- United Artists mono reissue circa 1972-1975

- “A DIVISION OF UNITED ARTISTS RECORDS, INC.” on both labels

Personnel:

- Jerry Lloyd, trumpet

- Zoot Sims, tenor saxophone

- Jutta Hipp, piano

- Ahmed Abdul-Malik, bass

- Ed Thigpen, drums

Recorded July 28, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Originally released February 1957

Selections:

“Just Blues”

“Down Home”

For Collectors

This LP didn’t pique my interest until I saw an original pressing on the wall at an esteemed Manhattan record shop last fall. Though I was unfamiliar with the music, I knew of the record’s ‘holy grail’ status, and needless to say I was intrigued. At this point in my time collecting I felt confident handling such an expensive piece, and when I removed the vinyl from the sleeve it was beautiful — Lexington Ave. labels, flat edge, deep groove, all the trimmings. When I got home later that evening I gave it a listen on Spotify and quickly realized how fun and animated the music was. Though I had never spent anywhere near the asking price on a record before, the thought that I may never see the record again eventually captivated my mind, so I arranged an in-store audition.

I set out with cash in hand, ready to make what I believed to be a respectable offer. When I got to the store, I took a more careful look at the record before it played. Visually it was beautiful with only some light scuffing. When side 1 began, the music sounded loud and present and I liked what I heard. The second song, the ballad “Violets for Your Furs”, was quieter though, and revealed light yet consistent surface noise. The owner said the record had been cleaned, which was a bit disconcerting in consideration of the noise I was hearing. I began listening more carefully, and by the time the needle got to trumpeter Jerry Lloyd’s solo on “Down Home”, the last song on the first side, the deal was dead, as inner groove distortion was evident. I thanked the owner for his time and left the shop a (much) wealthier person.

At this point I knew I loved the music, so I picked up the Classic Records reissue. It sounded great, but I still wanted to see if there was something I was missing out on that could only be provided by a younger, fresher master tape. So I sought out the copy you see here, an early ‘70s United Artists copy (technically the second ever pressing of the album). Ultimately, the master tape sounded similar with both pressings and I decided to keep the UA.

Little is known about the origins of this batch of mono 1500-series reissues with classic blue-and-white labels. The covers of many of these turn up with cut corners, suggesting they were either intended for promotional use or eventually wound up in the discount bins of record stores. I’ve yet to see one of these with “Van Gelder” in the dead wax, which means these could be the first Blue Note reissues ever to not use the original master lacquer disks. There is also some speculation that these pressings were intended for the Japanese market. Perhaps the disks were manufactured in the US with AM Japanese radio in mind, and an even more extreme possibility is that the disks were actually mastered and manufactured in Japan.

But even if the disks were pressed here in the states it’s possible that some of these are not sourced from the original tapes. According to Blue Note archivist Michael Cuscuna, United Artists would have been the first parent label to demand that Blue Note’s original master tapes be duplicated (sometimes with Dolby noise reduction) in the event that the tape was beginning to flake. (This is why original copies of classic Blue Note albums with Van Gelder mastering are so valuable: there is no debating that they were made using first generation tapes shortly after the recording sessions.) But this myriad of possibilities doesn’t seem to have much of an effect on the quality of the finished product, the results of which can be heard in the needle drops above.

For Music Lovers

To stand out in the testosterone-overrun world of instrumental jazz, it certainly didn’t hurt that German-born pianist Jutta (pronounced “Yoo-ta”) Hipp was a woman. That’s probably what esteemed jazz critic Leonard Feather was thinking in 1954 when he began nurturing the undiscovered talent. After hearing a friend’s recording of her, Feather booked studio time in Germany for the 29-year-old redheaded bopper (New Faces – New Sounds from Germany, Blue Note 5056), then arranged for Hipp to come to New York City in November 1955 for a residency at the Hickory House on East 52nd Street. The six-month stretch that followed proved quite an eventful time for the pianist. She was recorded on location by Blue Note in April (Jutta Hipp at the Hickory House, BLP 1515/6), and amongst the plethora of world-renowned jazz musicians whose acquaintance she had the pleasure of making, Hipp was reunited with tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims, whom she had originally jammed with on the Continent a few years back when Sims was on tour with bandleader Stan Kenton.

Hipp woud eventually be asked to assemble a combo for a Blue Note session at the label’s holy house of sound, engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s home recording studio in Hackensack, New Jersey. Sims would be recruited along with drummer Ed Thigpen, the backbone of Hipp’s Hickory House trio. Trumpeter Jerry Lloyd came along with Sims and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik entered the equation as well. Overseen by Alfred Lion, a fellow German native, the session commenced in late July 1956 and produced the entirety of the LP in a single day.

