded October 2, 1963

All selections recorded at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Originally released May 1964

| 1 | Three Way Split | |

| 2 | Carolyn | |

| 3 | Up a Step | |

| 4 | No Room for Squares | |

| 5 | Me ‘n You | |

| 6 | Old World, New Imports |

Selection:

“Three Way Split” (Mobley) [Stereo]

“Three Way Split” (Mobley) [Summed Mono]

So far on Deep Groove Mono, we’ve covered original pressings, Liberty pressings and early ’70s United Artists pressings of classic albums released by the beloved Blue Note label. This ’70s copy of Hank Mobley’s No Room for Squares with the all-blue label and the white (sometimes black) lowercase “b” logo is more or less the last phase in vintage US Blue Note pressings. (Prior to the current era of audiophile reissue programs, which gained great momentum in the late ’90s with Classic Records, the ’80s and ’90s saw a series of less popular, less acclaimed reissue programs eclipsed by the advent and subsequent reign of the compact disc.) This reissue program also constitutes the last time the original mastering work of engineer Rudy Van Gelder would be used to press reissues of classic Blue Note albums.

As is the case with the earlier mono UA reissues of the early ’70s with the classic blue-and-white label scheme, these all blue-label reissues seem hit or miss. This is at least in part due to the fact that Van Gelder’s metal work was being employed beyond the point where it could produce records of the exceptional quality originals and earlier reissues are known for. Several Blue Note albums I have encountered with all-blue-labels and Van Gelder mastering have been duds, but No Room for Squares is not one of them.

This is one of my favorite Hank Mobley albums. Recorded in 1963, it is far removed from the string of 1500-series albums Mobley recorded for Blue Note in the late fifties, all of which are very rare and in-demand in their original incarnations. Nonetheless, Mobley puts together a solid, consistent program here, best demonstrated by a pair of the leader’s own compositions (the title track and “Three Way Split”) and the ballad “Carolyn”, an original work of session trumpeter Lee Morgan. Then-veteran of the bop scene, drummer Philly Joe Jones, provides a driving and exciting performance on the skins as well.

Though this is a stereo copy, it is tempting to hit the ‘mono’ button on my amplifier in order gain a sense of what an original mono pressing might sound like. The reason we can be fairly certain that this type of summing can produce comparable results is because of what we know about the way Rudy Van Gelder recorded, mixed, and mastered these albums for both mono and stereo. Though the clarity and separation offered by the stereo spread is a treat in its own right, summing to mono provides a glue to the mix that the stereo presentation is incapable of, especially when it comes to the harmonies of the horns.

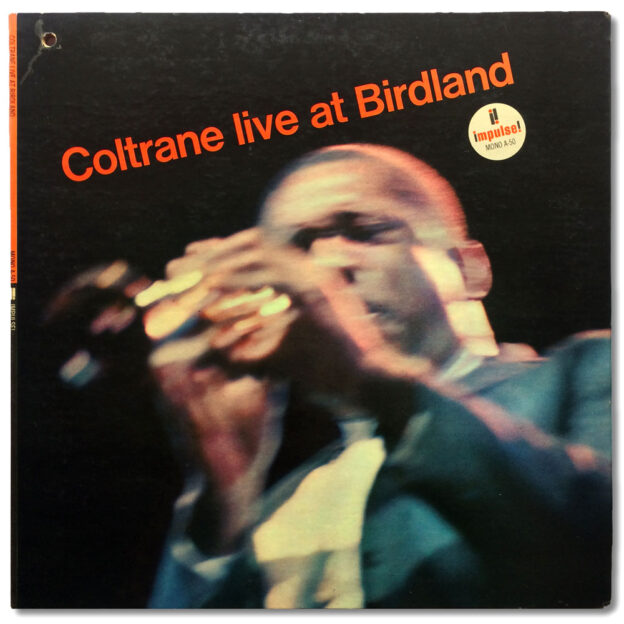

Vinyl Spotlight: John Coltrane, Coltrane Live at Birdland (Impulse 50) Original Mono Pressing

- Original 1964 mono pressing

- “ABC-Paramount” on labels

- “VAN GELDER” in dead wax

Personnel:

- John Coltrane, tenor and soprano saxophone

- McCoy Tyner, piano

- Jimmy Garrison, bass

- Elvin Jones, drums

All but “Alabama”, “Your Lady” recorded October 8, 1963 at Birdland, New York, New York

“Alabama”, “Your Lady” recorded November 18, 1963 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Originally released April 1964

Selection: “Afro Blue” (Coltrane)

Generally speaking, I don’t know the Impulse catalog very well, and accordingly I have a harder time keeping track of the ‘first-first pressing’ melee associated with the label. Thus I’m not really sure if this is a ‘first-first pressing’ or just a ‘first pressing’, but it has the Van Gelder stamp of approval and, more importantly, it plays through without the hideous artifacts of groove wear so I’m a happy camper. This copy had a lot of light scuffs when I first looked at it, which is probably what kept the price down, but by the time I got it home and gave it a listen I was happy to find that this was a rare case of a record ‘playing better than it looked’. I am so inspired by the intensity with which John Coltrane played the soprano saxophone during this time period, and “Afro Blue” is a fine example of that passion and vigor.