- Original 1957 pressing

- “446 W. 50th ST., N.Y.C.” on both labels

- Deep groove on both sides

- “RVG” stamped in dead wax

Personnel:

- Teddy Charles, vibraphone

- Mal Waldron, piano

- Addison Farmer, bass

- Jerry Segal, drums

Recorded June 22 and June 28, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Selection: “Dear Elaine” (Waldron)

For Collectors

Prestige released numerous LPs in the late ’50s, many of which stand today as interesting mixes of rarity, low demand, and musical excellence. This album is one example of that. I first heard it on Spotify and instantly took to it, but the master tape had noticeably degraded by the time of its digital mastering. So it became a priority of mine to seek out an original. One weekend afternoon last winter I was checking out a Swedish jazz dealer’s website and there it was, an original pressing touting VG++ condition. The asking price was a tad high so I talked the seller down a little and about ten days later the LP arrived at my doorstep. Quiet vinyl is a must for quiet music like this, and as you will be able to hear in the clips above, this one’s definitely a keeper.

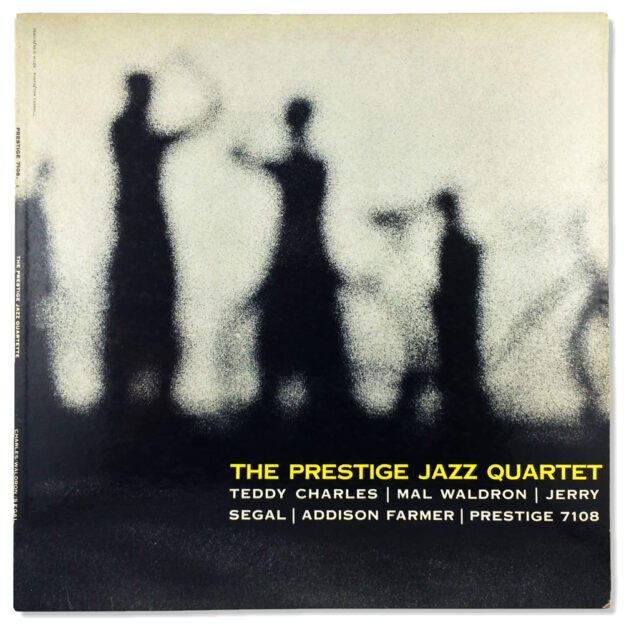

I was instantly a fan of the album art as well, which portrays a serene scene of silhouettes that to me appear to be practicing tai chi. What connection the cover is intended to have with the music I do not know, though I do find that its grey, clouded imagery complements the mood of the music quite well.

For Music Lovers

A pair of forward-thinking composers, Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron first recorded together in January 1956 for Atlantic Records release 1229, The Teddy Charles Tentet. A year later they collaborated on five albums in just as many months, four of which were recorded for Bob Weinstock’s Prestige and New Jazz labels (Olio, Prestige 7084; Coolin’, New Jazz 8216; Teo, Prestige 7104). The last album in the run is presented here, captured on two dates in late June 1957.

The soft timbres of The Prestige Jazz Quartet convey a calming mood throughout, even during the more uptempo moments. The album has experimental leanings that weren’t yet trendy in 1957, but the sparse solos hardly beg for the listener’s attention. The quartet arrangement with vibraphone makes for a spacious atmosphere that lends itself well to the nuances of the vibes. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder has also set the drums further back in the mix than usual, making even more room for the dreamy echoes of the vibes to resonate.

The program begins with a trio of movements penned by Charles (“Take Three Parts Jazz”), followed by a pair of Waldron compositions (“Meta-Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”) and concluding with a lesser-known Thelonious Monk tune, “Friday the Thirteenth”. “Route 4”, the first third of Charles’ piece, is an ode to the highway traveled by hundreds of the Big Apple’s finest jazz musicians traveling to and from Van Gelder’s home studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. The piece’s other bookend, “Father George”, refers to another passageway between the city and Van Gelder’s, the George Washington Bridge. “Lyriste”, the title of the middle section, is an invented word of Charles’ crafting that joins ‘lyrical’ and ‘triste’. In accordance with the titles, perhaps Charles intended the piece to serve as a soundtrack for a somber commute back to the island after a long day of recording, where use of the word ‘triste’ might have been meant to suggest that trips to Van Gelder’s were for many of the musicians a welcome break from the routine of city life.

