|

(Ed. Note: I originally intended to do a formal interview with Joe and Kevin, but as the day progressed and the friendly vibe between us grew, I became less and less interested in the idea of shifting gears into being “on the record”. So I kept it casual. As a result, this article is a narrative and not in a traditional interview format.)

Back in 2012, when I first caught the jazz record collecting bug, I quickly took a strong interest in recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who recorded for numerous classic jazz labels including Blue Note Records. I had a background as an amateur audio engineer so I was also interested in his methods. On one occasion, I reached out to mastering engineer Kevin Gray, who had been working with Rudy’s original master tapes for several years in conjunction with various jazz reissue labels including Music Matters.

Kevin was very polite and helpful, so a few years later when I published an article on groove wear, I thought it would be a good idea to ask Kevin to proofread it before it was published. After he read it, he wanted to talk to me over the phone, so that was the first time we spoke.

On a few occasions I would ask him questions about my research so we stayed in touch. Then last November when I launched RVG Legacy, a website dedicated to preserving the legacy of Rudy Van Gelder, I let him know about it. It must have flown under his radar until this summer when he emailed me excited about what I had put together. A couple weeks later he emailed me again, saying he had been talking to Blue Note reissue producer Joe Harley about my Rudy site, and they decided to invite me to a Blue Note remastering session at Kevin’s mastering studio, Cohearent Audio in Los Angeles.

I was beaming with excitement. For the first time I would get to hear Rudy Van Gelder’s original master tapes in person, someone whose methods and sound I had been carefully studying for the past ten years. So I booked a flight and waited patiently for the day to come where I packed my bags and headed for the West Coast.

|

| Rudy Van Gelder in his Englewood Cliffs studio in 1962 (Photo credit: Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images LLC) |

An Unexpected Listening Exercise (and Outcome)

The first morning I was in SoCal, my co-pilot, Tarik, and myself began the 90-minute drive west from San Bernardino at 8 A.M., headed for Cohearent. Upon pulling up to the address, Tarik and I were met with the unassuming façade of a small, single-floor, seafoam green house. We had been instructed to go through the gate to the building on the back of the property.

|

| World-class mastering incognito: View of the Cohearent Audio property from the street |

Once inside, it wasn’t long before Kevin hit “play” on one of his Studer reel-to-reel tape recorders. While we waited for Joe to arrive, the sound of music began flowing from Kevin’s massive custom-built speakers at the front of the room, each of which consists of two subwoofers with sealed enclosures, two woofers, one midrange driver and one tweeter.

Before I tell you what happened next, I think it’s only fair that I preface it with a comment about what kind of listener I am. I am a very honest listener. I don’t pull any punches. For example, if it costs ten times as much and sounds the same to me, I’m going to be honest about that.

When Kevin played that first tape, it literally made me tear up. (I wish I could tell you what it was. All I can say is that it was a recording made by a well-known yet underrated West Coast jazz recording engineer in 1958.) I had a strong emotional response that was completely unexpected. If I had to describe what it was that made it sound so special, I’d guess that it was a combination of lifelike dynamics and a very natural stereo soundstage. I know this may sound cliché, but in a word, it was haunting.

Keep in mind that my experience cannot be attributed to the tape alone. Of course, Kevin’s playback system and room also played an important role. After talking to Kevin a little about his background, it became clear that he is a master of electrical engineering and acoustics, and the evidence is in the spectacular playback achieved in his studio, which he designed and built himself, bass traps, electrical wiring and all.

The second thing Kevin played for us was a tape of a Rudy Van Gelder recording dating back to 1961. Time for another preface…

I adore Rudy Van Gelder. His story of creative and entrepreneurial independence has inspired the way I work and live for many years now, going all the way back to 2004 when I first read the book Temples of Sound. Being someone who has always firmly believed that audio recording is an artistic medium that should not necessarily be used in a way that attempts to imitate life as closely and objectively as possible, I have always appreciated the unique character of his recordings. I have stuck up for Rudy in internet chat rooms when he was getting trashed by audiophiles claiming to be “in the know” about other great jazz engineers like Roy DuNann and Fred Plaut.

