In my time collecting vintage jazz LPs I have always been curious about jazz from the bebop era, which for the most part was originally released on 78 R.P.M. shellac disks. Listening to digital reissues of music from artists who thrived in the 1940s like Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Lester Young was educational, but it still felt like it left something to be desired. Not only did that feeling accompany me when listening to vintage twelve-inch LP compilations of this material, I always felt that if I’m going to go back that far to get closer to the original listening experience, I might as well go all the way to the 78s — assuming I could find them.

But the prospect of studying and acquiring different, older equipment always loomed overhead, and as a result I hesitated to jump into the 78 game. Finally last year I decided to start simple, purchasing a Califone portable player and an original 1948 pressing of Thelonious Monk’s “Evonce” backed with “Off Minor”. The listening experience did not disappoint and my appetite was whet for more.

Months went by and I hadn’t given the medium much thought. I blindly bought a few 78s cheap at a record fair that were recommended by of one of the dealers, but they didn’t quite match up with my taste. I bought another Monk 78 online but returned it for groove wear issues. But then a couple months ago, frustrated with the trendiness and high cost of collecting vintage jazz LPs, I got inspired to purchase a handful of jazz 78s. For the most part this batch of shellac disks sounded great but the Califone was having some trouble tracking a couple of them. Noticing that the grooves of these records were extremely clean led me to hypothesize that the Califone may have had some unique troubles tracking 78s that were either cut hot or cut with a lot of bass.

Upgrading to an Actual Turntable

The overall experience with these new 78s and the Califone was nonetheless positive, which motivated me to investigate other playback options. I soon learned that idler wheel German-made Dual turntables from the 1960s have a good rapport with 78 collectors. So I started searching and soon settled on a model 1218 for sale on eBay.

When I got the table I was virtually clueless as to how it worked and needed to consult an online manual. The auto-play functionality was a bit baffling, as was the proprietary tonearm counterweight mechanism and headshell. After testing it out, it became clear that the seller had cleverly sidestepped any description of playback issues present: “It powers on and the platter turns fine. It works but I am selling as-is due to its age.” That was all quite true, but there were a couple glaring issues: 1. The turntable would not stop, and 2. The auto-return mechanism was malfunctioning.

Through all this, I was able to mount a cartridge and give a few records a spin. I was impressed by what I heard and frankly a little surprised. The speed was extremely stable and the sound was bold and clear. This gave me hope, so I found a seller on eBay who said they service Duals and I reached out to ask him about servicing mine. He said he doesn’t like to have tables shipped to him, so believe it or not he then proceeded via text and phone to guide me through all the necessary modifications my deck needed. Over the years I’ve gotten decent at making mild adjustments, but I wasn’t used to making repairs like this. After a couple hours though, when everything was done and my table was running smooth, I was quite proud of what I had accomplished with the guidance of my new friend.

Finding a Cartridge-Stylus Combo

Without overthinking it I chose to start with a Grado 78C cartridge, which I chose mainly for its ability to track at a higher force of five grams. (I have never shied away from tracking force. Not only have I found that more force helps alleviate surface noise, I have always been skeptical of the theory that more liberal settings will ruin records.) When I gave the Grado a test run, the sound kind of blew me away, and no tracking issues like I had with the Califone. But after several listens, it eventually became apparent that there was some ground hum in the system, hum that wasn’t present when I was testing playback with a Shure M44-7. After doing some research, I learned that Grado cartridges are unshielded, which causes problems with some turntable pairings.

At this point my 78 cartridge knowledge was still limited, and the next attractive option was the Audio-Technica VM670SP, which also tracked at five grams. But there was something underwhelming about it. It was kind of ugly and clunky-looking and rode extremely close to the record surface. My disapproval may not have been all that much about what I was actually hearing, but I had audiophile friends who I knew would back me in making cosmetics factor into my equipment choices. So I pushed on looking for something more ideal.