Accompanying Charles and Waldron are bassist Addison Farmer (twin brother of trumpeter Art Farmer) and drummer Jerry Segal. Segal avoids complicating things by playing with tasteful restraint throughout, and Farmer more than plays his part by delivering an impressive solo on “Meta-Waltz”. Side B begins with “Dear Elaine”, an apprehensive sprinkling of notes that seems to provide a window into the mind of a cautious courter. Closing the album, Waldron’s regular use of refrain on “Friday the Thirteenth” creates a comforting sense of familiarity that culminates in an inspired hammering of adjacent keys. (In the original 1953 recording of the tune, Monk is in his prime, rightly delivering an astonishing solo, though there’s something about hearing that melody played on the vibes that makes more sense to me than hearing it on Rollins’ sax…what do you think?)

Charles and Waldron would collaborate sporadically moving forward, but this would be the last time the entire ensemble would be in a recording studio together. Despite it being a short-lived, lesser-known experiment, the Prestige Jazz Quartet was a group of exceptional talent that deserves its rightful place in the storybook of modern jazz.

Epilogue

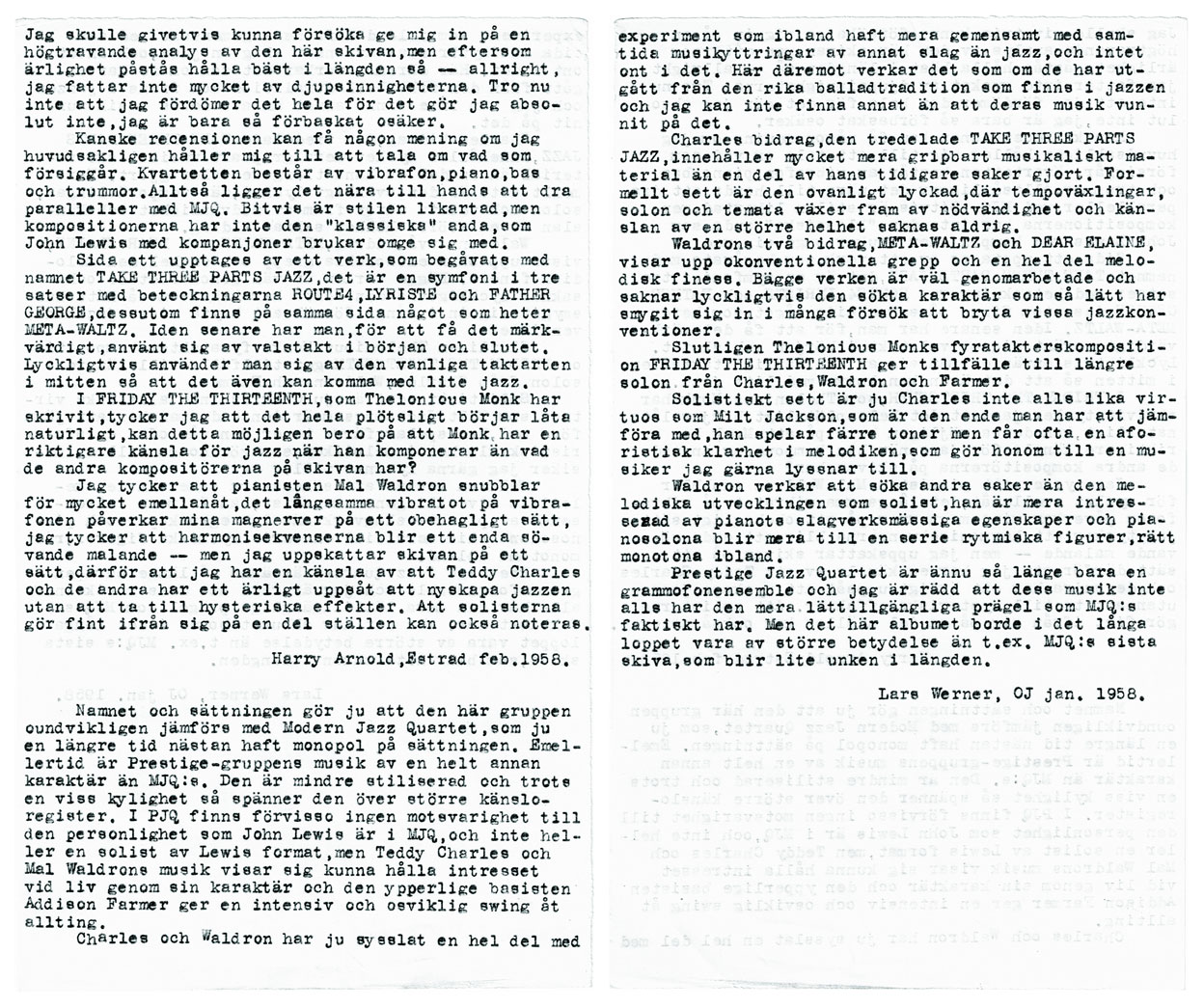

When I was preparing to take photos of the album jacket last week, I heard something jostling around inside, so I took a peek and to my surprise there was a small piece of paper inside with what appeared to be two interviews dated 1958 and typed in Swedish (the country the record came from upon my purchase). I then thought it would be cool to post a scan of the paper and maybe send out an S.O.S. for help translating it, then I thought of Google Translate and decided to do the translation myself, which I am presenting here.