That said, when the Rudy tape came on, I did not feel as “wowed”. And I think the most important factor here was my feelings — how the sound and the music made me feel. In comparison, Rudy’s tape sounded a little “hyped up”. The top end was much more present, and the sound was less relaxed. What this ultimately amounted to, I feel, is that where the first recording sounded chillingly like the musicians were in the room with us (I have listened to expensive home audio systems before and never got this feeling), the Rudy recording sounded like a recording — an outstanding, gorgeous recording, but nonetheless a recording. And maybe that makes sense since Rudy never claimed to try to make his records sound “as realistic as possible”.

It’s also possible that I came to the studio that day with my own prejudice, that I subconsciously was setting a bar in my mind for “realism in playback”. Most jazz collectors and audiophiles will agree that the greatest classic jazz recordings are the ones that sound the most realistic. I also feel it’s important to keep in mind that Joe Harley has on more than one occasion explained that his goal as a remastering engineer is to make his reissues sound as close as possible to the experience of being in the room with the musicians themselves. In light of this, perhaps it wasn’t unreasonable for me to have those expectations.

Now of course, this was not an apples-to-apples comparison, far from it. In fact, there are too many uncontrolled variables to list. My reaction might have also been different if the Rudy tape was played first. The Rudy tape was of a classic, breathtaking recording of his that I have long admired. It’s just that hearing that tape didn’t necessarily feel a whole lot different than my experiences listening to the same album at home (Kevin’s amazing playback system aside). I should also mention that I had never heard the first recording by “Engineer X”, so it’s possible that this element of surprise also played a part in that recording’s “wow” factor.

While the Rudy recording was playing, Joe came busting through the door, reference vinyl LPs in hand. He gave me a COVID era-appropriate fist bump. Kevin then pulled a large blue plastic bin from a closet and shoved it across the floor in Joe’s direction. Joe then opened it up to reveal some of the most precious treasures in all the world of music: about a dozen original master tapes dating back to the 1950s and 1960s, all jazz recordings and almost all made with loving care by Rudy Van Gelder.

|

| Joe Harley reaching into the magic blue bin for the day’s tapes |

The Morning Session

Joe then handed a tape box to Kevin and Kevin started loading it on to a different Studer deck that he uses for most of his mastering work. The tape was of a Blue Note album originally recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack home studio in 1957 (I was asked to not name specific recordings). Before I went to L.A., Joe told me were going to work on this album in the morning and another in the afternoon. Knowing the morning album’s history, I was privately hoping I would get to hear both the original mono and stereo tapes in person, and was pleased that both tapes were in the blue bin.

Joe gave Kevin the mono tape first, and before I knew it we had launched into a comparison of the mono and stereo tapes to decide which would be used for the Tone Poet reissue (slated for next year). Tarik and I sat in the back of the room and quietly watched Joe and Kevin work their magic. The tape was wound “tails out”, a common reel-to-reel tape storage practice intended to avoid audible “print-through”. As such, Kevin rewound past the album’s ending solo piano ballad to a piece featuring the entire band. (Interestingly, the mono master was on a single reel but the stereo was on two reels.)

Joe shifted his chair center to better judge what he was hearing. He and Kevin partook in some inaudible chatter, then Joe got up to put the Japanese stereo reissue he had brought with him on Kevin’s lathe, which doubles as a turntable complete with V-15 playback cartridge and tonearm to the side. The intention was to quickly switch between the mono and stereo presentation, something that couldn’t be done with just one tape machine. Once the record was spinning, there was more inaudible chatter between them, but I did manage to make out that Joe seemed to be favoring the stereo presentation.

|

| Critical listening time with Kevin Gray (left), Joe Harley (center), and my copilot, Tarik Townsend (right) |

Kevin began quickly switching reels from mono to stereo when the song was over. Once he had the stereo reel cued up to the beginning of the first side and playing, it wasn’t long before Joe began singing its praises. He was clearly moving toward using the stereo tape for the reissue, and seemed to have been from the very start.

