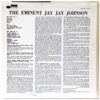

- Liberty mono pressing circa 1966-1970

- RVG etched in dead wax

Personnel:

Side 1:

- Clifford Brown, trumpet

- J.J. Johnson, trombone

- Jimmy Heath, tenor & baritone saxophone

- John Lewis, piano

- Percy Heath, bass

- Kenny Clarke, drums

Side 2:

- Jay Jay Johnson, trombone

- Wynton Kelly, piano

- Charles Mingus, bass

- Kenny Clarke, drums

- Sabu Martinez, congas

Side 1 recorded June 22, 1953 at WOR Studios, New York City

Side 2 recorded September 24, 1954 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released in 10″ format (BLP 5028/5057) in 1953/1954 (BLP 1505 released January 1956)

As with many of these compilations of earlier Blue Note material, there are several different configurations of musicians on each track of this album. But, unlike many of those compilations of 10” and 78 RPM material, this collection of sides contains some of the finest musicians in early bebop. Led by arguably the greatest trombonist in modern jazz, J.J. Johnson, the lineups play fast and furious on the first side with the talismanic Clifford Brown trading very quick riffs with Johnson and Jimmy Heath on the opening track, “Turnpike”. If the song was named after fast traffic on a New Jersey toll road, it is very appropriate. The three horns pound out a hard-driving, repeating riff to open the song. Per usual, Clifford Brown and Jimmy Heath continue the furious pace as they often do on most of the recordings featuring them at the time.

But what is most impressive about fast-paced bop numbers like “Turnpike” that feature a trombonist or tubist is each player’s ability to keep pace with the other soloists. During a short period of time in junior high school, I chose trombone as my first instrument. In those six months, the only thing I learned on the trombone was that it was extremely difficult to play anything fast. My young muscles struggled to play even quarter notes fluidly. I simply could not move the slide into the different positions fast enough to be in key. Having to do that all while breathing in sync with finger motions is very difficult. Knowing what it’s like to move that slide into the perfect position and then hearing J.J. Johnson fly through a solo, playing notes in rapid fire succession with the ease of a trumpeter or saxophonist impresses me every time I play this LP.

On the next song, the same band plays the standard “Lover Man”. Like many standards, it is a classic that has seen very creative interpretation by several musicians. But what sets this reading apart is the bottom end sound of Johnson’s trombone. The other trombonist that I (and frankly, most other collectors) revere most is Curtis Fuller. For me, Fuller always has a somber tone to his trombone sound even in songs such as the classic “Blue Train”, which is a very uptempo song. But Johnson’s tone, though low like Fuller’s, has a very swinging yet casual kind of sound. It seems to dare the audience to sway but not quite dance to the music. Also, Johnson seemed to embrace the wide use of trombones in the new and exciting latin salsa music that was emerging from New York at the time; his music can sometimes have a latin tinge that adds a unique sound to the typical bebop track.

The latin influence is most present on the song that I most enjoy on this LP. Johnson turns the Broadway standard “Old Devil Moon” into a cool, relaxing latin jam. Johnson plays his trombone with a kind of warble, like a guitarist with a wah-wah pedal for a special effect. As he plays the familiar riff, time is kept by one of the most influential drummer of the early days of bebop, Kenny Clarke. As worthy as he is of the praise he receives, for me the most exciting percussionist of the whole compilation is the conguero, Sabu Martinez. I’ve always been a fan of the conga on classic jazz sessions, whether it’s Ray Barretto on such influential recordings as Blues Walk, Manteca, and Midnight Blue, or Martinez, who is very lively on this LP. It is a rare treat to hear Sabu (who had a short life and career due to drug abuse), and he is the perfect fit to a latinized song such as this one.

Strangely enough, Charles Mingus, the biggest name on the session and one of the greatest composers, bassists, and personalities in the history of music, fails to make any kind of impression on me here. Mingus always seemed, to me, to enjoy playing and writing his own material most. Perhaps he felt restrained by playing music composed by others, and in this case maybe he had grown tired of exploring these standards. It is also documented that Mingus did not like the way that Blue Note’s house engineer, Rudy Van Gelder, recorded his sound. I notice the bass of Percy Heath far more on the record than I do Mingus.

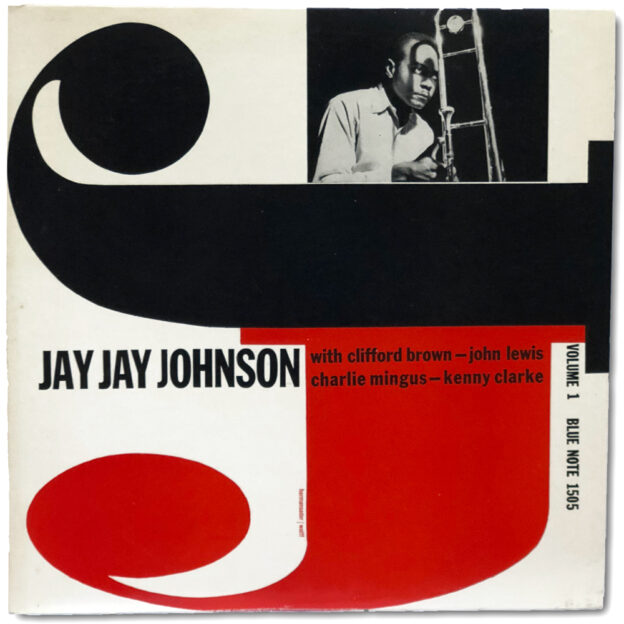

Lastly and aside from the phenomenal music laid to tape here, the thing I enjoy most about this LP is probably the cover. The color scheme of the bright red, black, and white pops out at one’s eyes, and the neatly placed photo of J.J., looking serious and a bit menacing, is fitting. It is a perfect example of all of the things that Blue Note covers were known for at the time: an excellent photograph juxtaposed with some of the most clever, aesthetically pleasing typography of the day. The cleanliness of this record, the jacket, and most importantly, the music makes me feel fortunate to have it in my collection.