For someone who grew up in the stereo age, mono recordings can sound primitive and cramped when compared to the wider, more spacious aspects of stereo sound, and this heightened sense of realism is what ultimately won over the music-buying public back in the 1960s. But not only are some of history’s greatest music performances only available to us as mono recordings today, time has proven that the antiquated format possesses an allure that continues to charm music lovers of all ages. When done right, mono recordings demonstrate a great sense of cohesion and power, and the best of them also do an ample job of establishing a sense of depth and space. Though creating a mono recording that checks all of these boxes is no small technological feat, the great audio engineers of yesteryear have managed to hand down to us a treasure trove of work in mono that is both breathtaking and timeless.

If you’re a vintage jazz record collector, you’re probably aware of the fact that all mono LPs are compatible with today’s stereo audio equipment. While this is true, playing a mono record on a stereo audio system without making the proper adjustments leaves room for improvement. This article is designed to help you get the most out of playing your mono LPs in a modern stereo world.

What Exactly Is a Mono Record?

The answer to this question is potentially quite complicated. The difference between mono recordings and mono masterings of recordings needs clarifying, as does the difference between mono records cut before and after the death of the mono format in the late 1960s. For the purpose of this article though we can settle for a simpler definition of a mono record being a record that is intended to produce the same exact audio signal (noise aside) in both the left and right channels of a stereo audio chain. True, without any fuss a listener will hear roughly the same thing coming from both speakers when they play a clean, new mono record on a stereo audio system (think reissues), but our goal is to hear the exact same thing from both speakers and in the process lower distortion and improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the overall listening experience. This goal becomes especially important when dealing with original pressings made in the 1950s and 1960s that have accumulated a significant amount of wear from usage.

Knowing If a Record Is Mono

Before we get started, let’s be sure that our records are even mono in the first place (by all means, if this is a no-brainer for you, feel free to skip this section). The easiest way to tell if a record is mono is if there is some indicator on either the front or back of the album jacket. For vintage records (we’re still talking ’50s and ’60s), the absence of the word “stereo” will usually suggest that a record is mono. The next easiest way to tell is simply by listening, and the best way to achieve this goal is with headphones. If all the music is more or less in the “center” of the stereo field while surface noise is clearly audible on the far left and far right of that spread, your record is mono. Note that the loudest parts of a worn mono record may distort “in stereo” so you need to focus on the quieter parts of the music. Finally, to state the obvious, if there are instruments or sounds distinctly positioned to either the left or right side of the stereo spread, your record is stereo. In cases where the stereo positioning of instruments is more extreme — common in our era of the ’50s and ’60s — you can also easily identify a stereo record by turning the panning knob on your amplifier all the way left then all the way right and back again. If some instruments sound very present at one turn then very distant or completely absent at another, then your record is stereo.

What’s Wrong with Listening to a Mono Record in Stereo?

If you’ve been listening to mono records in stereo your whole life, there are two significant ways in which your listening experience can be improved by effectively listening in mono on a stereo system. First, surface noise can be reduced and made less noticeable. Many marks on the surface of a vinyl record manifest as out-of-phase noise on the far left and right of the stereo field. When listening to a mono record on a stereo audio system, these pops and ticks are heard in a very different position than the actual music, which lies directly in the center of the stereo field. By listening in mono though, not only does the out-of-phase nature of this noise lead to its reduction in relation to the volume level of the music, much of whatever surface noise remains will be masked by the music in the center of the would-be stereo field.