From where I was sitting, the mono tape sounded pretty darn good. A little bright, but the balance between the musicians was solid. I didn’t know what to make of the comparison between the mono tape and the stereo LP, but once they put the stereo tape on, my first thoughts were, ‘That’s pretty bright,’ and, ‘It sounds like nothing is on the right.’ In all fairness, I was sitting back further than them and I wasn’t close to the sweet spot. Still, the stereo presentation clearly offered a greater sense of width in space.

Prior to this, I noticed that Joe had been reading a 6-by-6 cardboard card that was inside the mono tape box, and a few minutes after the stereo tape had begun playing, Joe explained that someone had left a note about tape damage on the mono tape in a spot we hadn’t heard. That was all it took for him to confirm with Kevin that they were going to use the stereo tape for the Tone Poet reissue. Several minutes later, by the end of the first side, EQ moves and other adjustments contributed to what I felt was a smoother top end and a more even stereo spread (at one point Joe explained that the vinyl manufacturing process would naturally relax the top end a little more as well).

|

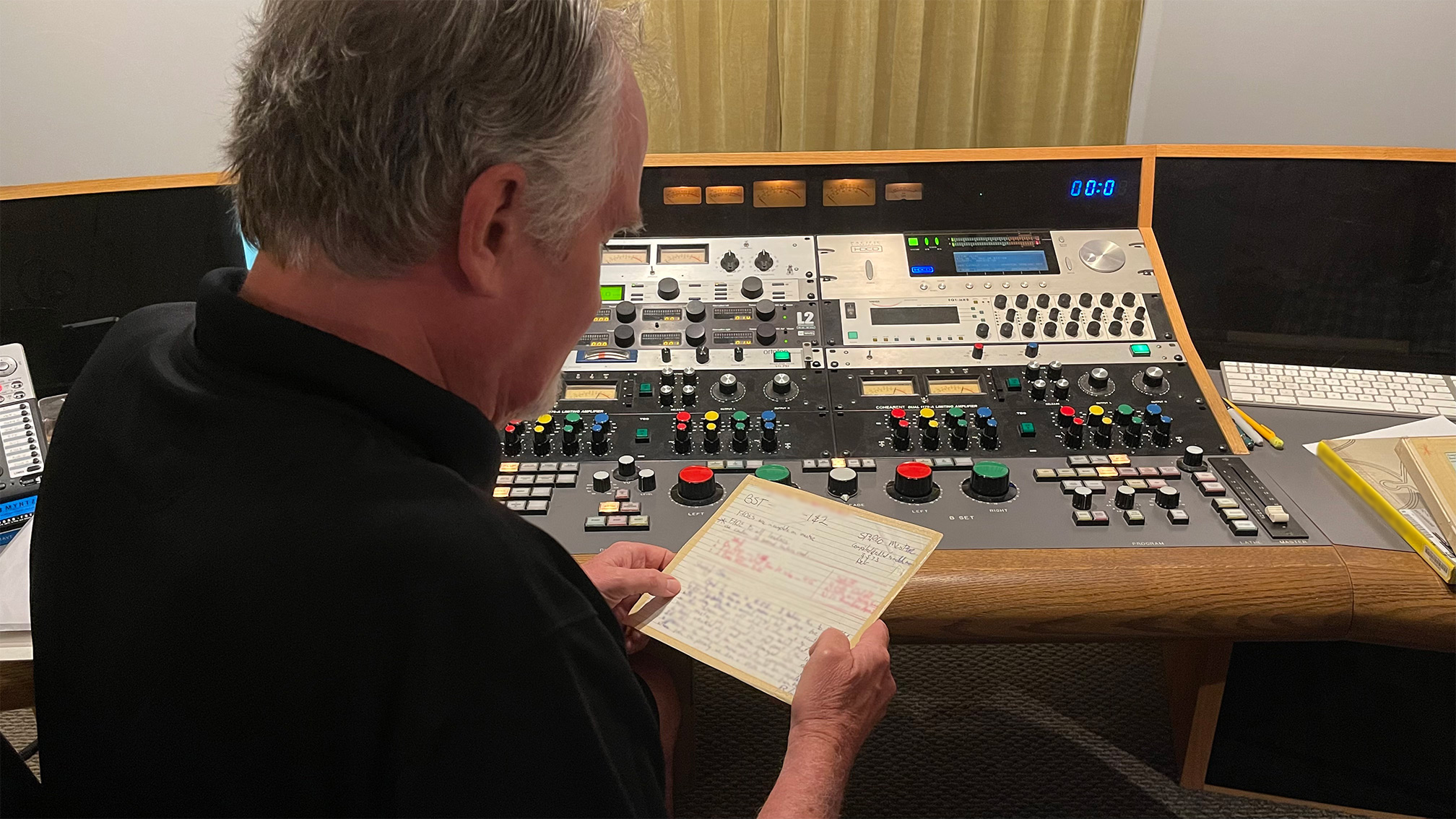

| Joe peering at notes left by a previous mastering engineer |

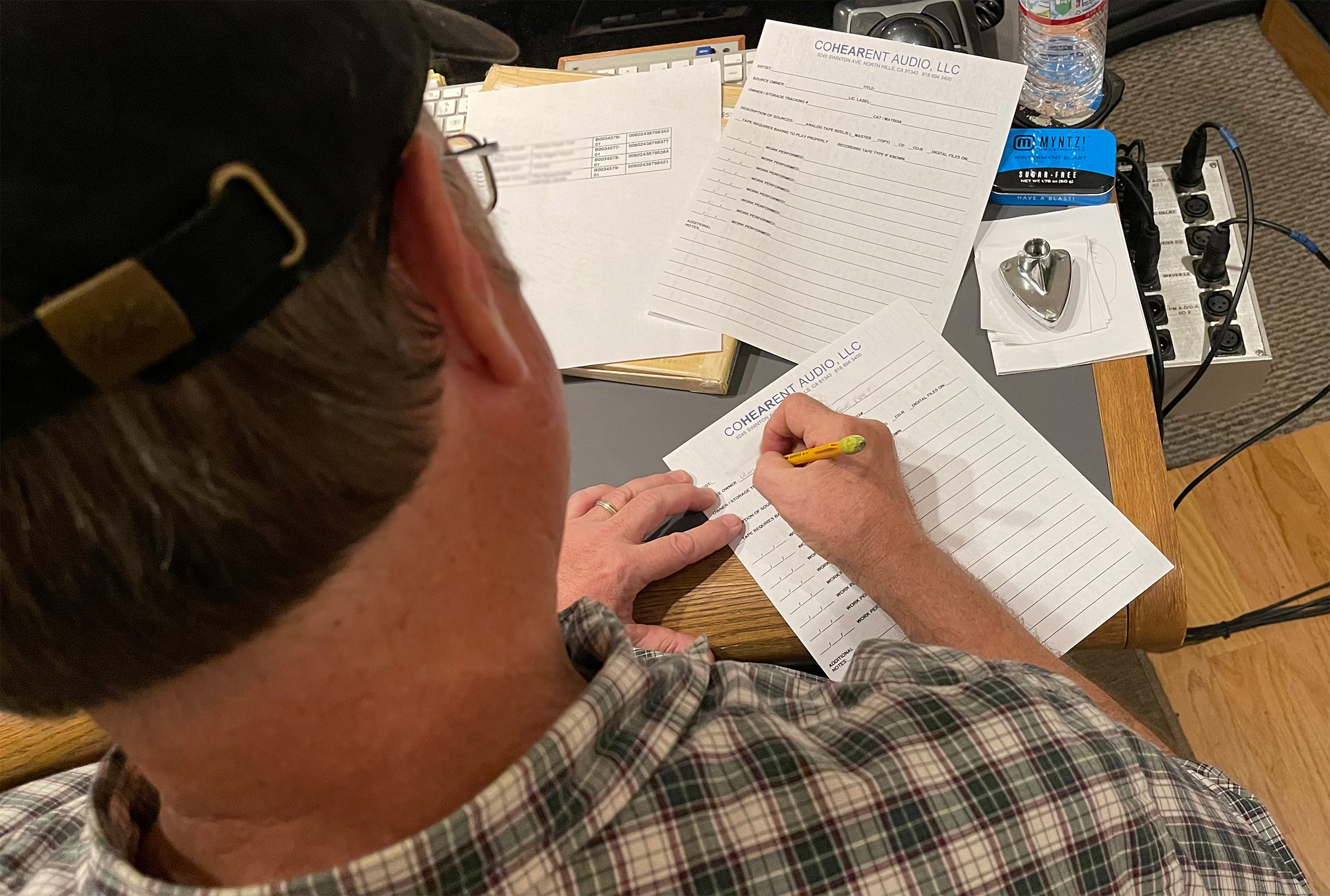

As we listened through the entire album on the stereo reels, we all chatted while Joe and Kevin multitasked. Joe would occasionally make a quick comment to Kevin about the volume levels between tracks, and Kevin kept busy taking his official session notes, which he explained serve the primary purpose of making it easier to go back and redo the mastering should any problems pop up between the lathe and the presses.

|

| Kevin taking session notes |