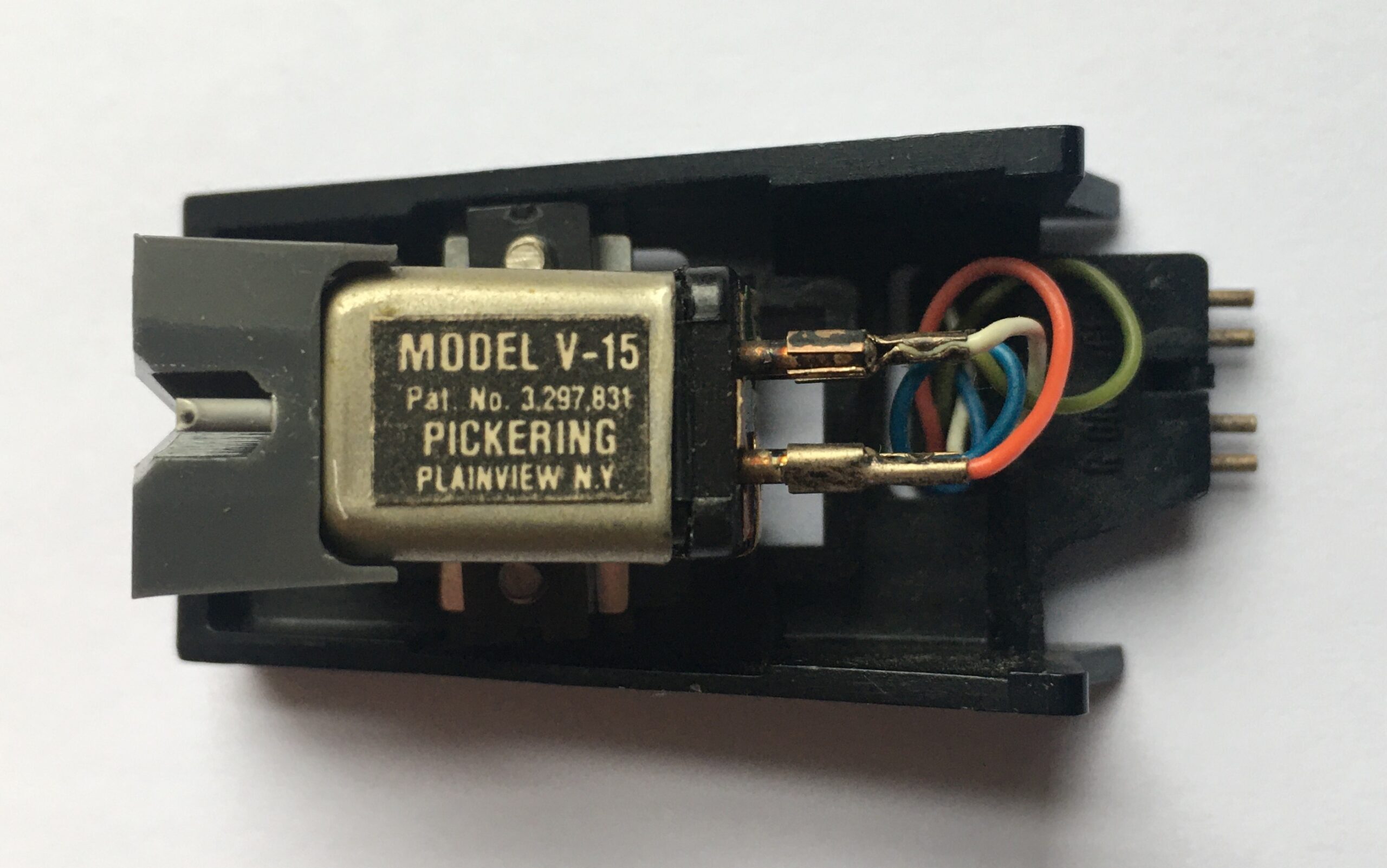

It was then that I got talking to a new vinyl mastering engineer friend, Bill Pauluh, who is an adamant 78 collector. He spoke highly of the Pickering V-15 cartridge and all of its seemingly infinite incarnations. So I found a couple vintage V-15 bodies and a variety of styli: 3.0-mil and 2.7-mil for 78s and 0.7-mil for microgroove LPs. Some were original equipment manufactured (O.E.M.), others were generic “repros” made by Pfanstiehl.

|

| The majestic underbelly of the Pickering V-15 phono cartridge in all its glory |

Shootouts

First I compared the bodies of an original Pickering V-15 cartridge with a later V-15/AME-1 (I have been told that all V-15 model number variations are identical to the original mechanically). Using the same stylus for playback, there was no difference detected. From there I compared 78 playback with the OEM Pickering D1527 2.7-mil stylus and the repro Pfanstiehl 4604-D3 3.0-mil, both sporting conical tips and both tracking at five grams.