Presented here are two audio clips. The first is of a mono record being played in stereo, the second being the same record played in mono. In the second clip, notice how the surface noise has collapsed to the center of the “stereo field” and is more difficult to discern once the music kicks in:

Horace Silver, “Finger Poppin'” (Original 1959 mono pressing of Finger Poppin’ with the Horace Silver Quintet)

Stereo Playback:

Mono Playback:

Second and similar to surface noise, groove wear on vintage mono records also often manifests as out-of-phase (stereo) noise. This distortion can also be reduced by listening in mono, and the fuzzy, smeared sound that would be heard listening in stereo becomes a tighter, more focused central image. The following audio clips emphasize this type of improvement:

Lou Donaldson, “Avalon” (Original 1962 mono pressing of Gravy Train)

Stereo Playback:

Mono Playback:

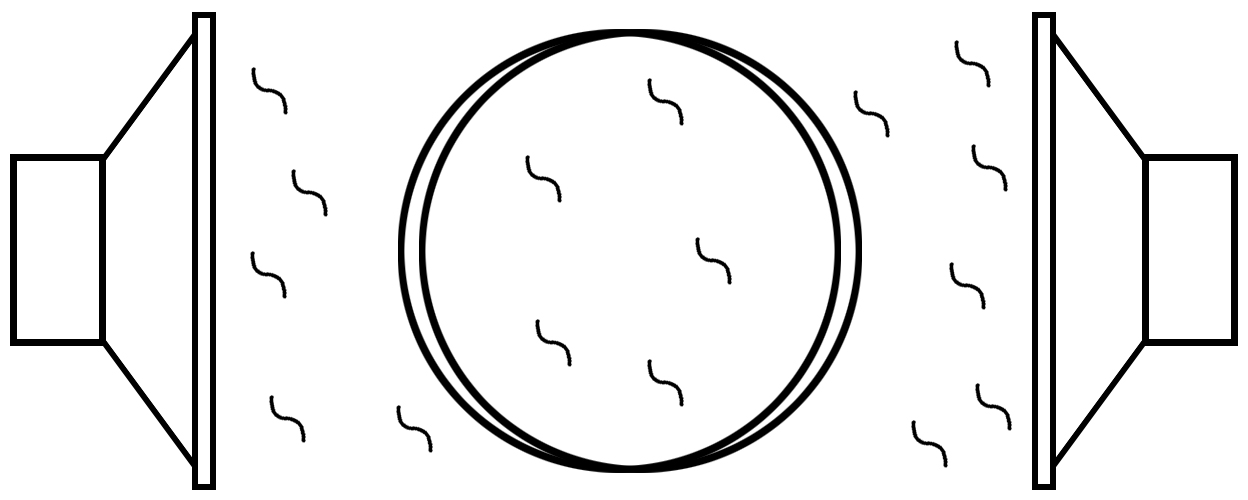

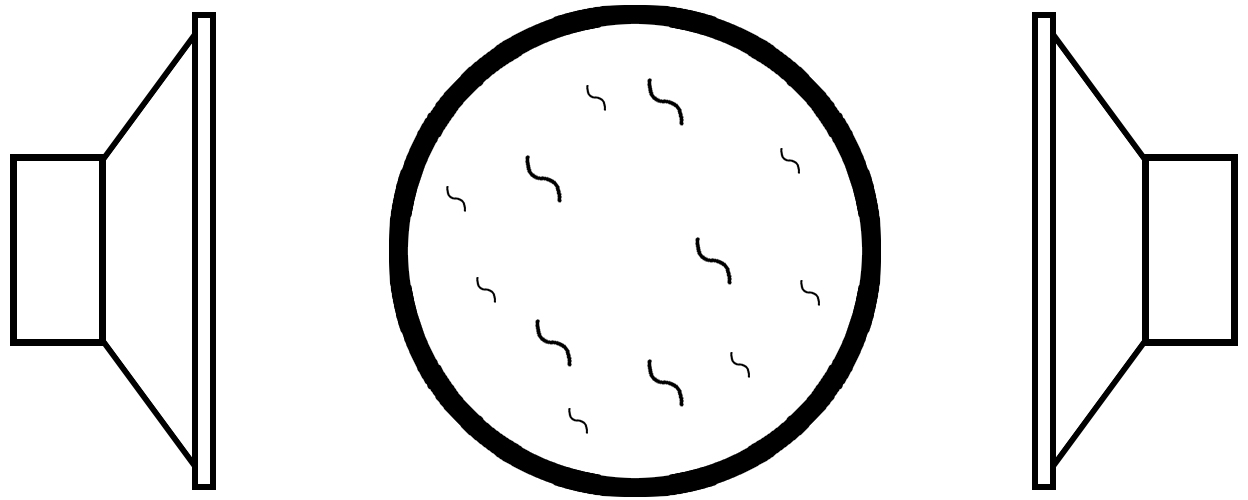

For a visual account of these improvements, the following two diagrams illustrate how listening to mono records in mono can provide an improved listening experience (the circles represent music and the curved lines represent surface noise):

Stereo playback of a mono vinyl LP

Mono playback of a mono vinyl LP

How Do I Play My Mono Records in Mono on a Stereo System?

Now that we’ve identified the ways in which playback of your mono LPs can be improved, how do we achieve this? Everyone has different equipment situations so there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but surely there is a sensible option for everyone.

If you use a turntable with a tonearm that accepts removable headshells, the most obvious hassle-free solution is to acquire a mono cartridge. Luckily, getting a mono cartridge doesn’t mean you need to hunt down and restore a vintage one. Cartridge manufacturers like Ortofon, Grado, Audio-Technica, and Miyajima all currently provide quality mono cartridge solutions that are compatible with modern stereo turntables.* You may need to adjust your counterweight each time you switch, but when you want to play a mono record, simply swap cartridges. (Click here to visit the Deep Groove Mono Cartridge Database.)

A sampling of mono cartridges currently on the market

If you don’t have a tonearm that uses removable headshells, or if you simply don’t want to fuss with swapping the cartridge and adjusting the counterweight every time, there are other options. While a mono cartridge will produce identical signals in both channels of a stereo system (a duplicated “mono signal”, if you will), simply summing the left and right channels of a stereo cartridge can actually produce comparable results (for more information, see the appendix at the end of this article).