It was also at this time that I boldly asked Joe and Kevin if I might be able to move my chair up to the center of the console so I could sit at the sweet spot. They happily obliged, and when I did — again, I don’t like to overdramatize these things — it felt like I had stepped in to the Hackensack living room after standing outside the doorway. All the musicians quickly snapped into position, creating a lush stereo image with swirls of airy reverberation bouncing around (sitting between big speakers like Kevin’s, you can’t help but feel wrapped in sound). I had a stronger sense of the soundstage, and the music’s dynamics also became more apparent. Still a little bright to my taste but nonetheless a significant difference compared to when I was sitting further back.

|

| Listening in the sweet spot (Kevin’s monitors are between the curtains, the white strips are the grills) |

From there, Kevin readied his Neumann lathe to create the lacquer disk masters that would be sent to Record Technology Incorporated, or RTI, for plating and pressing immediately after the session (Kevin hurried off to Fed Ex as soon as we were through with the afternoon session). Joe gave Kevin a gentle reminder: “Did you say you were gonna swap out the cutting stylus?” Before pressing play, Kevin also readied his digital recorder in order to make a high-resolution digital transfer for Blue Note as well. Once the tape was rolling and the lathe was cutting, Kevin was free to talk, but between takes he excused himself so he could implement small fadeouts at the end of each song (there was a note inside the tape box to do so).

|

| Kevin getting ready to do a manual fadeout |

The Afternoon Session

After we went to lunch, we came back for the afternoon session. The album we would be working with was recorded in 1965 at Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. It featured a bigger band and presented a marked difference in sonics. The routine was more or less similar to the morning session, though there was only a stereo tape to be used this time, so no fussing over mono and stereo. After Gray and