The band warmed up with a pair of ballads: the Matt Dennis-Tom Adair composition “Violets for Your Furs” (first recorded by Frank Sinatra two years prior), and the standard “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)”. The former took what was perhaps a nervous Hipp four takes to get through, and while the time constraints of the LP format wouldn’t allow the latter on to the original release, it would surface for the first time 40 years later along with George Gershwin’s “’S Wonderful” on the 1996 Connoisseur Series compact disc.

|

| Sims and Hipp rehearsing at Van Gelder Studio |

Hours later, by the time seven songs were laid to tape, the session was all but complete when Sims would have suggested the band riff on an up-tempo twelve-bar progression of his choosing. The result was “Just Blues”, and the track proved to be so much fun that it would later be chosen as the album’s opener. (In a review for All About Jazz, critic Chris M. Slawecki quipped, “Sims contributed the opening “Just Blues”, although he apparently couldn’t be bothered to title it,” which provokes the comical image of Lion turning to Sims for the title after the take with Sims shrugging and humbly replying, “Just blues.”)

The album would eventually make it to store shelves seven months later in February 1957. But by this time Hipp had mysteriously disappeared from the scene, and without star power to drive album sales, the sides wouldn’t be repressed until the glory days of hard bop were long over, rendering the original LP a figment to the vast majority of the jazz record collecting populous.

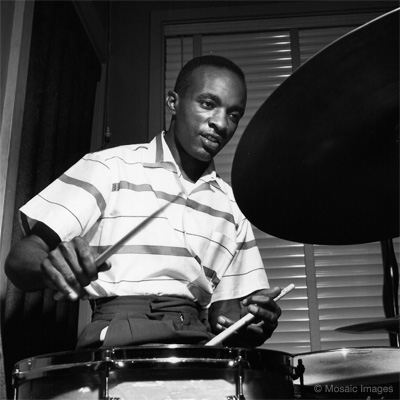

On first listen, the music here may sound a bit old-fashioned when held up to other cutting edge jazz albums recorded in 1956, but the consistently fun vibe of Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims proves difficult to deny. Sims would assume the unofficial role of leader that day, bringing a playful, infectious energy to the studio, and Hipp rose to the occasion despite known confidence issues. Thigpen, who would go on to form one-third of the legendary Oscar Peterson Trio, provides a steady, driving rhythm throughout, putting the soloists in the zone with inspiring momentum on more upbeat tunes like “Just Blues”, Lloyd’s “Down Home” and the J.J. Johnson composition “Wee Dot”.

|

| Drummer Ed Thigpen |

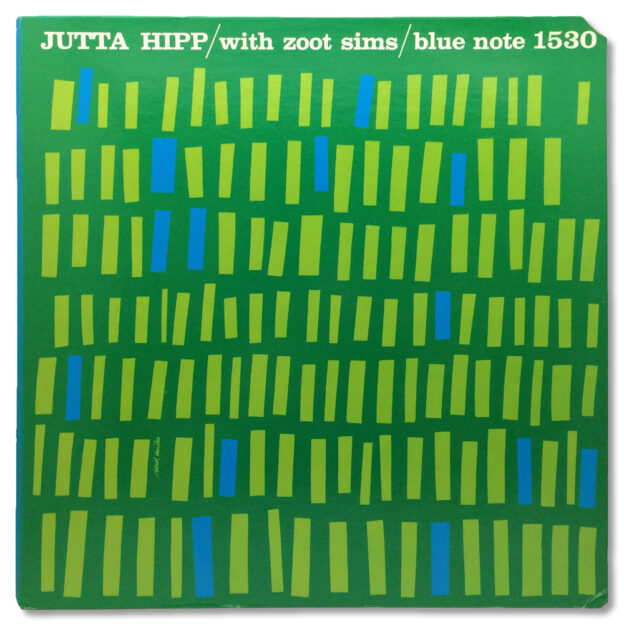

The recording itself is one of Rudy Van Gelder’s finest. By 1956 the engineer had finally backed off the quirky artificial spring reverb that hinders many of his earliest recordings, allowing listeners to hear the natural ambience of the Hackensack living room in all its makeshift glory. Soft, warm cymbals also define Van Gelder’s sound during this period, giving the music a unique, almost cartoony character. For the finishing touch, Reid Miles provided some of his most iconic design: a colorful, modern jumble of rectangles primitively imitating the keys of a piano (the cover has proven so iconic it has found a home in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City).

Sadly, this was the last time Hipp would enter a recording studio. At some point the pianist became jaded by the music industry, retreating to Queens to work in a textile factory. She returned to her first creative passion, painting, and lived alone there until 2003 when she passed away due to terminal illness. There are only a few recordings of the German phenom to be heard as a result, and we should be grateful for this particular shining example of her talents.