One way to do this is with a mono button on an amplifier. Many vintage stereo amplifiers have mono buttons. If you don’t have access to one of these vintage amps, you can also sum with a stereo-mono switch, though these can be hard to find and are usually custom-built (members of the Steve Hoffman Forum can purchase one here). Another summing option is using a “double Y-cable” configuration, which involves placing a pair of RCA adapters in the signal chain, though the obvious drawback of this option is that you need to remove the adapters every time you switch between mono and stereo (the method is outlined here in this Steve Hoffman Music Forum thread).

Will either using a mono cartridge or summing provide more favorable results? Though the answer to this question certainly depends on which cartridges you are using, here we offer up one of these comparisons. The first is the result of playing a vintage mono record with a Grado MC+ mono cartridge and the second is a clip of the same record being played with a Shure M44-7 stereo cartridge and the mono button engaged on an integrated amplifier:

Johnny Coles, “Jano” (Original 1964 mono pressing of Little Johnny C.)

Grado MC+ mono cartridge:

Shure M44-7 stereo cartridge with channels summed:

A final, less popular option is to use a “left channel only” or “right channel only” setting on an amplifier. Unlike a mono setting that sums the channels, these settings will duplicate one of the two stereo channels in both signal paths. While this method typically fails to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the signal, it is preferable in some rare instances. For example, if a record was played many times on a turntable with severe anti-skate problems, one groove wall may be in much better shape than the other, and listening to one channel or the other may prove more desirable than summing.

McIntosh MA6200 integrated amplifier with mono, L-to-L&R, and R-to-L&R settings

Vintage vs. Modern Mono Records & Stylus Size: Is Bigger Always Better?

The only other variable that modern mono lovers need to consider is stylus size. Today’s stereo (and mono) LPs are cut with a groove width optimized for playback with a modern stylus tip measuring approximately 0.7 mils at its longest radius (1 mil equals 0.001 inches or one-thousandth of an inch; in the metric system, 0.7 mils is equivalent to about 18 “microns” or micrometers, where 1 micron equals 0.001 millimeters or one-millionth of a meter). However, vintage mono LPs mastered prior to 1970 were actually cut with the intention of being played back with a larger 1-mil (25-micron) stylus.