Harley got a good sonic balance, I once again asked to pull my chair up. Though I had never heard this album before, I was familiar with other work the trumpeter and drummer did for Blue Note from that time period. Here, I heard a more significant difference compared to what I was used to hearing. The sweet spot revealed a very nice balance between all the instruments, and the drummer sounded especially dynamic and realistic compared to other records I had heard him on.

Kevin’s system also seemed to help make the musicians sound less separate than what I was used to. One of my pet peeves about Rudy Van Gelder’s standard stereo spread in the 1960s is that the left channel often feels empty when the saxophonist is soloing on the right alongside the drummer. On Kevin’s system though, the microphone bleed and overall ambience of Van Gelder Studio was more consistently apparent, even in the trumpeter’s absence, which led to both greater cohesiveness within Rudy Van Gelder’s “primitive” stereo mix as well as a stronger sense of spatial balance throughout the performance.

I often listen to music on headphones (while I’m doing other things), where stereo separation is typically exaggerated. But regardless of whether the master tape, Kevin’s rig, or both played a significant role in creating that beautiful spatial balance I heard, I walked away from Cohearent Audio that day having learned a valuable lesson: I have done very little focused listening on good speakers in the sweet spot over the years, and above all I think my experience served as a welcome reminder of how rewarding that type of listening can be.

Once our work had been done, we all began saying our goodbyes. Moments later, just as Joe was opening the door to leave the studio, he paused as if he had forgotten something. Quickly turning to me, in a quiet voice he asked, “So are you going to change the name of your site to Deep Groove Stereo now?”

|

| (L to R) Joe, me, and Kevin |