Three key differences arose. First, the Pfanstiehl had a slightly brighter top-end — not necessarily an advantage considering that the high-frequency response of most 78s is fairly limited. Second, at certain moments the 2.7-mil Pickering handled surface noise better, yet at other moments — on the same record — the 3.0-mil Pfanstiehl did! These differences were subtle though and took some serious critical listening to detect.

|

| Pickering V-15 in action with original D1527 stylus |

Finally and most significantly, for a few of my 78s there was a sort of swooshing noise with the wider Pfanstiehl. With the narrower Pickering, I was kind of shocked that the noise was completely absent. In the past when I have compared 0.7-mil and 1.0-mil styli with microgroove LPs I never heard this type of dramatic difference. Moving forward, I wonder if the 2.7-mil Pickering will always outperform the 3.0-mil Pfanstiehl in this way; for all I know it will be the opposite sometimes. So while I have found myself going to the Pickering regularly, I’ve decided to keep the Pfanstiehl in the mix.

Playback with Pfanstiehl 4604-D3 Stylus:

Playback with Pickering D1527 Stylus:

Phono Equalization

Through volunteering at engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s studio I became acquainted with his playback equipment, which included a very cool phono preamp that I had never seen before. Introduced in 1983, Conductart’s OWL 1 was designed for playing mono 78s and early mono LPs on modern stereo equipment. By default the OWL sums the input from a stereo turntable to mono, and from there the user has oodles of options for how to equalize the signal.

|

| Conductart’s OWL 1 phono preamp |

There was no collective standard for phono equalization before the RIAA curve was universally adopted around 1954, about five years into the LP era. This meant that each record company’s 78s and early microgroove LPs emphasized different bands of the frequency spectrum, which would result in a variety of different playback equalization curves when being played on a system that lacked the necessary adjustment features (sometimes a “tone control” was included on older equipment as an economical compromise). Accordingly, the OWL 1 gives you a variety of settings that accommodate all the various phono EQ curves from the time before the RIAA standardization.

When I first found out about the OWL 1 I had an interest in both ten-inch and twelve-inch LPs made in the early 1950s so I decided to look for an OWL 1 for myself. After several months of scouring the internet with no luck, an audience member at one of my Rudy Van Gelder talks just happened to mention having one. Instantly I asked, “Can I buy it?”, and I was surprised by how quickly he agreed.

Though there is information out there on which labels used which curves, I have generally been using the same settings. Conductart provides some of this info in their instruction manual but ultimately recommends that the user simply “use their ears” as a guide to setting the controls. Indeed, those favorite settings of mine coupled with some additional lowpass filtering are a substantial diversion from the RIAA curve that would be standard on any modern phono preamp.

Isolation

The one area where I had doubts about the Dual becoming my go-to workstation deck was that of isolation. Although the plinth that it came with was quite clean, I quickly noticed that there were wow and flutter issues if I was walking near the turntable. Surely I have been spoiled by the insane amount of isolation with my Technics 1200s, but I was really happy with the Dual otherwise so I looked for a custom plinth option. I soon found a good-looking, modestly priced option online, which sported a sturdy walnut frame and thick veneer base. Not only did isolation improve with the new plinth, things are looking much better now as well!

Still I felt isolation could be improved, so after yet another several hours of research and conversations with fellow collectors, I decided to purchase two eight-by-sixteen-inch concrete block slabs from Home Depot, place them under each pair of legs, and I decoupled the slabs from the tabletop with eight racquetball halves, four for each slab. While I’d say the isolation of a 1200 is still superior, I’d also say there was improvement in isolation at each of the two phases of this process.

|

| Closeup of cement base with racquetballs used for decoupling |

My Pride and Joy

I have been pleasantly surprised that my new setup rivals the stability and low noise of my 1200, and as a result I have been going to this table for playback of microgroove mono LPs and 45s in addition to 78s. Not only has the unexpectedly high performance of the 1218 allowed me to use a single deck for all my needledrops and critical listening, I have also been feeling a greater sense of pride with it as a consequence of getting it up to spec with my own labor. I also have a soft spot for cost-effective equipment that performs at a high level.

There is also something neat and special about idler wheel design. It may just be that I like the idea of a simplistic mechanism like a pulley spinning a rubber wheel which in turn spins a platter; perhaps I am also a little in awe of just how stable the speed can be under such circumstances. Either way, my new Dual 1218 is giving me joy in a way that my tried-and-true Technics 1200s — tables that have faithfully been with me since 1998 — never have.

And what better way to end my report but with a video needledrop of the new setup in action! Keep an eye out for my new “Shellac Spotlight” column here on the blog!