For mono LPs mastered after 1970, a 0.7-mil stylus is the only sensible option. Fortunately, this is the spec for virtually all modern cartridges, mono and stereo alike (a few exceptions to this rule are the Ortofon OM cartridge with optional D25M stylus, the Ortofon CG 25, and the Miyajima Zero, all which sport 1-mil styli). As for playback of vintage mono LPs mastered before 1970, while it’s true that these discs were cut to be played with a 1-mil stylus, a 0.7-mil stylus will also fit these grooves. What’s more, there’s an attractive theory that a narrower 0.7-mil profile might avoid areas of wear higher up on the groove wall created by repeated plays back when 1 mil was the standard. In a perfect world, collectors would have both options at their disposal and make their choices on a case-by-case basis. But in the event that you must choose one stylus for playback of all mono and stereo LPs from all eras, a 0.7-mil stylus should suit you just fine.

(L to R) Ortofon OM with D25M stylus, Ortofon CG 25, Miyajima Zero

Once more, we have two audio clips to offer up for comparison. The first is a vintage mono LP from 1959 being played with the previously mentioned Ortofon OM cartridge and D25M 1-mil conical stylus, and the second clip is the same record being played with a Shure M44-G cartridge with a 0.7-mil conical stylus (both cartridges are stereo and channels are summed for both clips):

Donald Byrd, “Lover, Come Back to Me” (Original 1959 mono pressing of Off to the Races)

Ortofon OM cartridge with D25M 1-mil stylus:

Shure M44-G cartridge with stock 0.7-mil stylus:

Note that stylus size in and of itself has no bearing on whether a record will play mono or stereo; the inner workings of the cartridge are what ultimately determine this.

Conclusion

Despite stereo’s current reign as the industry’s standard format, mono sound has certain qualities that distinguish it from stereo and make it special. When done right, mono can be a highly enjoyable listening experience. Mono recordings have a simplicity that give them character. Their “punch” is intrinsically tied to the limitations of the format, and the same can be said of the way the elements of a mono mix meld together into one cohesive whole. My hope is that this article has explained how to get the most out of your mono records and has also provided you with a practical, affordable solution in your quest to obtain the finest mono vinyl playback possible.

* Advanced collectors will appreciate a note regarding the difference between single-coil and dual-coil mono cartridge design. In theory, a single-coil design will provide an even higher signal-to-noise ratio than a dual-coil design. Known single-coil models include the Ortofon CG 25, Miyajima Zero, and Denon DL-102. Additionally, mono carts with no vertical compliance (the Zero and CG 25) may also produce superior results, though newcomers should be aware that the lower compliance of these cartridges requires a special high-mass tonearm to achieve the appropriate resonant frequency for the system.

Appendix

“Stereo information” in a stereo record is information that is not equally present in the left and right channels of a stereo signal, and it is determined by the unique vertical modulations cut into each groove wall. “Mono (centered) information” is equally present in both channels and is determined by horizontal modulations in the groove only. Since surface marks on a record generate both horizontal and vertical motions of a stylus, playing a mono record with a stereo cartridge will not only reproduce noise related to the vertical motions of the stylus, that noise will usually be more noticeable because it will be in a very different position than the music in the stereo field. Using a modern mono cartridge will certainly cure this ailment, but summing a stereo signal from a stereo cartridge will produce noticeable improvements as well. The reason for this is because much vertical noise in a record’s groove is “out-of-phase”, meaning that the voltages produced by the cartridge’s left and right channels are to some extent polar opposites of each other, so when they are summed together, not only is the volume of this (stereo) noise reduced, the relative volume of the mono information i.e. the music is slightly boosted as well.