The reviews would have originally been published in two Swedish magazines, Estrad (“Bandstand” in English) and OJ (“WOW”), and both were written by well-known Swedish jazz musicians: saxophonist/arranger Harry Arnold, whose resume included working with Quincy Jones, and pianist/composer Lars Werner. The original owner of the record must have been in the habit of typing up reviews for all the records they owned (perhaps to make up for the fact that they couldn’t read the English liner notes). Arnold seems the more opinionated of the two, possibly due to being more experienced and knowledgeable, though the way in which Werner has been charmed by the music resonates more with me. Through my amateur translation I also sense that Arnold’s review is surprisingly informal and that Werner was the better writer of the two (I also favored what I heard of Werner’s own music on YouTube).

For me, finding that piece of paper and reading the reviews felt like being transported back to the endlessly fascinating time that these records were made in, and I thought I’d share my experience with anyone who feels similarly nostalgic. I hope you enjoy!

Harry Arnold, Estrad (Bandstand), February 1958:

Harry Arnold

Of course I could try to make this into a pompous analysis of this record, but since it is said that honesty is best kept at a distance — all right, I do not have much profound to say about this record. Do not think that I condemn the whole thing because I absolutely do not; I’m just so damn precarious about it.

Perhaps the review will be more useful if I stick to the basics. The quartet consists of vibraphone, piano, bass, and drums, so it is tempting to draw parallels with the Modern Jazz Quartet. Here and there the style is similar, but the compositions are not in the “classical” spirit, as is usually the case with John Lewis and partners.

Side one is occupied by a work endowed “Take Three Parts Jazz”. It is a symphony in three movements with names “Route 4”, “Lyriste”, and “Father George”. In addition there is a song called “Meta-Waltz” on the same side.

On “Friday the Thirteenth”, which Thelonious Monk wrote, I think the whole thing suddenly begins to sound more natural, this may possibly be due to the fact that Monk has a truer sense of jazz when he composes than the other composers on the disc have?

I think pianist Mal Waldron stumbles too much at times, and the slow vibrato on the vibraphone affects my nerves in an unpleasant way. I think that the chord changes become one soporific grinding — but I appreciate the disc in a way, because I have a feeling Teddy Charles and the others have a bona fide interest in reinventing jazz without resorting to hysterical effects. It should also be noted that the solos are quite interesting at times.

Lars Werner, OJ (WOW), January 1958:

Lars Werner

In both name and composition, listeners will inevitably be tempted to compare this group with the Modern Jazz Quartet, which of course for a long time almost had a monopoly on sales in the vibraphone quartet market. However, the Prestige group’s music is of an entirely different character than MJQ’s: it is less stylized and lacks a certain coolness while spanning over a larger emotional register. There is certainly no equivalent in the Prestige Jazz Quartet to the personality that is John Lewis in MJQ, nor a soloist by Lewis’ standards, but Teddy Charles and Mal Waldron’s music proves capable of keeping the listener’s interest alive naturally, and the brilliant bassist Addison Farmer gives an intense and unfailing swing to everything.

To their credit, Charles and Waldron have been doing a lot of experimenting that sometimes has more in common with contemporary musical manifestations other than jazz. Here however, it seems that they have started from the rich ballad tradition found in jazz, and I feel they have found success with this approach.

Charles’ contribution, the tripartite “Take Three Parts Jazz”, contains much more tangible musical material than some of the earlier stuff he has done. The piece is highly successful, with tempo changes, solos, and themes emerging out of necessity, and the sense of a greater whole is never lacking.

Waldron’s two contributions, “Meta Waltz” and “Dear Elaine”, display an unconventional touch and much melodic finesse. Both works are well prepared, and fortunately they lack the sort of searching character that has so easily crept into many attempts to break jazz conventions.

Finally, Thelonious Monk’s four-beat composition “Friday the Thirteenth” provides an opportunity for longer solos from Charles, Waldron, and Farmer.

As a soloist, Charles is not as virtuosic as Milt Jackson — who is the only one he has to compare. Charles plays fewer notes but often gets an aphoristic clarity of melody, which makes him a musician I like to listen to.

Waldron seems to look for things other than melodic development as a soloist. He is more interested in piano percussion characteristics, and piano solos become more of a series of rhythmic figures, albeit rather monotonous at times.

The Prestige Jazz Quartet is still only a gramophone ensemble, and I am afraid that its music lacks the accessibility of MJQ. But this album should in the long run be of greater importance than, for example, MJQ’s last album, which gets a little stale after a while.