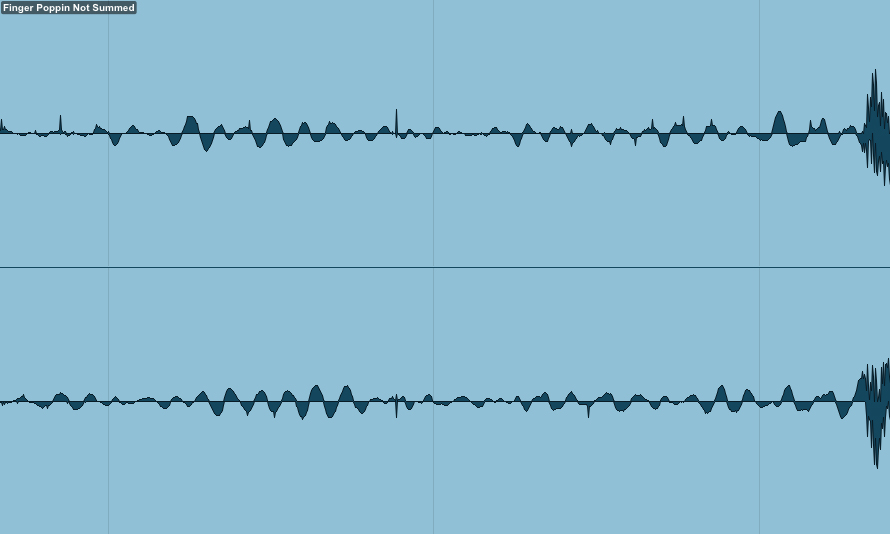

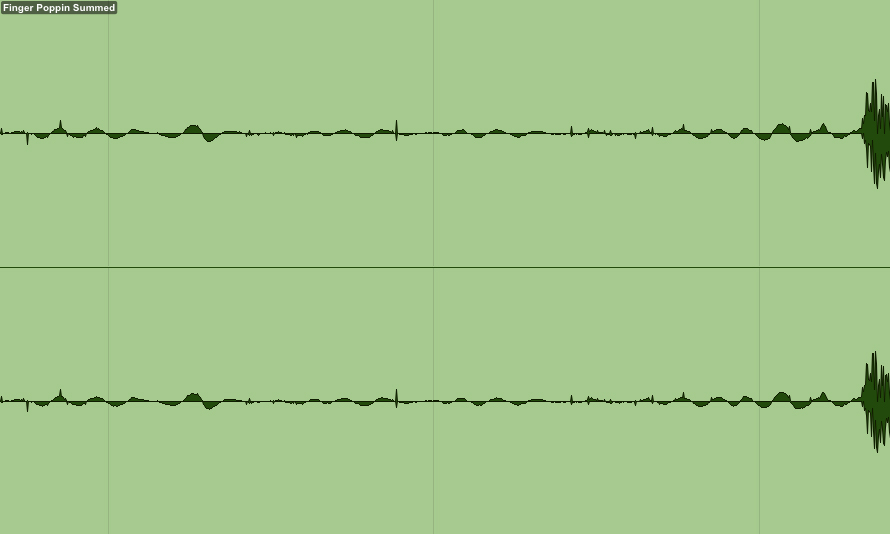

To illustrate this, the screenshots below show various waveforms in a digital audio workstation. The first shows the left and right channels of a mono record being played in stereo, while the second shows the same record played with the left and right channels summed using the mono button on an amplifier (both clips use the same stereo cartridge):

Lead-in groove of a mono record being played in stereo

Lead-in groove of the same mono record being played with channels summed to mono

Additional Resources:

(1) Deep Groove Mono Cartridge Database: Deep Groove Mono’s own database of mono cartridges currently on the market

(2) “Ortofon True Mono Cartridges”: Fantastic article on the Ortofon website discussing the history of monophonic playback

(3) “RCA Victor Announces Living Stereo”: 1958 short film explaining the science of stereo records (YouTube link)

(4) Stereo Cutting Head GIFs: Awesome GIFs explaining the science of stereo cutting heads, courtesy of VinylRecorder.com